| This is an online reprint of the book, The Use of Tobacco (1882), by Chemistry Professor John I. D. Hinds, Ph.D. To go to the "Table of Contents" immediately, click here.

Tobacco pushers and their accessories conceal the breadth of tobacco effects, the enormity of the tobacco holocaust, and the long record of documentation. The concealment process is called the "tobacco taboo." Other pertinent words are "censorship" and "disinformation." Here is the text by John I. D. Hinds, Ph.D. (1847-1921), Professor of Chemistry, Cumberland University, Lebanon, Tennessee, of an early exposé (1882) of tobacco dangers. It cites facts you don't normally ever see, including beyond mere personal health to national impact aspects, and Indians, data normally unreported due to the "tobacco taboo." Thereafter, in 1897, Tennessee banned cigarette sales. The phrase "tobacco taboo" is the term for the pro-tobacco censorship policy—to not report most facts about tobacco. As you will see, information about the tobacco danger was already being circulated in 1882, 82 years before the famous 1964 Surgeon General Report. Be prepared. |

|

by John I. D. Hinds, Ph.D. (Nashville, Tenn: Cumberland Presbyterian Publishing House, 1882) Go, little book, God send thee good passage, And specially let this be thy prayer, Unto them all that thee will read or hear, Where thou art wrong, after their help to call, Thee to correct in any part or all."—CHAUCER. -2- TO MY BELOVED MOTHER I DEDICATE THIS BOOK. -3- "Intuta quae indecora."—Taciti Historiæ, Lib. I. 33.

-4- PREFACE THIS volume is a revision and enlargement of two papers which appeared in the CUMBERLAND PRESBYTERIAN QUARTERLY, in the numbers for April and July of the present year. I have drawn freely from all the material within my reach, and I desire in this place to acknowledge my indebtedness to all those writers from whom I have quoted. I have tried to give due credit to every author, either in the text or by a foot-note. I send forth this little book with the full confidence in the justness of the cause which it represents, and with the hope that it may tend in some degree to check that senseless tobacco habit, which, if persisted in, will certainly bring degradation and degeneracy upon the American people.

CONTENTS I.—Introductory.

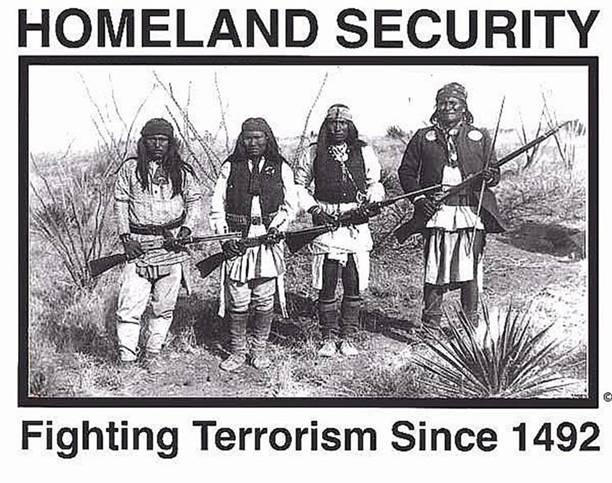

TOBACCO is more universally used among mankind than any other one thing except the most ordinary articles of food. It is estimated that nearly nine hundred million of the inhabitants of the globe are tobacco-users; while six hundred million use tea, four hundred million use opium, and only one hundred million use coffee. An article that holds subject nine-fourteenths of the human race is certainly worthy of attention. The tobacco habit is commonly regarded, even by those who are devoted to the weed, as useless, filthy, and expensive; and I have met with few persons who did not regret having formed it. This is particularly so in America, where people are unusually attentive to the promptings of conscience. The European uses tobacco, or drinks his wine and beer, scarcely asking the question of right and wrong. It gratifies an appetite and affords pleasure, and this is enough. In the United States the total abstainer is very common [Ed. Note: As reported earlier by J. B. Neil, 1 The Lancet (#1740) p 23 (3 Jan 1857)]; but to meet the German or Italian who does not smoke is an exception. Chewing, however—the worst way in which tobacco can be used—is rare except in America. The tobacco question is one of great interest to humanity; and the physician, the minister, the parent, and the teacher should all be alive to its importance. A simple statement of the facts in the case is sufficient, I think, to convince any thoughtful mind [Ed. Note: i.e., not smokers] of the great evils of this pernicious habit. If the following pages shall contribute, even in the least degree, to the cause of tobacco reform, I shall be content. Let the reader take the question to heart, and consider it most seriously. II.—DERIVATION OF THE WORD. The origin of the word tobacco is not very certainly known. It is most probably from the word tabaco, the name given by the Caribs to the pipe in which they smoked the leaves. Neander, one of the earliest writers on the subject, derived it from Tabaco or Tabasco, a province of Yucatan. It has been otherwise derived from Tobago, one of the Caribbean islands, and Tobasco, in the Gulf of Florida. III.—HISTORY. Tobacco is indigenous to America. When the crew of Columbus landed on the island of Cuba, in 1492, they found the natives smoking something which they afterwards found to be tobacco leaves rolled up in the leaves of maize, or Indian corn. It was also smoked in reeds, and the smoke was emitted from the nostrils as well as the mouth. It grew wild upon the continent, and its use seemed to be universal from Canada to the extreme South. The Mound-builder, the Aztec, and the Patagonian all smoked the weed.

The first detailed account of smoking among the Indians is given by [Fernández] Oviedo [1478-1557].† It was used by them to produce stupor and insensibility.

The smoke was taken

That the method of taking tobacco in powder was in vogue among the Indians, we are told by Roman Pane, who accompanied Columbus in his second voyage in 1494. He says "they take it through a cane half a cubit long. One end of this

†Historia General de las Indias [Toledo, Spain: R. de Petras, 1526]. they place in the nose and the other upon the powder, and so draw it up, which purges them very much." Thus we have found the origin of snuff and the cigar. The pipe was also used in South America* and Mexico, and elsewhere on the continent. When [Hernando] Cortez [1485-1547] made the conquest of Mexico in 1519, he found smoking to be a common custom.

That the mound-builders were inveterate smokers is shown

†[F. W.] Fairholt's Tobacco: Its History and Associations [London: Chapman and Hall, 1859]. by the great quantities of pipes found in the mounds. Many of the pipes from the old Indian graves are cut in the form of heads, with features of the Mongolian type, thus favoring the ethnological theory that America was originally peopled by tribes which migrated from Eastern Asia. Among the North American Indians smoking had rather a sacred character. The smoking of the Calumet, or pipe of peace, was indispensable to the conclusion of treaties, and the pipe was also used in the worship of the Great Spirit. The smoke of the sacred plant was considered a propitiatory offering, and the wild son of the forest hoped through it to win the favor of Him who ruled the storms and seasons. Catlin, in his Letters on tke North American Indians says:

-16-

We may also quote the following in this connection:

The American colonists adopted the habits of their wild brethren, and the cultivation of tobacco was one of their earliest occupations. Since then it has ever been one of the chief products of the States between parallels 35° and 40° north, and is cultivated from Canada to 40° south latitude, particularly in Mexico, Brazil, and the West India Islands. The exact time of the introduction of tobacco into Europe is not known. It is probable that it found its way into Spain, Portugal, France, Italy and England within one or two years time, Spain and Portugal no doubt receiving it first. Philip the Second of Spain [1556-1598] sent the Spanish physician Hernandez de Toledo to Mexico to study its natural products. On his return he presented some tobacco plants to the king. This was at least as early as 1560. In the year 1560 Jean Nicot, Lord of Villemain, French ambassador to Portugal, bought some seeds from a Flemish merchant who had brought them from Florida. Those he sent to the Grand Prior of France. Tobacco was hence called Herbe du Grand Prieur. On his return to France in 1561, he carried with him from Lisbon some of tlie plants, which he presented to the queen, Catharine de Medicis [1519-1589]. Thus it obtained the names Herbe de la Reine and Herbe Medicee. He also called the attention of scientific men to it, and introduced its use into fashionable society. Tobacco was introduced into Italy about the same time by Cardinal Prosper Santa Croce. He had also obtained it in Portugal, and it was named, in honor of him, Erba Santa Croce. The introduction of tobacco into England is variously attributed to Sir Francis Drake, Captain Richard Grenfield, Sir John Haw- kins, and Mr. Ralph Lane. The exact date cannot be stated, but it was perhaps known as early as 1560. The plant was certainly well-known as early as 1586. It was in this year that Sir Francis Drake brought some of the Indian pipes from America. Under the patronage of Sir Walter Raleigh smoking was introduced in the court, and soon became fashionable. The demand for it was so great that the sale of tobacco to England was one of the chief sources of wealth to the colonists of Virginia. This also laid the foundation for the tobacco industry of Virginia, which has always been characteristic of the State, and which unfortunately, too, has made large tracts of its land a barren waste. The use of tobacco in Asia before its introduction from America has been asserted, but it is highly improbable, as no mention is made of it in literature anterior to that time. The Orientals, no doubt, practised the burning of vegetable substances for incense, and for the purpose of inhaling the narcotic fumes, but there is no evidence that tobacco was in the list. Such practices are mentioned by Pliny [23 A.D. - 79 A.D.], Herodotus [485 B.C. - 428 B.C.], and Dioscorides. Tobacco was introduced from Europe into Turkey and Arabia about the beginning of the seventeenth century. It was first carried to Java in 1601, and to India in 1609. Tobacco is now cultivated in all parts of the world, and has everywhere escaped from cultivation. It may be found growing wild in the various parts of Europe and Asia, as well as America. I have frequently seen it in the forests of Arkansas and the Indian Territory. The countries in which it is grown are enumerated in Johnston's Chemistry of Common Life as follows:

Among narcotic plants, indeed, it occupies a similar place to that of the potato among food-plants. It is the most extensively cultivated, the most hardy, and the most tolerant of changes in temperature, altitude, and general climate. From the Equator to the fiftieth degree of latitude it may be raised without difficulty, though it grows best within thirty-five degrees of latitude on either side of the equator. The finest qualities are raised between the fifteenth degree of north latitude, that of the Philippines, and the thirty-fifth degree, that of Lattakia, in Syria. When once introduced, tobacco became very popular, and its use spread rapidly all over Europe, Asia, and Africa. The secret of its ready acceptance in France was, perhaps, found in the wonderful healing powers attributed to it. It was a panacea for all human ills. There was scarcely any disease for which it was not a remedy, and for many it was regarded as a certain cure. It was still cultivated in France as a medicinal herb long after smoking had become a popular dissipation in England. In England it was first received as a cure-all, but court patronage soon made its use fashionable and universal. The seventeenth century was the golden age of tobacco in England. It was the especial pride of the high and the low. Smoking was one of the necessary accomplishments of the gentleman. It was a reproach and a disgrace not to be able to smoke. Tobacco was not used then so much as now for its effect. It was more of a social habit, and for that reason, perhaps, men did not become such slaves to it as they do at the present day. Its praises were in everybody's mouth. Poets lauded it, and it found a prominent place in the literature and the pictures of that day. Indeed, a tobacco mania pervaded the whole realm. It was originally called drinking tobacco, and the smoke was emitted through the nose as well as the mouth. The ladies, too, were given to the practice, both in England and France. The practice of chewing tobacco was never popular in Europe. It was mostly confined to soldiers and sailors. About the time of the Restoration [1660], gentlemen were occasionally met with who were addicted to the habit. They carried a silver spit-box with them in the hand, and to discharge the golden juice with grace into this receptacle was considered a great accomplishment. We have already seen that the use of tobacco in powder originated with the Indians. The inhaling of powdered tobacco or snuff for medieval purposes was practised very early. It was recommended for all diseases of the head. [French Queen] Catherine de Medicis [1519-1589] is said to have first used it. She introduced it to the [Ed. Note: French court under King Henry II] court in 1562. While it was thus first used as a medicine, it soon became an article of luxury, and the practice spread over France, Spain, Italy, and England. In the seventeenth century there was a mania for snuff in France similar to that for smoking in England. In the court of [French King] Louis XIV. [1643-1715], jewelled snuff-boxes and highly scented snuffs were a part of the drawing-room toilet. A little later it became fashionable in England.

One of the earliest methods of making snuff was by grating the twisted tobacco. This was called tabac rape, and hence the name of the kind of snuff called rappee, which continues to enjoy popularity in Europe down to the present day.

Snuff-taking continued to increase in popularity in France until, in the latter part of the eighteenth century, it is said "there was no person in France, of whatever age, rank, or sex, that did not take snuff." The Germans followed closely in the footsteps of the French. One can scarcely recall the name of Frederick the Great [1740-1786] without thinking of his snuff-box. The Dutch and Scotch were scarcely less inveterate as snuff-takers, and the custom was found among all the Oriental nations. Am Irish clergyman of the eighteenth century is responsible for the following:

Lord Stanhope once estimated that two years of a snuff-taker's life was "dedicated to tickling his nose, and two more to blowing it;" and adds, "a proper application of the ume and money thus lost to the public might constitute a fund for the discharge of the national debt."

Tobacco lovers were not permitted to enjoy their habits unmolested. During the seventeenth century a most bitter and fanatical persecution was waged against tobacco. While the tobacco was, no doubt, at that time an unmitigated evil, the spirit of the persecution was [Ed. Note: counterproductive] such as rather to give it new importance than to cause its use to be discontinued. James I. of England wrote a Counterblasts to Tobacco in which there is much truth and at the same time much exaggeration and ill-temper. He characterizes smoking as a custom "Loathsome to the eye, harmful to the braine, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black, stinking fumes thereof nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless."The following will give a still better idea of the style of the royal anathemas: His Majesty said

His majesty further professed that were he to invite the devil to dinner, he should have three dishes; 1. A pig; 2. A pole of ling and mustard; and 3. A pipe of tobacco for digesture." James, however, did something which affected the tobacco user much more seriously than his Counterblaste. He raised the duty on tobacco from two pence per pound to six shillings and ten pence [Ed. Note: 82 pence total]. This made it an exceedingly expensive luxury. It is said that some of the gentry spent as much as $2,000 a year for tobacco.*

Pope Urban VIII. issued a bull [solemn papal letter] in 1625 excommunicating all persons who should use tobacco in any form in the churches, and in 1690 Pope Innocent XII. excommunicated all who should take "snuff or tobacco in St. Peter's at Rome." Its use was prohibited by royal decrees in Persia, Turkey, China, and Russia. The offenders were punished with amputation of the nose, various mutilations, scourgings, etc. The early colonists of New England made enactments against it, and particularly for-

bade its use on Sunday and during divine service. The strife ran very high. While some lauded it to the skies, others heaped upon it the bitterest curses. More than four hundred books are said to have been written against the use of tobacco, and, perhaps, as many in its favor. Persecution, however, in a matter of this kind is of no avail. Public sentiment, and a scientific demonstration of the ill effects of the use of tobacco, are the only things that can turn men away from it. A most important series of scientific investigations was made by prominent physicians of England about the year 1857, and their results were published in the London Lancet for that year. The most important of these results are embodied in the discussion of the physiological effects of tobacco further on. Much has recently been written against the use of tobacco, and many of the lead- ing men of the day are seriously considering the question as to whether the world would not be better off without it. Unfortunately, men grow fanatical, and cry out against it as a sin and a crime. Most of us have fathers and grandfathers who smoked and chewed all their lives, and yet were good Christians and robust, healthy men.

While the intemperate use of tobacco is certainly very injurious, the moderate use of it is rather a question of economy, propriety, and decency. But more of this hereafter. The tobacco plant belongs to the order Solanacece and the genus Nicotiana. The genus is named for Jean Nicot, mentioned above. Several species are cultivated, chiefly Nicotiana tabacum, which is the common Virginia tobacco. Nicotiana repanda and Nicotiana fruticosa are cultivated in the West Indies and tropical America. Nicotiana tabacum, Nicotiana macrophylla, and Nicotiana rustica are grown in Europe, the last chiefly in Germany, Russia, Sweden, and upon the shores of the Mediterranean. The common tobacco plant of the United States (N. tabacum) is an herbaceous annual with a large, viscid-pubescent, ovate-lanceolate, sessile, decurrent leaves. The larger leaves are near the ground (about 8 by 20 inches), and they decrease in size toward the top. The stem is unbranched and crowned with a loose panicle of rose-colored flowers, which have funnel-shaped corollas, and produce a two-celled capsule containing many black seeds. The leaf is green, ripening to a yellowish brown, and the plant grows four to six feet high. The order to which tobacco belongs has rather a bad reputation, as almost every genus contains poisonous plants, and they are generally unsightly, or have an unpleasant odor. Among the disreputable kindred of tobacco are night-shade (Solanum nigrum), horse-nettle (Solanum Carolinensis), Belladonna (Atropa Belladonna), henbane (Hyoscyamus niger), and Jimson weed (Datura Stramonium). The character of the order is somewhat relieved by the Irish potato (Solanum tuberosum), pepper (Capsicum annuum), tomato (Lycopersicum esculentum), and the night-blooming jessamine (Cestrum Parqui). Chemical analysis shows the tobacco leaf to contain an unusual number of constituents. Nicotine, nicotianine, and tobacco acid or malic acid are characteristic. Nitric, hydrochloric, sulphuric, phosphoric, citric, acetic, oxalic, pictic, and ulmic acids are also present. The quantity of mineral matter is large, amounting in some cases to 27 per cent. This is chiefly lime, potash, common salt, magnesia, and silica. The leaf also contains albumen, cellulose, gum, and resin.

Nicotine C10H14N2 is a colorless, oily liquid, with the odor of tobacco and an acrid taste. It has strong basic properties, forming crystalline salts with acids. It is soluble in water, alcohol, and ether, and on exposure to light becomes reddish-brown. It is a deadly poison, even in small doses, and in the minutest quantities causes convulsions and paralysis. It produces death more quickly than any other poison except Prussic acid. The quantity of nicotine in dried tobacco leaves varies from eight per cent. in the poorer qualities to less than two per cent. in the best Havana tobacco. Virginia tobacco has from six to seven per cent., and the tobacco of Europe from five to eight per cent. Since the physiological properties of tobacco are chiefly due to nicotine, the fine tobaccos are much less harmful than the poorer kinds.

Nicotianine, or tobacco camphor, is a fatty substance, obtained by distilling the leaves with water. It forms minute acicular crystals, and has a bitter taste and a tobacco-like odor. It is supposed to be identical with cumarin C9H6O2 found in the tonka bean and some other plants. It im- parts much of the flavor to tobacco, and the kinds which contain most of it are preferred. Nicotic, or tobacco acid, is characteristic, and has been found to be identical with malic acid. By dry distillation of tobacco a dark empyreumatic oil is obtained, which has the peculiar odor of old, foul pipe stems. It has a sharp, acrid taste, and is a violent poison.* It is a constituent of tobacco

-38- smoke. Zeise found the smoke of tobacco to contain, besides this empyreumatic oil, carbonic oxide, carbonous oxide, butyric acid, ammonia, paraffin, an empyreumatic resin, a hydrocarbon, and traces of acetic acid. ____________

VII.—PHYSIOLOGICAL ACTION. All animals are poisoned by nicotine. The fatal dose is extremely small. In experiments on rabbits it was found that a single drop would produce death in three and a half minutes. Its action is proportionately rapid in other animals. In fish and frogs its action is slow. Reptiles seem to be more easily affected by it. "Some tobacco juice thrown into the mouth of a black snake, six feet long, caused it to writhe spasmodically for a few moments and then become rigid, in which state it remained after death."The following are the results of the observations made by Melier upon dogs after the subcutaneous injection of nicotine in doses of from one to eight drops: The breathing was affected first, and became difficult and anxious. The pupils were dilated, and the animals staggered in walking. There was afterwards vomiting, and a discharge of ropy mucus from the mouth. Then followed trembling, convulsions, complete exhaustion, paralysis, and death. (Stille.) Its action has been more carefully studied by Kolliker, Van Praag, and others, and may be summed up thus: "Nicotine primarily lowers the circulation, quickens the respiration, and excites the muscular system, but its ultimate effect is general exhaustion, both of animal and organic life."The effects of nicotine upon man have been determined by careful experiments. The following are the observations made by Schroff upon two men to whom he administered nicotine in doses of from 1/32 to 1/16 of a grain: Even the minutest doses occasioned a burning sensation in the tongue, a hot, acrid irritation in the fauces, and when larger quantities were taken, the entire length of the œsphagus felt as if it had been scraped with an iron instrument. Salivation was abundant. A sense of heat diffused itself to the chest, head, and finger tips, accompanied by general excitement. In larger doses the brain was more affected, and there was heaviness, torpor, sleepiness, indistinct vision, imperfect hearing, dryness of the threat, and labored respiration. In forty minutes a sense of unwonted debility and weakness was perceived, the head could scarcely be held erect, the face was pale, the features relaxed, the extremities became as cold as ice, and the coldness gradually advanced towards the trunk. Faintness ensued with coming insensibility and loss of consciousness. One of the experimenters was attacked in the first half of the second hour with peculiar clonic spasms of the whole body, which increased in violence during forty minutes, and lasted an hour. The spasms began by a tremulous movement of the limbs, and gradually involved the whole muscular system, chiefly affecting the muscles of respiration. This act was oppressed and short, every respiratory movement being composed of a number of short and incomplete inspirations. The other experimenter was effected at this period with unusual muscular debility, very laborious respiration, and a rigor. In other respects his symptoms were the same. Both persons, on their return home, felt extremely weak and chilly, and walked with ill-assured steps. One of them had a return of the spasms. The following night both were restless and sleepless, and the next day were unwell, tired, sleepy, and without appetite. Three days elapsed before the effects were entirely dissipated. (Stille.)

Nicotine is one of the most violent of poisons. When given in sufficient quantity it produces death in man in from two to five minutes. The symptoms of tobacco poisoning are the same as those of nicotine, except that the intensity is diminished. These symptoms always ensue when one not accustomed to tobacco takes it in any form. They are seen in persons just beginning to chew or smoke. Habit inures the system to it so that large quantities may be used without momentary inconvenience, and in this case its effects are manifested in constitutional disorders. The poisonous dose cannot be defined. This depends upon the susceptibility of the individual. Poisoning may follow its introduction into the stomach or its external application, and if a sufficient quantity gets into the system death is always the result. There is no antidote, and the only hope of recovery from the poison lies in emetics, heat, friction, artificial respiration, etc. An overdose of tobacco causes nausea, malaise, giddiness, vomiting, colic, diarrhœa, coldness of the limbs, clonic spasms, utter prostration, and, if the dose is sufficient, death. Alarming symptoms sometimes follow the mere inhalation of the emenation from tobacco, and several cases of death are reported from this cause. Serious and sometimes fatal results follow the swallowing of tobacco or tobacco juice, even by those accustomed to its use. A case is told of a young man who swallowed a piece of crude tobacco. "He became suddenly insensible, motionless, and relaxed, with contracted pupils and a scarcely perceptible pulse. There succeeded convulsions, loud cries, vomiting, and death by syncope or exhaustion." Similar effects sometimes follow immoderate smoking.

All the symptoms of tobacco poisoning are produced by the external application of tobacco and its preparations. Moist leaves applied to the tender parts of the body produce vomiting and exhaustion. The application of the oil from a tobacco pipe to a ringworm on a child caused the usual effects, and made the child feeble and sickly for five years thereafter.

Tobacco is an excellent remedial agent, but owing to the uncertainty of its action, and the distressing and sometimes fatal consequences of its administration, it has not been much used as a medicine. It is particularly useful as a nervous sedative. It is also used in diseases of the digestive system, pulmonary affections, dropsy, etc. It is applied externally in the treatment of skin diseases, gout, articular rheumatism, and nasal polypus. It has been used in cholera morbus and lead colic, and is said to be a certain antidote in poisoning by mushrooms. The seeds are sown in March in beds specially prepared, and in April or May the plants are transferred to the fields and planted in rows two or three feet apart. They are cultivated with the plough and hoe. The leaf being the useful part, care is taken to concentrate there as much of the strength of the plant as possible. In order to attain this object, when ten or twelve leaves are formed the plant is topped to prevent flowering and seeding. All lateral shoots and suckers are carefully removed. When mature, the plants are cut and cured and prepared for shipment. In the curing process the leaves are piled in heaps and caused to undergo a sort of fermentation. By this means the albuminous matters are destroyed, the amount of nicotine made less, and aromatic substances produced. The cultivation of tobacco is not much favored by the best farmers, as it is very exhausting of the soil. The great amount of mineral matter it removes causes the land to wear out very rapidly. The tobacco leaf, when burned, gives from 11 to 28 per cent. of ash. Then there is a large amount of nitrogen in the nicotine, nitre, and albumine of the leaves. All these must come from the soil. The quantity of matter removed from the soil by a ton of tobacco is about fourteen times as great as the quantity removed by an equal weight of the grains of wheat. Tobacco land, therefore, unless carefully rested and fertilized, soon wears out [Ed. Note: as in Virginia, p 20, supra]. Tobacco is cultivated nowhere so extensively as in the United States. Most countries scarcely produce enough for home consumption, while the United States exports the greater part of its yield and supplies half the world. The average crop may be taken at 450,000,000 pounds, 250,000,000 of which are sent to foreign countries, chiefly England and Germany. More than one-third of the export goes to Bremen [Germany]. Liverpool is the next greatest market. Next to the United States, Cuba grows the most tobacco. Its annual yield is about 60,000,000 pounds. Austria produces about 45,000,000 pounds, and France 20,000,000 pounds. Its cultivation is prohibited in England. Tobacco is taxed heavily in all countries, and thus becomes a source of great government revenue [Ed. Note: but far below its damaging cost to society]. Its cultivation is prohibited in England in order to increase the imposts. The annual receipts of the United States from duties on tohacco is [1882] near $35,000,000. That of England is about $40,000,000. Tobacco is a monopoly in France, and the government profit is some $60,000,000. The duties in Austria amount to $40,000,000. Notwithstanding this great revenue, it is doubtful whether tobacco is of real profit to a nation, since it takes the people's money without returning a just equivalent. A country, as a whole, is benefitted only by that which brings real good to its citizens. The forms in which tobacco is prepared for use are chewing tobacco, smoking tobacco, cigars and snuff. Chewing tobacco is made from leaves of an ordinary or inferior quality by pressing, twisting, or cutting. Liquorice, syrups, and various flavoring matters are used, and sometimes leaves of other plants are mixed in. To make what is called "fine-cut," leaves of the best quality are cut by machinery mto fine shreds. The common smoking tobacco is made from fragments of leaves and stems, and is frequently adulterated [Ed. Note, details, Chapter XII]. The greater amount of tobacco is consumed [1882] in the form of cigars. The best cigars come from Havana, partly because the tobacco is of a superior quality, and partly because the Cubans are more skillful in the manufacture. While the American adheres to his pipe, the cigar is of almost exclusive use among the better classes in Europe. The cigarette is quite popular now. It is prepared by the smoker for immediate use by rolling up finely cut tobacco in thin pieces of paper. Snuff is prepared by grinding the tobacco in mills. It has been used since tobacco has been known, and is applied to the nose. Ammoniacal and lead salts and aromatic substances are added, and it is to these and the free nicotine present that snuff owes its irritant action upon the mucous membrane of the nose. The use of snuff in England and France after its introduction became almost universal, but is now on the decline. There is another method of snuff-taking which seems to be peculiar to the Southern United States. It is in vogue among the women of the lower classes and the negroes, and has unfortunately found acceptance with some of the best women of the South. There is a strong public sentiment against it, however, to which it must eventually yield. The snuff is applied to the tongue with a little spoon, hence the name "dipping.'' A wooden or bark brush is however more frequently used instead of the spoon. Adulterations of tobacco are very common, particularly in those countries where the duties are high. Some of the substances used as adulterations are harmless, while many add much to the injurious effects of the tobacco. Some are added merely to gratify the taste of the buyer. Saccharine matters are most used, such as sugar, molasses, treacle, and liguorice. Dextrine, gum, saltpetre, green vitriol, common salt, sal ammoniac, yellow ocre, resin, sand, dyewoods, fustic, peat, red lead, starch, bark, meal, and other substances are added to give pungency and add weight. The leaves of other plants are frequently mixed with the tobacco leaves. Those most used are the leaves of beet, rhubarb, cabbage, dock, burdock, and colt's foot. Mosses, bran, malt-combs and terra japonica are sometimes added. Other plants possessing narcotic properties are used in various countries as a substitute for tobacco, or as an adulteration. The following is from Johnston's Chemistry of Life;

A word may be said in this connection in regard to the flavors of different kinds of tobacco. These depend upon the climate, soil, method of culture, manner of curing and manufacturing, age, and also upon the manure used in fertilizing the land upon which it is grown. The characteristic substances of the dried tobacco leaf are volatile and gradually escape. Thus, as manufactured tobacco and cigars grow older, they become less active and more delicate in flavor. The more delicate flavors depend upon the nature of the soil and the kind of fertilizer used.

Let the smoker think of this when he is enjoying the delicate flavor of his fine cigar.

"RAUCH—RAUCH—IMMER RAUCH!" The practice of chewing tobacco is nowhere so prevalent as in the United States. The American is omnivorous, and, therefore, must eat tobacco as well as other things. Not satisfied with this, he must also smoke, snuff, and dip, and occasionally one is found who indulges the practice of thrusting the "quid" in the nostrils. The man who is able smokes fine cigars, the poorer man smokes the pipe for economy, and as that is not always conhe often chews instead. The old too, smokes her pipe and the ladies assemble around a huge spittoon and have a social "dip." Chew- ing is more common in the South and West, while smoking prevails in the North and East. Smoking is much more practiced than chewing, and will survive it many decades. It has the advantage of being more respectable, more decent, and less injurious. It has a strong hold upon the American people, and will long retain its power. Be it said to the credit of this people, however, that there are many who do not use tobacco at all. There is a large anti-tobacco element, which is constantly gaining strength. Reform must be slow, since men are loth to leave a habit once contracted. It must be hoped for only in the next generation. We are much encouraged in this hope by the fact that many young men are now taking steps in the direction of total abstinence from tobacco. The sentiment has grown so strong in some of our colleges and theological schools that the practice is regarded as rather disgraceful. This is a healthy sentiment, and I am glad to see that young preachers are active in this matter. It is useless to fight against a habit as long as the bearers of the banner of the Cross are its slaves. If any profession should be pure, it is the ministry. Notwithstanding all that may be said to the contrary, it is a certain fact that the use of tobacco by a minister of the gospel is always the occasion of remark, and is in a degree prejudicial to his influence. This consideration alone, if there were no other, should persuade him to renounce the unclean thing. A common apology of mankind is, "I see no harm in it." A far nobler thought is, "Do others see harm in it?" This is what Paul meant when he said, "Wherefore if meat make my brother to offend, I will eat no more flesh while the world standeth."—1 Cor. VIII.13. So common is the custom of chewing tobacco in the United States [1882] that the spittoon is a piece of furniture scarcely less requisite than the chair or the water bucket. No house is complete without it. In the court-room, in the assembly hall, in the office, by the domestic hearth, and in the parlor, we always find this ubiquitous little article; and like an angry skunk, whenever disturbed it sends forth stifling odoys, suggestive of the slaughter pen and the charnel house. The mixed crowds that assemble in the legislative halls at Washing- ton may be taken as fairly representative of the conditions of things in the States from which they come. There chewing and spitting are in their glory. The first legitimate conclusion that one can come to in passing his eye over the assembled congress, is that those honorable gentlemen had met for the serious purpose of chewing their quids and filling the public spittoons. This would not be so bad if the spittoon was always the recipient of the contents of those capacious mouths. But such is not the case. The carpets, the floors, the seats and the desks all receive their share, and one can neither walk nor sit without becoming besmeared with the amber fluid. [Charles] Dickens [1812-1870], in his American Notes [London: Chapman and Hall, 1842)], calls Washington the "headquarters of tobacco-tinctured saliva," and in speaking of the Senate seriously recommends happen to drop any thing, though it be their purse, not to pick it up with an ungloved hand on any account." This is certainly a poor improvement upon the snuff-taking mania of the days of Henry Clay [1777-1852]. If tobacco could be entirely cleaned out of the capitol at Washington, those august bodies that assemble there, together with the nation which they represent, would rise one hundred per cent. in the estimation of foreign countries, and in their own self respect. The lawyer and the politician seem more devoted to tobacco than any other class of men; and this accounts, perhaps, for the bloom and luxuriance of the practice in our capitol city. The sour smell of old tobacco juice is eminently characteristic of the court-house, and the lawyer's office-stove whose base is not loaded with defunct quids is an anomaly which has never come under my observation. In Europe smoking is almost universal, but the tobacco chewer is seldom met with except among sailors. The average European would be thoroughly disgusted with this decidedly American way of using tobacco. But the curling smoke of the cigar is his great delight. From the time one lands upon the Continent until he sets sail again, he is hardly out of an atmosphere of tobacco smoke. The German is the prince of European smokers. The Irishman smokes not less perhaps, but with him it becomes a necessary sensual gratification, while with the German it is a luxury, an accomplishment, a pleasure and a duty. He smokes all the time and everywhere [often, American tobacco]. At home, at the table, on the street, in the parlor, in the concert hall, in the railroad coach; indeed, there is scarcely any place where the savory fumes of the beloved weed may not be met. In Germany there are no smoking-cars and no smoking-rooms. Occasionally one can find a car (Nichtraucher) where smoking is not allowed, but even these are often filled with fumes of tobacco. During a six-months residence at Berlin, I met with but one German who did not smoke. According to the law of association of ideas, the words German, tobacco and beer mutually suggest each other.

In Germany the women do not use tobacco. The man claims the right to do all the smoking, and considers that if he divides his glass of beer with his wife, he has discharged his whole duty. If there is any thing he is faithful to, it is his pipe and cigar. His beloved beer glass must be left at home, but not so his cigar. He makes it a point to smoke all day long, not even stopping at his meals. He carries his cigar to the table and smokes between dishes, and frequently alternates whiffs of smoke with mouthfuls of food. It is his delight to sit by you and puff clouds of smoke directly in your face, and that, too, regardless of your sex. However crowded a room may be all day long, a restaurant, for instance, it never occurs to him to replace the fumes by fresh air. The concert halls are furnished with chairs and tables, and while the audience is being regaled with choice selections from Mozart, Strauss, Flotow and others, especially noisy, boisterous, thundering Wagner, each indi- vidual is assiduously following his favorite occupation. The men smoke, the women knit, and both drink beer, while the utmost seriousness pervades the whole assembly. Enjoying one's self is a matter of business among these people, and seeking amusement is regarded a duty irrespective of one's inclinations. If you do not want to smoke, you must do so anyhow, for that is, by common consent, considered one of the highest sources of enjoyment, and you would be doing yourself the greatest injustice to so deny yourself. To refuse a cigar or a glass of beer is a breach of etiquette which is unpardonable, and at the same time is a violation of one of the first laws of German being—one must have amusement (vergnügung). The German, however, has one redeeming trait. He does not chew. He is too decent for that. But smoking is an evi- dence of good breeding. A man promenading in the parks and beer gardens on a Sunday afternoon without a cigar either in his mouth, hand or pocket, would feel himself utterly disgraced. The pipe in such a place would be very plebeian. This should be confined within the sacred precincts of home. The pipe at home for economy, the cigar on the street and in society for respectability—this is the code. Such is the intemperance in the use of tobacco that the physicians frequently have to make it the subject of discipline in the treatment of their patients. The evil effects of it would be much greater were it not for the fact that young boys do not smoke. The cigar and the "stove-pipe" are contemporaneously assumed. Americans might learn a valuable lesson from this example. It is useless to talk now to the German about quitting tobacco. He is so wedded to the weed that he will have to undergo a complete social and physical regeneration before reform will be possible. Tobacco reform in America has a bright future, but in Germany it is a forlorn hope.

Next to the German, perhaps, is the Italian in point of this accomplishment, and the peasants of the Tyrol are seldom seen without the pipe. I think if a line be drawn from Berlin to Rome it may be taken as the line of maximum use. East and West of this line the amount of tobacco consumed gradually diminishes, with local exaggerations occasionally, as in Spain and Ireland. Paddy and his clay pipe are inseparable, and the women smoke in Spain as well as the men. In England and France the cigar is a necessary accomplishment, and snuff still holds its sway. Russia follows close behind, and the cigarette is quite popular long the ladies there. It is in Asia, however, that the greatest quantity of tobacco is used. The people of Turkey, Persia, India, and China all smoke without respect to class, sex, or age. In Burmah the children smoke in the mother's arms. Tobacco has not only kept pace with civilization but has far out-traveled it, and may to-day be found in every nook and corner of the habitable globe. "A pipe! a pipe! My heart's blood for a pipe! From its earliest history, the pipe has been associated with tobacco. The first forms were very much like the little clay pipes common now in Ireland. In the ancient pipes the cavity in the bowl was always very small, showing that very little tobacco was smoked at a time. This was, perhaps, partly due to its costliness. It must also be remembered that it was formerly customary to pass the pipe from mouth to mouth, however large the company. These little pipes were called "fairy pipes" or "elfin pipes." Pipes are found in great quantities in the Indian mounds of America, about the old Mexican ruins, at London, and on the Continent generally. This fact alone, had we no history, would show how universal has been the practice of smoking since it was introduced. The pipe consists essentially of a bowl to hold the tobacco and a stem through which to draw the smoke into the mouth. A secondary bowl is sometime added as a receptacle for the poisonous oil which collects in the stem and is liable to be drawn into the mouth. The excellence of the meerschaum pipe depends upon the facility with which it absorbs this oil. The pipe is thus darkened, and to get a rich uniform brown tint is considered a great feat. "There is a legend of one who determined to have a perfect meerschaum, and it must be understood that perfection cannot be attained if the pipe once lighted be allowed to cool; so an arrangement was made that it should pass from mouth to mouth of a regiment of soldiers, the owner of the pipe paying the bill. After seven months a most perfect pipe was handed to the 'fortunate' proprietor, with a bill for more than one hundred pounds sterling, which had been the cost of the tobacco sacrificed in the feat."*In the Eastern pipe, called the hookah, the smoke is thoroughly cooled by being drawn through water, arid afterwards through a long stem, and is thus deprived of much of the injurious matter. It requires considerable force to draw the smoke through the water and thus this pipe is said to be injurious to the lungs. Tobacco pipes have been the subjects of embellishment and ornamental design in all countries, and thus large sums of money have been spent upon them. The Germans in particular have given attention to carving upon their pipes scenes from real life, such as landscapes, battles, sleigh-

rides, boar-hunts, and illustrations of fairy tales and German legends. The heads of prominent men and of animals, and caricatures of all sorts, have been favorite subjects for pipes with the French and English. The hookah of the Eastern prince is even more elaborately wrought and is often embellished with gold and precious stones. Mention is mnde of a single Austrian pipe which cost $5,000.00 and Johnston says, with high official and rich private persons in Constantinople."* The cigar holder and tobacco-box are also a part of the paraphernalia of the smoker, and much money is spent upon them. Elaborate and costly tobacco-boxes were particularly fashionable during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. The snuff-box, too, is worthy of men-

tion. We find here the same lavish expenditure of money as in the case of the pipe. The finest of woods and precious stones, gold, silver, diamonds, and mosaics were used in their construction, and the art of both sculptor and painter was brought into requisition. XV.—THE HABIT.

Habit is defined as "a constitution or state of mind or body which disposes one to certain acts or conditions, mental or physical." Habits are originally the results of voluntary acts, but may pass beyond the control of the will. Wisely formed, they may be of the greatest advantage to man mentally, morally, and physically, while injudicious habits dissipate fortunes and destroy mind, character, health, and happiness. Paley called man a "bundle of habits." There is much truth in the remark, and a man's character is the algebraic sum of his habits, the good ones being regarded as positive and the bad ones negative. There are two kinds of habits.

lously avoided, not that they are all in themselves hurtful, but that they all have a tendency to grow and enslave those who indulge in them. They are like the coil of the boa, gradually tightening until their victim is crushed. The only really safe ground is total abstinence. These effects are most marked in the use of stimulants. An excited and abnormal condition of the body is produced, which is succeeded by a relapse. This leaves a languor and sense of malaise which crave relief. To obtain this relief, resort is again had to the stimulant. The new dose exaggerates the effects, and thus the matter grows worse and worse until the man is a wreck. In the case of tobacco, the physical effects are not so striking, but the enslavement is equally great. I desire here to suggest three reasons why young men in particular should not form this habit: 1. While it is fascinating and entertaining now, after a while it will disgust and annoy. 2. While it is popular and fashionable now, it will not be so a few years hence. You will have the misfortune to have on a dress not in the fashion. The chewer, particularly, and the smoker, in a measure, will soon be, as is the snuff-taker now, an object of remark and ridicule. 3. Your ability to perform successfully your life-work depends upon the freedom of your mind and body from enslaving habits. Such habits, while they may not shorten life, render old age imbecile, and unfit the mind for the proper performance of its work. It must ever labor under the high pressure of stimulants, and thus wears out the sooner. The associations of tobacco are very bad. Its most congenial home is the dram-shop, the gambling den, and the race-track. "Have a cigar," generally suggests, "Have a drink." When we see a cigar store we naturally look for bottles and glasses in the back room. The first cigar is but too often the first step towards rowdyism, dissipation, and degradation. It keeps such bad company that safety and propriety both admonish us to avoid it.

It is in America, too, that tobacco has its worst associations. In other countries its use is so universal that it can hardly be regarded as peculiar to places of ill-repute. In the United States those who use no tobacco at all are almost universally found among the best people of the land, and the anti-tobacco sentiment is growing so rapidly that we hope soon to see the cigar and the spittoon finally relegated to those places mentioned above, where they properly belong. There may be some exaggeration in the following lines by Petrus Scriverinus, but they are at least worthy of thoughtful consideration:

The social character of the habit of using tobacco is that, perhaps, which gives it its strongest hold upon the people. It is the whipper-in, so to speak. Here is found the cause of the first step. The cigar and snuff-box are passed around, and if you refuse to participate you are considered unsocial. The habit is fashionable and popular, and thousands are thus drawn in who would othervise not have the inclination to indulge.

In this way the habit is formed which charms indeed for a time, but in the end can only bring regret. Young men meet together to have a social smoke. Words flow freely, restraint is thrown off, and things are said and done which corrupt the mind and degrade the man. One of the foulest places I ever saw for black-guard, profanity, and indecent language was the smoking-room of an ocean steamer. Satan is present with every crowd of young men, and if they are not at some useful employment he will find something for them to do. I remember of being once at a little gathering at the home of a distinguished man. The party was quite select. None but married people were there and all were members of the Church. After dinner the gentlemen repaired to the smoking room and the ladies remained in the parlor. The conversation soon grew light and tales and anecdotes began to pass around. Some were told which it makes me blush to think of now. But for the cigar we would have remained with the ladies, our conversation would have been chaste, and our hearts had been unstained.

"Smoking induces drinking, drinking jaundice, and jaundice death." The effects of the use of tobacco upon the system as determined by the careful observation of physiologists are as follows:

1. Used in moderation, it produces no ill effects on most persons, and is supposed by some to promote digestion and produce a genial flow of animal spirits. 2. There are many persons to whom the smallest quantities are injurious. 3. Even its moderate use is universally hurtful to boys and young men before they reach maturity. 4. Intemperately used it produces chronic abnormal conditions of the system, such as

lips, fauces and mucous membrane of the mouth,

Furthermore, tobacco is not a prophylactic as has been sometimes supposed. On the contrary the tobacco user is the more susceptible to contagion and less able to combat disease when it has obtained a hold upon the system. All of these conditions and symptoms have been repeatedly observed by learned physicians, and cases illustrating each have been reported in medical journals. I have not space to quote such reports here, but the curious student who has not patience to examine the journals, will find ample illustration and proof in [Dr. John] Lizars' excellent [1859] little book on "The Use and Abuse of Tobacco.* I commend this to the careful consideration of the reader, because facts are arguments that are unanswerable. It is proper here to define what we mean by the moderate use of tobacco. After the long discussion which took place in the London Lancet in [January—April] 1857, the following definition of excess is given in a leading article:† 1. "To smoke early in the day is excess. 2. "As people are generally constituted, to smoke more than one or two pipes of tobacco, or one or two cigars daily, is excess. 3. "Youthful indulgence in smoking is excess." 4. "There are physiological indications which occuring in any individual case (how ever little may be used) are criteria of excess."

*Lindsay & Blackiston, Philadelphia. 1879. †Lizar's Use and Abuse of Tobacco, p. 84. [Ed. Note: Another edition of this oft reprinted book.] The same rules, of course, apply to the use of tobacco in any other form. Let those who claim to be moderate smokers measure themselves by these laws and see whether or not they are free from excess. From these general conclusions we infer that the use of tobacco is only permissible to a certain class of persons, and that in moderation. It has not been shown to be beneficial to these, and, therefore, on physiological grounds, there is absolutely no argument for the use of tobacco. On the contrary, there are the strongest reasons for its abandonment. Of all the methods of using tobacco, chewing is the most hurtful. Snuff-dipping is less injurious only because snuff contains less nicotine than chewing tobacco. They cause excessive spitting and excite the salivary glands to undue activity. The stomach is deprived of one of the chief agents in digestion and the whole body is enfeebled. The nervous system being alternately stimulated and depressed, is debilitated and the person grows irritable, restless, and nervous. If the immoderate use of tobacco continues, symptoms follow which are really alarming. The following are some of the symptoms which have been observed:

Now, I ask candidly, Is it the part of wisdom to tamper with a thing which produces such startling results? Some of these effects, particularly nervousness and dyspepsia, are more or less apparent with all tobacco users, and no medication is of avail as long as the practice continues. I call special attention to this fact that the victim of tobacco-poisoning does not usually attribute his ailments to the true cause.

He [the tobacco-victim] tries exercise, mineral waters, peptics, and dieting with no avail. He gives up in despair and turns anew to his tobacco as his only source of comfort and relief and feels that without it he would surely die. Smiff-dipping carries with it the same train of symptoms as chewing, and although snuff contains less nicotine, the effects are equally as great, because it is commonly used among women. Woman's nervous system is much more impressable than man's, and an amount of tobacco which would shock her system very severely, might be used by man with impunity. Dr. William A. Hammond, of New York, says,

The habit of dipping has unfortunately worked its way among some of the women of the higher classes in the South, and then it is usually practiced in secret. It cannot long be concealed, however, for the restless eye, the snuffy complexion, and the tainted breath inevitably betray the secret. The lady who values her health and regards her respectability, should not hesitate to tear herself away from so disgusting a practices, however much she may be its slave. Both chewing and dipping debilitate the gums, wear away, color, and injure the enamel of the teeth, make the breath offensive, and render the appearance of the mouth untidy and forbidding. It is sometimes claimed that tobacco preserves the teeth. This it can only do indirectly. The chief cause of the decay of teeth is uncleanness. The particles of food when not removed undergo decomposition and cause the teeth to decay. The use of tobacco has a tendency to remove this food. If there is a cavity in the tooth, it becomes filled with the tobacco, and this decaying slowly, acts somewhat like a filling. This reminds us of the swine's habit of cleansing himself by wallowing in the mud. Would not the timely assistance of the dentist and the free [Ed. Note: regular] application of the tooth-brush be much more consistent with common sense, decency, health, and economy? Snuffing is the least injurious of all the methods of using tobacco, and yet as a habit it is a most despotic master. John without his snuff-box is even more miserable than Pat without his pipe. Merat tells of a man who was found lying as if dead in the forest of Fontainebleau. On being aroused, he begged piteously for snuff. After this was given him, he soon revived enough to say that he had forgotten his snuff-box when he left home that morning, and that, "after he missed it, he had walked on as long as possible, but at last his longing for it became so intense that he was unable to move a step further." Snuffing injures the senses of smell and taste and produces dyspepsia. The habit however, is comparatively harmless, and yet it seems the silliest of all. Think of [Senator] Henry Clay [1777-1852] stopping in the midst of a speech and deliberately walking across the Senate hall to the public snuff-box on the vice-president's stand, taking a pinch of snuff, and returning to continue his speech! In that day the practice was very common and the snuff was furnished at the expense of the government. To-day the item of snuff enters the annual expense account of the Senate. The influence of smoking upon the system has been made the subject of accurate observation by numerous learned physicians, among whom we may mention

I can but briefly enumerate its observed effects. They are,

It causes the voice to become coarse and husky, and makes the articulation bad. Dyspepsia is not so common among smokers as among chewers. Smoking is also said to induce an inclination to strong drinks. The ill effects of the tobacco seem to be momentarily counteracted by the alcohol, and the stimulating effects of the intoxicating liquors are moderated by the tobacco. Thus it happens that drinkers are always smokers, and thus it is also that smoking often leads to drinking.

In this way the cigar with its associations have caused the ruin of many a young man. This fact too, perhaps, explains the German's ability to perform his prodigious feats of smoking and beer-drinking. Another effect is loss of courage and fortitude. [Dr. John] Lizars [1787-1860] says, "I have invariably found that patients addicted to tobacco smoking were in spirit cowardly, and deficient in manly fortitude to undergo any surgical operation, however trifling." Tobacco is issued to the European armies as a matter of policy and economy. It is known to impair the appetite and thus a saving is made daily of about five ounces of bread to the man. Individual degeneracy is one of the common results of the use of tobacco. It induces sensuality, and has a tendency to render the mind dull and inactive. The assertion that a man can do better work under the influence of the cigar is a falsity. The mind cannot elaborate more material than it has acquired. Some men can work better, no doubt, when smoking, for without the cigar they would be too dull and sleepy to do anything. I have no doubt if statistics could be obtained, the weight of intellectual clearness and ability would rest with the non-smoker.

And I say this not without authority. Some years ago the students in the Polytechnic School in Paris were divided into two groups—the smokers and non-smokers. In all the competitive examinations the smokers were far inferior to the others. In all my experience with classes of young men as a teacher, I have found the same to be true. Our best college students are always free from this pernicious habit. The case would not be so bad were it only a few individuals that are effected. But this is not so. National degeneracy follows as a natural result.

There is certainly something striking in the fact that the progress, activity, enterprise and intellectual power of the nations of the globe are to-day very nearly in inverse ratio to the amount of tobacco that they use. The list I think may stand about as follows:

I place the United States first, because I believe that in intellectual acuteness and activity, aggressive progress, and clearness and depth of thought, the American is unexcelled. England's intellectual position depends upon her past achievements rather than upon what she is doing at present. In saying this I do not mean to diminish the honors so justly due her. I simply suggest that she has not yet been able to accommodate her pace to the rapid march of modern times. The average German is proverbially dull and his work is always slow and labored. He accomplishes his ends with a greater outlay of energy than any one else. This is incontestably due to his beer and tobacco. The Frenchman is more vivacious and has greater intellectual acumen. The oriental spends his days in sensuality and semi-insensibility, scarcely arousing himself sufficiently to provide the necessities of life. India and China are walking upon the same dead level that their ancestors trod three thousand years ago. Why have they not caught the spirit of modern progress? They are drunk with the drugs of sensuality and bound with the chains of habit. If you will take tobacco and alcohol from them and give them Christianity, a new civilization will spring up among them and they will take their place among the first nations of the earth. The present degeneracy of Spain, Portugal and Turkey has been attributed to the inordinate use of tobacco. I will be pardoned here for making a few extracts. [Fulgence] Fiévée [de Jeumont (1794-1858)] says,

So also Lizars:* "Excessive smoking

Michel Lévy [1809-1872], in his Traite d'Hygiene [Publique et Privée (Paris: J. B. Baillière, 1850, reprinted 1857, 1862, 1869, 1879)], says,

This is a national question of no small moment. No man who smokes daily can be said to be at any time in perfect health. While the habit may produce directly no organic disease, it always causes functional disorders, and these are truly diseases. A nation of smokers must degenerate, because continued functional disorders prevent the full development of the man. This degeneracy is not observed among us, because the non-smokers and the women, the greater part of whom, be it said to their honor, do not use tobacco, act as a sort of a saving element to preserve the vigor of the race. If the American people desire the highest perfection to which a race can be brought, it must renounce tobacco forever.

I will close this section with a few extracts which will embody the opinions of men of the highest authority on this subject. Dr. Richardson, in his book on The Diseases of Modern Life [1876] gives the following conclusions:

Mr. Higginbottom says*:

*Lancet, 1857.

The following is from Dr. [Samuel] Solly [1805-1871], of St. Thomas's Hospital*:

The following extract is abridged from a paper published by the British Anti-Tobacco Society:

The Philadelphia Times has recently published articles from several leading physicians in regard to cigarette smoking, which is daily becoming more popular. The following is what Dr. Roberts Bartholow says on the subject:

I may give here an extract from the Christian Advocate on the same subject:

Dr. [Thomas] Laycock [1812-1876], of Edinburgh, a physician of great distinction, has written much on the subject of smoking. I cull the following from a paper in the Medical Gazette for 1846*:

____________ *See Lizar's Use and Abuse of Tobacco.

The following extract is taken from one of a series of recent sermons by Dr. Talmage on the "Ten Plagues of New York and Brooklyn:

These extracts might be almost indefinitely extended, but our space will not admit of further quotation. The literature on the subject is very extensive, and he who wants further proof of the positions I have taken will find ample material in standard medical works, in the medical and scientific journals, and even in the newspapers of the day. XIX.—HEREDITY. It is one of the first laws of biology that the physical and mental characteristics of the parent are transmitted to the child. Diseases and bodily defects of all sorts are transmissible. They do not always appear in the child. They may reappear in the third or fourth generation. It is not the disease that is inherited, but a constitutional defect and predisposition towards a certain class of diseases. For instance, in a family that has a tendency to insanity, one member will suffer from neuralgia, another will have epilepsy, a third will have an unbalanced character, a fourth may be a maniac, while a fifth may show no symptoms of the hereditary tendency. Nervous disorders are more markedly hereditary than any other constitutional defects, and reappear in the greatest variety of forms. They are all, however, unnatural and have their origin in some physiological sin with the individual affected or among his ancestors. In most cases they are traceable to some sort of intemperance and excess. Dr. Maudsley says, "Idiocy is a manufactured article, and although we are not ahvays able to tell how it is manufactured, still its important causes are known and are within control."Out of three hundred idiots in Massachusetts, Dr. Howe found that one hundred and forty-five were the offspring of intemperate parents. If the observation had extended to grand-parents, no doubt the number would have been greatly increased. Thus it is an established fact that an acquired infirmity in the parent may become in the child a permanent constitu- tional disability. The parent who has become nervous from bad habits has a child naturally nervous and excitable. An acquired craving for stimulants in the father is transmitted to the child as a constitutional disorder. Furthermore, the parent transmits to the child not only the tendency to the habit, but also a weakened constitution. The result is that the child is much more apt to run to excess than the parent was. The child that has inherited a taste for tobacco soon finds this unsatisfactory, and is exceedingly liable to resort to alcoholic drinks.

I have in mind now a number of cases where the sons of tobacco-using parents are addicted to both tobacco and whisky, and I have no doubt every one who reads this can call to mind similar cases. The conscientious father will certainly stop and think what a terrible legacy he is about to leave to his children.

This subject is further illustrated in the extracts given in the preceding section. I may add, however, the following sentiment from Dr. Pidduck.* "In no instance is the sin of the father more strikingly visited upon his children than the sin of tobacco smoking. The enervation, the hypochondriasis, the hysteria, the insanity, the dwarfish deformities, the consumption, the suffering lives and early deaths of the children of inveterate smokers, bear ample testimony to the feebleness and unsoundness of the constitution transmitted by this pernicious habit."____________ *See [Dr. John] Lizars' Use and Abuse of Tobacco [1856], p 96. The financial phase of this question is, perhaps, the one of most practical interest. Anything is to be avoided which costs the poor man a dollar without bringing him a just return. We have shown that tobacco brings no good results; that even moderately used it is a luxury of questionable propriety, and that intemperately used it brings most startling consequences. I take the position, then, that it is a luxury [a euphemism for brain damage] which very few can afford. Unfortunately, though, it is the poor man that is tobacco's greatest slave. In view of the returns it brings, considerations of economy alone should settle the question for every young man. Let us see. The moderate smoker uses three cigars per day. This may be taken as an average. These will cost him twenty-five cents. In one year [1882 era] this will amount to $96.25. Now, how many young men are there who can afford to invest $96 per year in a useless luxury? and how many fathers of families can well spare so much money annually? This amount put in a life insurance policy would secure a nice little fortune to a man's family at his death. But it is particularly upon the young man that I want to enforce this argument. A man in middle life or old age is not likely to form the habit, and if it is already formed at that time of life, he is not apt to leave it off. Suppose the young man is a lawyer, a physician, a teacher, or a preacher. In either case, his success depends very much upon his early acquisition of a good library. Let him begin at sixteen and judiciously invest the money in books which his more social friend spends in tobacco. At twenty-five, the time when he should think of taking a partner for life, he will have a handsome little library worth $866.25, all that he can possibly need at this time. At thirty the value of his books will be more than $l,200, and as a general rule he need not buy many more during life, whatever be his situation. This amount of books, well selected, is enough for the ordinary man, especially when he has access to a good public library. The other young man has burned up his $1,200, and has nothing to show for it but his nervousness and excitability. He wonders how his more prosperous friend can possibly manage to get so much money to spend for books. I know a young physician who complains all the time that he is too poor to buy books and instruments for his practice, and yet for the last five years he has spent at least $150 a year for tobacco and whisky. $750 would give a young doctor a right handsome outfit to start with. Thus the tobacco injures not only the man who uses it, but also those whom he is to serve. The preacher chews his tobacco at the cost of the moral welfare of his flock, the physician's cigar is paid for by the life-blood of his patient, and the teacher, besides soiling his shirt and staining his floor, sets his hearers an example which they will not only follow but pass beyond. I once knew a family where the father and mother and three sons were all intemperate tobacco users. Think of $400 a year for tobacco in one family! The three sons, too, were more or less addicted to intoxicating drink, and this increased the expense account. Here we have also another instance illustrating the ground I have taken in speaking of the hereditary influence of tobacco. While æsthetics is not duly appreciated by the masses, it is an element of civilization and refinement not to be ignored. Decency and neatness are certainly elements of good breeding, and I take the position that the use of tobacco is opposed to both. It lowers one's self-respect, else why does the gentleman always light his cigar in your presence with an apology, unless you accept the one he offers you? The young man, indeed, glories in the habit, but this is because he has not yet felt its sting. I have seldom met with a middle-aged man who did not regret having formed it. It is when the lightness of youth is past and sober realities of manhood are upon him, that man feels that he would like to rid himself of that chain which he realizes is gradually tightening. It is too late now, however. His children may do without bread, the poor may go away unclothed, his creditors may beg for their rights—he must have his tobacco. The tobacco chewer begins decently, but generally ends by spitting upon the grate, the stove, the carpet, and his own clothes. Accustomed to the nauseating fluid which he ejects from his mouth, he forgets how disgusting it is to those whose stomachs are not hardened to it. I have seen distinguished lawyers, rich merchants, learned physicians, college professors, and even ministers of the gospel—I speak it with shame—whose mouths, shirt-fronts, and beard were ever stained with this over-flowing of tobacco juice. Not long since I saw an official at his desk with a yellow stream flowing from each corner of his mouth down upon his snow-white beard and his shirt, and occasionally dropping upon the paper on which he wrote. Now I am aware that the men who go to such an excess of indecency are considered exceptions, and the tobacco chewer generally will claim exemption from this charge. I accept the plea, but must say,

Then, furthermore, you, too, will probably go the same road. While some mm do preserve through life a moderate decency, to the majority [99½%] it becomes one of the filthiest of filthy habits. It taints the breath, eolors the teeth, renders the mouth disgusting, and makes the man offensive to those who do not use the weed, particularly so to woman. I pity the wife who has to endure kisses from such a mouth. King James in his Counterblaste [1604] says,

Smoking, as has been said, is more decent but equally as senseless. Were we not accustomed to the habit, it would appear to us as ridiculous as the ring in the nose and lip of the barbarian. The smoker's breath is much worse than the chewer's, his complexion is more affected, and if he chews his cigar, as he often does, he is entitled to credit for all the indecencies of the chewer. Snuff-dipping involves all of the filthiness of chewing, and this is exaggerated because it is woman instead of man that practices it. So conscious, too, is she of her guilt that she strives to keep it a secret. The man smokes and chews in his office, in his parlor, on the street, and in the assembly, but the woman hides away in her chamber and plies her brush, admitting only her most intimate and confidential friends. Poor woman! you do not know that the secret you are so profoundly keeping is already on everybody's lips. 1. It is fashionable. We are not justified in following fashion when our health, our pecuniary interests, our usefulness, the good of our children, or our own self-respect will be thereby compromised. 2. It is genial company. So are evil companions when we have learned to associate with them. But this is no reason why we should not forsake them. Besides, this is a morbid taste. It is company which we would never naturally desire. 3. It soothes the nerves and enables one to do better work. We have shown that it only temporarily allays the nervous excitement which its use has caused. If it had never been used, it had never been needed. Then the trouble grows  (pp 132-133) no idea that there is any man addicted to the habit who has not had serious misgivings about it, and my observation has been that it is a matter of great self-congratulation to any man when he success-fully rids himself of it. I will now recapitulate some of the principal reasons why I think the use of tobacco should be discouraged. 1. While it is a source of great present revenue to the people who cultivate it, it will in the end be detrimental to the country, because it is a crop which is very exhausting to the soil and soon wears out the land. Besides, it is not to the buyer a just equivalent for the money he pays for it. 2. The use of tobacco is a habit which continually grows stronger, at the same time weakening the will, and finally making man its abject slave. Such habits are sedulously to be avoided, although they could be shown to have no other ill effects. 3. Its associations are very bad. It is the inseparable companion of dram drinking, gambling, loafing, and sporting. It is the universal habit of the adventurer, the villain, the roué, and the debauchee. I would much rather not be found in such company. 4. As a social habit, it makes one acquainted with strange companions. It makes the spirits flow, opens the lips and lets forth the poisonous and polluted words which come from a corrupt heart. In the same way it encourages loafing, lounging, and laziness. 5. Its physiological effects, unless very carefully and moderately used, are such as to warrant its abandonment, even if there were no other considerations. For these the reader is referred to the discussion of this part of the subject. 6. All its ill effects are transmitted from parent to child, and usually with a weakened constitution and a disposition to intemperance. The physiological legacy which a child receives is one of which it cannot dispossess itself. The parent, then, cannot be too careful in this matter. 7. It is a filthy habit. This is particularly so of chewing and snuff-dipping. It colors the teeth, makes the complexion sallow, renders the personal appearance forbidding, makes the breath offensive, and always causes the loss of a modicum of self-respect. Such a habit can only be justified in consideration of its benefits. No benefits have been shown to accrue in this case. 8. It is an expensive habit. Were it not hurtful, it might be indulged in as a luxury by well-to-do people who could afford it. Its physiological effects, however, have been shown to be so bad that it ought to be avoided even by these. The man who lights his Havanna with a dollar bill puts it to a much better use than he did the one with which he bought the cigar. 9. It is of doubtful morality, because its consequences are bad.

|

[In interim, pending completion of this site, you may

obtain this book via your local library, or online at google.]

Other Books on Tobacco Effects

Physical, Intellectual, and Moral Effects on The Human System, by William A. Alcott, M.D (1836) The Mysteries of Tobacco, by Rev. Benjamin I. Lane (1845) The Use and Abuse of Tobacco, by Dr. John Lizars (1859) Tobacco and Its Effects: Report to the Wisconsin Board of Health by G. F. Witter, M.D. (1881) The Tobacco Problem by Meta Lander (1882) The Case Against the Little White Slaver, by Henry Ford (1914) Click Here for Titles of Additional Books |

Children's Knowledge In That Era

Children's Books' Data on Tobacco |

Subsequent Reactions in Law

Tennessee's 1897 Cigarette Sales Ban Michigan's 1909 Deleterious Cigarette Ban And Parallel Pure Air Cases |

References on Anti-Indian Activity

| Wikipedia re Oneida Indian Nation