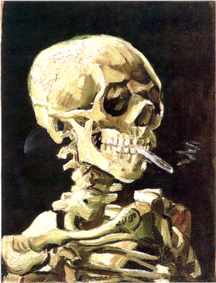

A. Cigarettes Kill At A Genocidal Rate. A cigarette-caused "annual death toll of some 27,500" was deemed a "holocaust" by the Royal College of Physicians, Smoking and Health Now (London: Pitman Medical and Scientific Pub Co, 1971), p 9.

A. Cigarettes Kill At A Genocidal Rate. A cigarette-caused "annual death toll of some 27,500" was deemed a "holocaust" by the Royal College of Physicians, Smoking and Health Now (London: Pitman Medical and Scientific Pub Co, 1971), p 9.

Cigarettes kill as a "natural and probable consequence" because, in the breathing zone, cigarette smoke contains vast quantities of poisons in excess of standard engineering maximum exposure limits on toxic substances. Such standard limits are typically promulgated by law (in the U.S. by 29 CFR § 1910.1000.) Rules define what is reasonable, notwithstanding some lay jury verdicts made in ignorance of said rule's legal definition of reasonableness.

For example, 29 CFR § 1910.1000 sets non-protracted carbon monoxide exposure at NTE 50 ppm average, whereas cigarette smoking involves repeated exposure to 500 - 1500 ppm. See G. H. Miller, "The filter cigarette controversy," 72 J Indiana St Med Assn (#12) 903-905 (Dec 1979), cited in L. J. Pletten [Letter], "Smoking as hazardous conduct," 86 New York St J Med (#9) 493 (Sep 1986). Cigarettes are like driving 500 - 1,500 mph in a 50 mph zone; it's easy to see why they kill people!

For prosecution purposes, the danger cigarettes pose as a "natural and probable consequence" is also evidenced by

(1) a vast body of laws premised upon the hazard, e.g., Michigan's decades old law stating that only safe cigarettes can be manufactured, given away, and sold, MCL § 750.27, MSA § 28.216, (2) our analysis of pertinent law, (3) our narrative on pertinent legal definitions, (4) U.S. regulations such as 21 CFR § 897 pursuant to analyses of the hazard and tobacco company conduct in 60 Federal Register 41313-41787 (11 Aug 1995) and 61 Fed Reg 44396-45318 (28 Aug 1996); (5) case law including State v Austin, 101 Tenn 563, 566-567; 48 SW 305, 306; 70 Am St Rep 703 (1898) aff'd 179 US 343 (1900); Grusendorf v City of Oklahoma City, 816 F2d 539, 543 (CA 10, 1987) (the Surgeon General warning label suffices to show "foreseeable" hazard); and (6) the many cases concerning injury from dangerous cigarettes due to their "ultrahazardous" nature and impact.

B. Gateway Drug To Other Drugs. Tobacco causes abulia and suffering leading to self-medication, thus is the gateway drug on which children are first hooked (average age 12). Alcohol follows, average age 12.6; then marijuana, average age 14. See DHEW NIDA Research Monograph 17, Foreword, p vi, supra; Fleming, R., Levanthal, H., Glynn, K., and Ershler, J. "The Role of Cigarettes in The Initiation And Progression Of Early Substance Use," 14 Addictive Behaviors pp 261-272 (1989); and. Department of Health and Human Services, Preventing Tobacco Use Among Young People: A Report of the Surgeon General (1994). Chapter 2 notes tobacco sellers' pattern of criminal lawlessness: "Illegal sales of tobacco products are common." After the gateway drug stage, other later stage drugs follow.

C. Alcoholism. Cigarettes' toxic chemicals cause abulia and suffering, thus self-medication via alcohol. "Smoking prevalence among active alcoholics approaches 90%." Source: Hayes, et al. "Alcoholism and Nicotine Dependence Treatment," 15 Journal of Addictive Diseases 135 (1996). (See standard medical references for why, medically, physiologically, this cause and effect relationship exists).

D. Crime. Cigarettes' toxic chemicals lead to abulia, then in turn foreseeably to crime.

"Nowhere is the practice of smoking more imbedded than in the nation's prisons and jails, where the proportion of smokers to nonsmokers is many times higher than that of society in general." Doughty v Board, 731 F Supp 423, 424 (D Col, 1989). "Nationwide, the [ratio] of smokers [to non-smokers] in prisons is 90 percent." McKinney v Anderson, 924 F2d 1500, 1507 n 21 (CA 9, 1991), affirmed and remanded, 509 US 25; 113 S Ct 2475; 125 L Ed 2d 22 (1993).

Tobacco's fatal effects are "natural and probable consequences." See standard legal references for definition of the terms "natural and probable consequence," an event happening "so frequently as [to be] expected [intended] to happen again, and "murder." See Black's Law Dictionary, 6th ed (St. Paul: West Pub Co, 1990), pages 1019 ("murder") and 1026 ("natural and probable consequence"). Instead of giving tobacco pushers the benefit of the doubt, pages 789-790 have the pertinent legal phrase, in odium spoliatoris omnia praesumuntur; every presumption is made against a wrongdoer.

A classic example of murder is killing people by poisoning them. Poisoning inherently involves a series of acts, i.e., involves deliberateness and premeditation, so constitutes first degree murder. Thus, the series of acts constituting tobacco exporting, which has as its "natural and probable consequence," genocidal numbers, millions, of killings, involves first degree murder.

Murder is of course illegal in all jurisdictions, for example, the United States and its law, 18 USC § 1111. There is a vast body of criminal case law against killing or poisoning people whether or not death immediately ensures. See, e.g., People v Carmichael, 5 Mich 10; 71 Am Dec 769 (1858); People v Stevenson, 416 Mich 383; 331 NW2d 143 (1982); and People v Kevorkian, 447 Mich 436; 527 NW2d 714 (1994).

The Carmichael case is especially apt as it bans providing a person a mind-altering drug impacting behavior. Tobacco is a classic mind-altering drug impacting behavior. Cigarettes' vast combination of poisons including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and rat poison, increase blood pressure, constrict blood vessels, make capillaries fragile, and inhibit clotting. (Think of a garden hose that has been (1) made leaky and (2) had pressure increased).

(1) addicts, (2) produces abulia, acalculia and destruction of the pertinent self-defense reflex, thus (3) protracts exposure to mass quantities of poisons.

Such basic criminal law precedents as People v Carmichael, 5 Mich 10, supra; People v Stevenson, 416 Mich 383, supra; and People v Kevorkian, 447 Mich 436, supra, establish the basis for prosecuting tobacco officials for deaths they cause.

Cigarettes emit vast quantities of carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide. Carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide are the gas chamber poisons that Nazis used to kill about six million people. Those genocidal officials (who killed far fewer than 37 million) were criminally prosecuted, and many executed. See The Nurnberg Trial, 6 FRD 69 (1946), The Genocide Treaty, Twentieth Century Examples of Genocide, and the Armenian Massacre Website. These other holocausts, even accepting their worst case allegations, have typically killed fewer people than does tobacco. Enforcing the laws referenced herein, which have no statute of limitations, would save many lives.

Pursuant to 18 USC § 3184

to Prosecute Cigarette Exporters

Causing Death in Target Countries

The prosecution process has certain steps: Foreign countries can issue arrest warrants for government and corporate officials involved in exporting tobacco, the gateway drug. Charges would include a count alleging that tobacco's "natural and probable consequences" are genocidal levels of death in targeted countries. The charged individuals are here in the U.S. where their crime planning process and series of acts to carry out the killings occurs.

Extradition of such accused individuals would utilize the procedures in U.S. law 18 USC § 3184. (Extraditing gateway drug [tobacco] exporters from the U.S. is a standard law enforcement action process. Activities in one country can violate laws of another country and/or international law, see, e.g., the cases of

- Augusto Pinochet (Chilean President captured in England on an arrest warrant from Spain [see pertinent legal brief, "The case of General Pinochet: Universal jurisdiction and the absence of immunity for crimes against humanity" (London, October 1998)]; and see background and impact by Sarah Anderson, "The Pinochet Precedent" (5 December 2006) and Tito Tricot, "Neither forgiveness nor oblivion: Chile: The Death of a Murderer" (11 December 2006)

- Slobodan Milosevic (Yugoslavian president arrested 31 March 2001 on a warrant from the Netherlands)

- United States v Noriega, 746 F Supp 1506-1541 (SD Fla, 1990), aff'd 117 F3d 1206-1222 (CA 11, 1997) reh en banc den 128 F3d 734 (CA 11, 1997) cert den 523 US 1060; 118 S Ct 1389; 140 L Ed 2d 648 (1998)

- Saddam Hussein (background by Anthony Dworkin, "Saddam in the 'Dock: The Options For A Future War Crimes Prosecution Of The Iraqi Dictator" (Thursday, 31 Oct 2002)). See also Helen Thomas, "Saddam Should Face International Court," Seattle Post-Intelligencer (19 Dec 2003)

- "Chile arrests scores over abuses" (May 2008) (A Chilean judge has ordered the arrest of almost 100 former soldiers and secret police over rights abuses dating from General Augusto Pinochet's government.")

- "Criminal convictions of 22 CIA agents in Italy" (Glenn Greenwald, 5 November 2009) (Covers "criminal conviction of 22 CIA agents (and 2 Italian intelligence officers) by an Italian court yesterday -- for the 2003 kidnapping of an Islamic cleric, Hassan Mustafa Osama Nasr, off the street in Italy and his "rendition" to Egypt to be tortured." U.S. criminals in high political positions "insist that the rule of law and accountability simply do not apply to our highest government officials when they break the law. Fortunately, other countries -- slowly and incrementally -- are rejecting that pernicious view.")

In World War II trials such as The Nurnberg Trial, 6 FRD 69, 161-163 (1946), prosecution included Julius Streicher and William Joyce, Nazi propagandists convicted and hanged for their pro-death media words. The Joyce transcript is in the book edited by J. W. Hall, M.A., B.C.L. (Oxon), Trial of William Joyce (London: William Hodge and Co, Ltd, Notable British Trials Series, 1946). So prosecutions for tobacco deaths must also include aiders and abettors in the media.

Once one successful prosecution occurs, there will likely be a series of criminal cases on government and corporate officials involved in exporting tobacco killing overseas' victims.

A similar culpability concept applies to private sector perpetrators, United States v Park, 421 US 658, 672; 95 S Ct 1903; 44 L Ed 2d 489 (1975) (holding private sector official, the company president, criminally liable for subordinates' acts). Related cases include United States v Y. Hata & Co, Ltd., 535 F2d 508 (CA 9, 1976) cert den 429 US 828; 97 S Ct 87; 50 L Ed 2d 92 (1976), and United States v Starr, 535 F 2d 512, especially 515 (CA 9, 1976). This applies rules of law making higher officials responsible, even corporate president, United States v Dotterweich, 320 US 277; 64 SCt 134; 88 LEd 48 (1943).

non-violent trickery, U.S. v Wilson, 721 F2d 967, 972 (CA 4, 1983); Frisbie v Collins, 342 US 519, 522; 72 S Ct 509, 511; 96 L Ed 541 (1952); and abduction without normal process of law, without invoking treaty provisos. References: Edmund S. McAlister, "Hydraulic Pressure of Vengeance: United States v Alvarez-Machain and The Case for a Justifiable Abduction," 43 DePaul Law Rev 449-522 (Winter 1994), citing the U.S. Supreme Court upholding abduction as distinct from extradition, United States v Alvarez-Machain, 504 US 655; 112 S Ct 2188; 119 L Ed 2d 441 (1992). That case followed an older precedent, Ker v Illinois, 119 US 436, 444; 7 S Ct 225, 229; 30 L Ed 421 (1886). "Granito: How to Nail a Dictator" (PBS, 28 June 2012) ("In January 2012, after 30 years of legal impunity, former Guatemalan general and dictator Efraín Ríos Montt found himself indicted by a Guatemalan court for crimes against humanity. Against all odds, he was charged with committing genocide in the 1980s.")

While U.S. and state law and case law warrant prosecuting tobacco officials with respect to the "natural and probable consequences" (millions of deaths) constituting murder that they are causing, such prosecutions are not occurring. See Pletten, [Letter], "Alternative Models," 87 Am J Pub Health 869-870 (May 1997), supra. This non-enforcement is due to certain U.S. political officials aiding and abetting the killings, obstructing justice. So many deaths constituting murder result. See, e.g.,

- Gordon L. Dillow, "Thank You For Not Smoking," 32 American Heritage 94-107 (February-March 1981), wherein p 103 discusses bribery of officials; and

- Cassandra Tate, "In the 1800's, antismoking was a burning issue," 20 Smithsonian 107-117 (July 1989), wherein p 115 likewise discusses bribery of officials.

Although both articles also contain pro-tobacco disinformation, thus enhancing the probative value of the admissions of widespread bribery, the criminal prosecution and conviction of a sheriff for taking bribes to not enforce another cigarette-related law is purely objective fact without pro-tobacco hype, United States v Sheriff Goins, 593 F2d 88 (CA 8, 1979).

U.S. government officials rarely prosecute each other for crimes. However, foreign governmental and judicial systems may not be so disdainful of the rule of law. It only takes one honest prosecutor in one nation to prosecute, one honest adjudicative body to convict. Once tobacco pushers are convicted and in prison (or executed, in death penalty countries), benefits are clear

(1) a halt to the many murders constituting genocidal levels of killings, saving lives not only in the U.S. but around the world. (2) prevention of all other tobacco effects, including but not limited to reducing the smoker population, the market for other abused drugs. Society will benefit from that and resultant reduced alcoholism and crime, and, of course, all other tobacco effects, examples at our homepage.

| Crime Prevention | Genocide | Government Confession | Government Crime | International Human Rights Law Context |

| Medical Statistics | Michigan Law | Prosecuting Non-Enforcers | Tobacco Murder | Toxic Chemicals |

| Discussion Group: More Participants Welcome |

This site is sponsored as a public service by

Please read our tobacco effects page. Copyright © 1997, 1999 TCPG

The Crime Prevention Group