![]()

This right of freedom from nuisances is a right of long-standing, an ancient right. The right of ours is a common law right. Our right to pure air has been developed since at least the year 1306, actually back to Hammurabi and the "Love thy Neighbor" Mosaic Moral Code.

| “The smoker of cigarettes is constantly exposed to levels of carbon monoxide in the range of 500 to 1,500 parts per million when he inhales the cigarette smoke.”—G. H. Miller, Ph.D., “The Filter Cigarette Controversy,” 72 J Indiana St Med Ass'n (#12) 903, 904 (Dec 1979). |

| “The blood of cigarette smokers will contain from 2 to 10 percent carboxyhemoglobin . . . initial symptoms of poisoning . . . will result from exposures to 1,000 ppm for 30 minutes or 500 ppm for one hour. One hour at 1500 ppm is dangerous to life. Short exposures (one hour) should not exceed 400 ppm.”--Julian B. Olishifski, P.E., C.S.P., Fundamentals of Industrial Hygiene, 2d ed (National Safety Council), pp 1039-1040. |

| “[L]ittle mixing takes place, as can be seen by watching smoke plumes rise in still air. Even when the plume is disturbed, the visible core can be observed to maintain homogeneity over a distance of one to three meters . . . .

“the core with concentrations of tens to hundreds of parts per million of the powerful irritants acrolein [150 ppm] and formaldehyde [30 ppm] can readily contact eyes or be breathed with only slight dilution. “The irritant [bad smell] properties of these materials may be partly inferred by their occupational limits. These are 0.1 to 0.3 ppm for acrolein and 1 to 3 ppm for formaldehyde.”—Howard E. Ayer, M.S., David W. Yeager, B.S., “Irritants in Cigarette Smoke Plumes,” 72 Am J Pub Health (#11) 1283 (Nov 1982). |

The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General (Surgeon General Report, 27 June 2006), and "Novel MRI Technique Shows Secondhand Smoke Damages Lungs" (Breitbart News, 26 Nov 2007), each verifying once again the danger.

City Fire Ins Co v Corlies, 21 Wendell 367; 34 Am Dec 258 (NY, July 1839) Stone v Mayor of N. Y., 25 Wend 157, 173; 14 Common Law Rep 802 (1840) Russell v Mayor, etc., of N. Y., 2 Den 461, 475; 17 Common Law Rep 192, 197 (1845) (cases involving the 1835 New York fire wherein the Mayor had buildings blown up ahead of the advancing flames, for a fire-break to head off the fire, and was upheld in such fire-halting actions; the pertinent public safety principle covers not only fires, but also "pestilential diseases, or any other threatened and blighting evil").

| Bowditch v Boston, 101 US 16, 18; 25 L Ed 980 (5 April 1880) said: "At the common law everyone had the right to detroy real and personal property, in cases of actual necessity, to prevent the spreading of a fire, and there was no responsibility on the part of the destroyer, and no remedy for the owner. . . .

"There are many other cases besides that of fire, some of them involving the destruction of life itself, where the same rule is applied. 'The rights of necessity are a part of the law.' Respublica v. Sparhawk, 1 Dall., 357, 362 [1 L Ed 174, 177 (Pa, 1788)]; see also Mouse's Case, 12 Rep. (Coke), 63 [81 Eng Rep 341 (1675)]; 15 Vin., tit. Necessity, sec. 8; Cast Plate Co. v. Meredith, 4 T.R., 794; Am. Print W. v. Lawrence, 1 Zab., 248; 3 Zab., 591 [57 Am Dec 420 (NJ, 1851)]; Stone v. Mayor of N. Y., 25 Wend., 173 [14 Common Law Rep 802 (1840)]; Russell v. Mayor, etc., of N. Y., 2 Den., 461 [17 Common Law Rep 192 (1845)]." |

- smoke or smoking as a nuisance;

- as trespassing;

- as garbage;

- as ultrahazardous conduct in motion coming to the injured person; and

- the "pesthouse" concept due to its transmitting/causing disease.

(Of course, the better approach is an institutionalized written law banning tobacco manufacture and sales, to avoid having masses of individual victims having to suffer en masse perhaps for decades. Some states have passed such institutionalized constitutional-rights-enforcing laws, e.g., Iowa, Tennessee, Michigan. Note the historic context in which the tobacco lobby opposes such laws, infra.)

| 6 ALR 1574 | Balancing | Nuisances

| US Supreme Court

| Michigan

| Other States

| |

Some Case Law Precedents Listed in

Some Case Law Precedents Listed in

Annotation: Nuisance Resulting from Smoke

Alone as Subject for Injunctive Relief,

6 ALR 1574 (1920)

|

Cartwright v Gray, 12 Grant, Ch (UC) 400 (Canada, 1866) ("a much quoted case" saying that "I consider it to be established by numerous decisions that smoke unaccompanied with noise or noxious vapor, that noise alone, that offensive vapors alone, although not injurious to health, may severally constitute a nuisance to the owner of adjoining or neighboring property; that if they do so, substantial damages may be recovered at law, and that this court, if applied to, will restrain the continuance of the nuisance by injunction in all cases where substantial damages could be recovered at law.") Cartwright v Gray, 12 Grant, Ch (UC) 400 (Canada, 1866) ("a much quoted case" saying that "I consider it to be established by numerous decisions that smoke unaccompanied with noise or noxious vapor, that noise alone, that offensive vapors alone, although not injurious to health, may severally constitute a nuisance to the owner of adjoining or neighboring property; that if they do so, substantial damages may be recovered at law, and that this court, if applied to, will restrain the continuance of the nuisance by injunction in all cases where substantial damages could be recovered at law.")

For a comprehensive listing of precedents and analysis of the "nuisance" concept, see Matthew J. Canavan, ed., Vol 66, Corpus Juris Secundum, "Nuisances," pp 523-744, §§ 1-167 (St. Paul: West Pub, 1998). |

Other Cases Against Smoke

A smoker challenged the ban. The appeals court upheld it, using classic pure air terminology: "A nuisance belongs to 'that class of wrongs that arise from the unreasonable, unwarrantable, or unlawful use by a person of his own property . . . or from his own improper, indecent, or unlawful personal conduct, working an obstruction of or injury to a right of another, or of the public, and producing such material annoyance, inconvenience, discomfort, or hurt that the law will presume a consequent damage' . . . . There is no doubt that smoking . . . caused to a great majority of the people . . . material annoyance, inconvenience, and discomfort. . . . There is not only discomfort, but positive danger to health, from the contaminated air . . . ."

"The city council . . . had authority . . . to provide for the public health. It can therefore require . . . that there shall be ventilation for a supply of fresh air . . . and, in pursuance of the same power, it can, in order to preserve pure and fresh air . . . prohibit smoking . . . It is essential to health and to comfort to have pure air . . . .")

|

“As early as 1306 a royal proclamation was issued, forbidding the use of coal in London, followed by a commission to punish miscreants 'for the first offence with great fines and ransoms, and upon the second offence to destroy their furnaces.'”—Margaret White Fishenden, Mechanical Engineering Dep't, Imperial College of Science and Technology, Univ of London, “Smoke and Smoke Prevention,” Encyclopćdia Britannica, Vol 20, pp 840-842 (Law §, p 841) (1963). “As early as 1306 a royal proclamation was issued, forbidding the use of coal in London, followed by a commission to punish miscreants 'for the first offence with great fines and ransoms, and upon the second offence to destroy their furnaces.'”—Margaret White Fishenden, Mechanical Engineering Dep't, Imperial College of Science and Technology, Univ of London, “Smoke and Smoke Prevention,” Encyclopćdia Britannica, Vol 20, pp 840-842 (Law §, p 841) (1963). |

"Balancing the equities" is a term you may hear. Laymen claim that smokers and nonsmokers' rights must be "balanced." Such assertions are almost invariably out of legal context, (a) disregarding the definition, and disregarding (b) pertinent legal principles, thus accessory to the "universal malice." There are many pertinent court precedents of which the following are examples:

|

|

Summary: As per 26 Am. Jur. 2d Eminent Domain § 137 (1996), “The constitutional requirement of just compensation may not be evaded or impaired by any form of legislation, and statutes which conflict with the right to just compensation will generally be declared invalid.” Of course, better yet, an injunction, to prevent/stop the 'taking.' |

Pertinent United States Supreme Court Cases

|

At 1039, "We cannot doubt that the police power of the State was applicable and adequate to give an effectual remedy. . . . It rests upon the fundamental principle that everyone shall so use his own as not to wrong and injure another. To regulate and abate nuisances is one of its ordinary functions." The Supreme Court then cited a case wherein a practice since May 1697 was held peremptorily banned: Coates v Mayor, etc., of New York, 7 Cow 585 [9 NY Com Law Rep 230 (Oct 1827)]. Quoting, it said, "'Every right . . . is . . . holden subject to the restriction that it shall be so exercised as not to injure others. Though at the time it be remote and inoffensive, the [offender] is bound to know at his peril that it may become otherwise . . . and that it must yield. . . .'" Continuing at 1039: "In such cases, prescription, whatever the length of time, has no application. Every day's continuance is a new offense, and it is no justification that the party complaining came voluntarily within its reach. Pure air and the comfortable enjoyment of property are as much rights belonging to it as the right of possession and occupancy. If population, where there was none before, approaches a nuisance, it is the duty of those liable at once to put an end to it. Brady v Weeks, 3 Barb., 157 [NY, 19 May 1848]." "By our law, indeed, either public officers or private persons may raze houses to prevent the spreading of a conflagration. But this right rests on public necessity, and no one is bound to compensate for or to contribute to the loss, unless the town or neighborhood is made liable by express statute. 2 Kent, Comm. 338, 339; Bowditch v. Boston, 101 U.S. 16; Taylor v. Plymouth, 8 Metc. ([49] Mass.) 462 [Oct 1844]; The John Perkins, 21 Law Rep. 87, 97, Fed. Cas. No. 7,360 [(CC Mass)]; The James P. Donaldson, 19 Fed. 264, 269 [(ED Mich, 1883)]. Another instance of a right founded on necessity is the case of The Gravesend Barge, or Mouse's Case, decided and reported by Lord Coke, in which it was held that in a tempest, and to save the lives of the passengers, a passenger might cast out ponderous and valuable goods, without making himself [157 U.S. 386, 406] liable to an action by their owner. 12 Coke, 63, 1 Rolle, 79; 2 Bulst. 280." 157 US 405-406; 15 S Ct 664; 39 L Ed 751. And, per dissent, "No one has a right to have his property burn, if thereby the property of others is endangered." 157 US 423; 15 S Ct 671; 39 L Ed 757, citing Wamsutta Mills v Old Colony Steamboat Co, 137 Mass 471; 50 Am Rep 325 (1884). TTS of course is a matter of smokers starting fires burning property, with a "natural and probable consequence" being the injury of others. |

|

|

|

|

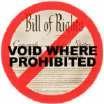

| As enforcement of the Bill of Rights is mandatory, people can not legally vote directly or indirectly (e.g., via their local, State, or Federal governments or representatives) to violate people's constitutional rights.

"The very purpose of a Bill of Rights was to withdraw certain subjects from the vicissitudes of political controversy, to place them beyond the reach of majorities and officials and to establish them as legal principles to be applied by the courts. "One's right to life, liberty and property, to free speech, a free press, freedom of worship and assembly, and other fundamental rights may not be submitted to vote; they depend on the outcome of no election." West Virginia State Board of Education v Barnette, 319 US 624, 638; 63 S Ct 1178; 87 L Ed 1628 (1943). And Romer v Evans, 517 US 620; 116 S Ct 1620; 134 L Ed 2d 855 (1996). Government aiding and abetting private individuals in violating a right is unconstitutional, i.e., when e.g., “. . . States have made available to [private] individuals the full coercive power of government to deny” other individuals their rights.—Shelley v Kraemer, McGhee v Sipes, 334 US 1, 19; 68 S Ct 836; 92 L Ed 1161 (1948). Laws, government-wide regulations, etc. are non-negotiable, not subject to repeal by contract. See, e.g., 29 USC § 141 and 5 USC § 7117(a)(1). Compare West Virginia State Board of Education v Barnette, 319 US 624, 638; 63 S Ct 1178; 87 L Ed 1628 (1943) and Romer v Evans, 517 US 620; 116 S Ct 1620; 134 L Ed 2d 855 (1996) (no vote allowed to repeal constitutional rights). See also "Clean indoor air laws are easily implemented, are well accepted by the public, reduce nonsmoker exposure to secondhand smoke, and contribute to a reduction in overall cigarette consumption. . . . The vast majority of scientific evidence indicates that there is no negative economic impact of clean indoor air policies, with many studies finding that there may be some positive effects on local businesses. This is despite the fact that tobacco industry-sponsored research has attempted to create fears to the contrary."But see how pushers arrange for the rights herein cited, to be sabotaged, via the "Freeport Doctrine." |

TTS Lawsuits Pertinent to the

"Right to Fresh and Pure Air"

Job Related Cases Negligent Hiring Cases Cost Recovery Cases By Health Groups/States Custody and Divorce Cases Condominium/Apartment TTS Cases |

Tennessee's Cigarette Selling Ban Michigan's Deleterious Cigarette Ban Prosecuting Tobacco Pushers for the Foreseeeable Deaths They've Caused Include in All Zoning and Business Licenses, A Requirement to Comply With All Pertinent Laws |

For More Tobacco Effects Information

Links to Related Sites |

Smokers' Posing A Danger

to Others

Due to Their Disproportionate

Behavior/Conduct

Beyond the TTS Danger

Birth Defects | Costs Crime | Divorce Drugs | Fires These impacts on others are oft overlooked in the focus on mere TTS/ventilation issues. |

Common Law Rights to

Life Remain in Force

| See Silver v Silver, 280 US 117, 122; 50 S Ct 57; 74 L Ed 221 (1929) for guidance on the creation of new common law rights, or abolition of old ones to obtain a constitutional legislative goal.

The common law is not repealed unless a law's language is clear and explicit for the purpose, Fairfax v Hunter, 11 US (7 Cranch) 603; 3 L Ed 453 (1813). "Where rights are infringed, where fundamental principles are overthrown, where the general system of the laws is departed from, the legislative intention must be expressed with irresistible clearness, to induce a court of justice to suppose a design to effect such objects." U.S. v Fisher et al, 6 US (2 Cranch) 358, 390; 2 L Ed 304, 314 (1804). "Laws are construed strictly to save a right."— Whitney et al. v Emmett, et a1., 1 Baldwin C. C. R. 316. Government aiding and abetting private individuals in violating the right to pure air is unconstitutional, i.e., when ". . . States have made available to [private] individuals the full coercive power of government to deny" other individuals their rights. Shelley v Kraemer, McGhee v Sipes, 334 US 1, 19; 68 S Ct 836; 92 L Ed 1161 (1948); and Blackstone. Your right to life, and due process before you can be killed, of course, cannot be repealed, not constitutionally or pursuant to the Bill of Rights, so no 'enabling act,' e.g., in TTS context, no 'pre-emption law,' can be, or is, constitutional. Smokers who allege “their rights,” you can answer them by dsaying, for example: Yes, “smokers should have the right to put a loaded 38 snub-nosed Smith & Wesson in their mouth and pull the trigger. But their rights stop when they take my body with them when they PULL that trigger!” — Patty Young. Genuine rights, your pure air anti-nuisance rights, in these matters are "present rights," for the "here and now." If you are being affected by violation of these rights being described, do not accept typical anti-law answers such as, 'if you don't like it here, go away.' Courts have repeatedly shown that rights are for where you are, to be enforced and obeyed there. See cases such as Indeed, government aiding and abetting private individuals in violating a right is unconstitutional, i.e., when ". . . States [governments] have made available to [private] individuals the full coercive power of government to deny" other individuals their rights. Shelley v Kraemer, McGhee v Sipes, 334 US 1, 19; 68 S Ct 836; 92 L Ed 1161 (1948). See also David Morris, "Texas Judge Rules 'The Sky Belongs To Everyone'" (26 July 2012) (“Texas judge rules atmosphere, air is a public trust . . . The 'public trust' doctrine is a legal principle derived from English Common Law. . . In 2007, in a law review article [Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review, p 577, vol. 34, Iss. 3, 1-1-2007] University of Oregon Professor Mary Christina Wood elaborated on similar idea of a Nature’s Trust. 'With every trust there is a core duty of protection,' she wrote. 'The trustee must defend the trust against injury. Where it has been damaged, the trustee must restore the property in the trust.' She noted that the idea itself is not new. In 1892 'when private enterprise threatened the shoreline of Lake Michigan, the Supreme Court said, ‘It would not be listened to that the control and management of [Lake Michigan]—a subject of concern to the whole people of the state—should . . . be placed elsewhere than in the state itself.’ You can practically hear those same Justices saying today that ‘[i]t would not be listened to’ that government would let our atmosphere be dangerously warmed in the name of individual, private property rights.”) See also the law review article by Prof. Alfred W. Blumrosen, Donald M. Ackerman, Julie Klingerman, Peter VanSchaick, and Kevin D. Sheehy, "Injunctions Against Occupational Hazards: The Right to Work Under Safe Conditions," 64 California Law Review (#3) 702-731 (May 1976) (the right to safety is where you are, not elsewhere). The same is true of the right to be free from pollution, whether chemical, particulate, noise, or whatever. These rights protect everyone, even so-called "hyper-sensitive" persons (meaning, persons previously exposed, hence, more alert to the danger, less unwary, less deceived by pro-pollution disinformation): See for example Michigan Standard Jury Instruction (SJI 2d) 50.10, "Defendant Takes the Plaintiff As He/She Finds Him/Her": "You are instructed that the defendant takes the plaintiff as he / she] finds [him / her]. If you find that the plaintiff was unusually susceptible to injury, that fact will not relieve the defendant from liability for any and all damages resulting to plaintiff as a proximate result of defendant's negligence" (January 1982). This rule SJI 2d 50.10 cites Daley v LaCroix, 384 Mich 4, 13; 179 NW2d 390, 395 (1970) and Richman v City of Berkley, 84 Mich App 258; 269 NW2d 555 (1978), as pertinent precedents. |

For More 'Pure-Air' Legal References

|

"Validity of Regulation of Smoke and Other Air Pollution," 78 ALR2d 1305 (1961) J. W. Tubbs, The Common Law Mind: Medieval and Early Modern Conceptions (Johns Hopkins, 2000) Cheryl Sbarra, "Legal Authority to Regulate Smoking and Common Law Threats and Challenges" (April 2004) http://burningissues.org/ |

|

Airspace Action, Physicians for Smoke-Free Canada, et al. v Premier of British Columbia, et al, File #16958, Case No. 2020014 (BC Human Rts Comm'n, 15 Oct 2001)

American Lung Association v Environmental Protection Agency, US App DC, 134 F3d 388 (30 June 1998) cert den US, 120 S Ct 58; 145 L Ed 2d 51 (4 Oct 1999) (Issue of Sulfur Dioxide [SO2] in Air) |

Request to EPA 3-23-2001

| To: EPA Administrator Christie Whitman

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20460 "Cigarettes contain and emit large quantities of toxic chemicals, as per references cited at our https://medicolegal.tripod.com/toxicchemicals.htm. "The tobacco danger was known and widely reported in the 19th century. Various states including Iowa banned cigarette manufacture and sales in 1897, background at our https://medicolegal.tripod.com/iowalaw1897.htm. "Tobacco has been linked in research, to other issues than mere 'health' ones, as per data sites linkable from our https://medicolegal.tripod.com/effects.htm. "Please consider advising the President and Congress of the 1897 Iowa cigarette manufacturing ban, with a view to having Congress adopt such a law on a nationwide basis. The tobacco danger is now better documented than in 1897! And then it was enough to warrant the manufacturing ban! "Of course, if EPA already has authority to ban cigarette manufacture, please exercise it." See EPA's Daily Pollution Readings: 150+ Cities |

Smokers Are Foreseeably Dangerous:

Cases on Suing Practitioners

for Negligence vis-a-vis Dangerous

Mentally Disordered People

| Smoking involves mental disorder.

That is an underlying factor on smokers' dangerousness. There has been litigation against practitioners for negligence in regard to protecting third-parties from dangerous, mentally ill people.

Examples: Of course, the real solution, the real prevention, is institutionalized solution, cigarette bans, criminal prosecutions. Tobacco use notoriously causes brain damage, as known for over four centuries. Aspects of tobacco-caused mental disorder include but are not limited to abulia, anosognosia, confabulation, dyscalculia, delusions including of grandeur, dyslexia, fragmentation, hallucinations, impaired reasoning ability, intoxication, mental disorders, psychopathology, time disorientation, and unresponsiveness to normal stimuli. Accordingly, pursuant to their brain damage symptoms, smoker commonly hallucinate that there is a "right to smoke." There is not, of course, nothing in the Constitution, Bill of Rights or common law, on such a right. On the contrary, there is no right to ingest poison, i.e., to consent to such bodily injury, much less, to spew poison! causing injury and death to others! And see this response presented by one nonsmoker: Yes, “smokers should have the right to put a loaded 38 snub-nosed Smith & Wesson in their mouth and pull the trigger. But their rights stop when they take my body with them when they PULL that trigger!” — Patty Young. |

Ten Easy-Maintenance Trees

for Northeast and Midwest States

|

Baldcypress (Taxodium distichum) 50-70'

Cimaron Green Ash (Fraximus pennsylvanica 'Cimmaron') 60' Ginkgo or Maidenhair Tree (Ginkgo biloba) 50-80' Golden Raintree (Koelreuteria paniculata) 30-40' Ivory Silk Lilac (Syringa reticulata 'Ivory Silk') 20-25' Macho Amur Corktree (Phellodendron amurense 'Macho') 20-30' Pacific Sunset Maple (Acer truncatum x platanoides) 40' Sawtooth Oak (Quercus acutissima) 35-45' Sterling Silver Linden (Tilia tomentosa) 50-70' Upright European Hornbeam (Carpinus betulus 'Fastigiata') 35-40' Note that although chestnut trees used to be common in the U.S., they were killed in the 19th century.—Susan Freinbel, "If all the trees fall in the forest . . . ," 23 Discover (#12) 67-73 (Dec 2002). |

Air Cleaning Plants

| Arrowhead

Bamboo palm 6' Bostern Fern, stiff drooping leaves Bromeliads Draecena - helps remove trichlorethylene English Ivy Fiscus Alii - tree-like Golden Pathos Orchids Peace Lily - helps remove acetone, benzene, formaldehyde, trichlorethylene Rubber Plant - helps remove formaldehyde Schleffera Spider Plant Details: Wm Wolverton [Ex-NASA Environmental Scientist], How to Grow Fresh Air James Dulley, Update Bulletin 586 (DFP 11-17-02 G1) Wildflower Info Center Ruth Stout, Gardening Without Work (1974). See also related Mulching Video |

| If you feel that this is very basic information, which everyone already knows, I agree. This data is on the basic order of, 'people can't shoot you,' 'can't stab you,' 'can't poison you.' But many people do not comprhend and apply these basics.

Back at Lincoln's time, most average persons could understand constitutional law, and would listen for hours to lectures on the subject. See, e.g., the Lincoln at Peoria Speech (1854). Nowadays, average people's knowledge of the subject is deteriorated down to the "sound-byte" level, as per the "dumbing-down" of education. "Due process of law," you know. Yes, there are laws against murder. The "right to pure air" and the "right to put out fires" are all indeed in the same family of rights, the basic right to life. We write this, to you, basic information, because other people don't know the material. In America, there was some objection to even having the Bill of Rights, of which the Fifth, Sixth, Eighth and Ninth Amendments are a part. Some of the 'Founding Fathers' thought rights were obvious, inalienable, nobody would ever dispute or deny them! Sadly, we have learned that rights our ancestors took for granted, thought everyone would know!, were later disputed, denied! For example, the right to petition was being denied by 1839, even though it is a listed right! See the analysis by Gerrit Smith, Letter 1839), p 4. And see Christine Meisner Rosen, "Responses to Industrial Pollution: Conflict and Confusion in the Courts (1840-1865)" And Shirley Brandle, WoodBurnerSmoke.net/Videos.htm And Robert Starkey, "Deconstructing the Tobacco Paradigm" (25 March 2010). Take the Sierra Club 'Green' Test. And remember this aphorism from almost a century ago (1935): “It was believed that you could not make make men good by act of Parliament [Congress, Legislature, etc.] We now know that you cannot make them good any other way.”—George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950), in "Preface to Androcles and the Lion from Nine Plays" (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1935), p. 880. |

Here Is An Error To Avoid

When Seeking Smoke-Free Air—

Failing To Mention ALL Tobacco Correlatives

(The 19th Century Had More Success Because

They Cited More Than Just "Health" Issues)

The 20th Century Lost That Momentum

Because Activists Stopped Citing

The Full Range of Tobacco Correlatives:

Place In Your Activist Group Bylaws

Four (4) Crucial Points

As Per the Constitution, Laws, and Court Precedents

Must Be Cited to Officials, And

None Are to Be Omitted/Overlooked

and Mental Disorder Is Not Only Not a Right,

But a Mental Disorder to be Avoided

Examples of Smoke-Free State Activities

California, Delaware, New York, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Montana, and Vermont all passed smokefree workplace legislation by September 2005.

In January 2006, New Jersey became the 11th state with such a law, joining the above states and Washington. In March 2006, Utah became the 14th state with such a law, after Washington, Puerto Rico, and Washington DC. In November 2006, Hawaii went smoke-free. Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada will soon have strong laws as well, thanks to voter-approved initiatives adopted in November 2006. "New Mexico bans smoking in almost all indoor workplaces: New law begins June 15 [2007]" (by Walter Rubel, The Daily Times (Farmington, NM) 3/14/2007 Milton J. Valencia, "Parks’ smoking ban taking effect immediately" (Boston Globe, 31 December 2013) ("The Boston Parks and Recreation Commission approved a smoking ban Monday in city-run parks . . . . The ban covers the 251 parks, squares, cemeteries, and other spaces run by the Parks and Recreation Department, including Boston Common, the Public Garden, and Franklin Park.") |

Examples of Smoke-Free Restaurant States

| California, Delaware, New York, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Montana, Vermont, Washington, New Jersey, Utah, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Hawaii, Arkansas, North Dakota, Puerto Rico, Guam, Washington DC, Louisiana

"Straight Talk About Smoke-Free Workplace Laws" (on benefits of smoke-free policies to businesses). See context. See Kansas cases, e.g., |

Example of Ban of Smoking Around Children in Automobiles

|

Even riding with a smoker by car is likewise dangerous due to the high toxic chemical emissions' level. A "British Study Reveals Alarmingly High Levels of Interior Pollution in Smokers’ Cars" (19 October 2012). "The . . . World Health Organization (WHO) recommended safe level is 25 µg/ micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3). While non-smoking trips were well below that level [a mere 7.4 µg/m3], interior pollution in trips with smoking drivers averaged a far higher 85 µg/m3.

Moreover, according to the study, peak levels averaged 385 µg/m3 and on one occasion, the readings were off the scales, with 880 µg/m3. Opening the windows or turning on climate control didn’t improve the situation, as the pollution levels inside the car still exceeded the WHO [safe] levels."

Maine. In signing, the Governor said, "Tobacco use costs too many lives and too much money." "Especially at risk are our youngest citizens, who don’t have the choice of whether or not to be exposed to dangerous secondhand smoke." Nova Scotia and the Yukon, Canada, the Yukon "bans smoking in public places," "including restaurants, bars, correctional centres, schools, community centres, and tents used for special events," in "company vehicles with two or more people inside," and "in vehicles with minors inside," and "prohibits retailers from displaying tobacco products or advertising in their stores." |

Examples of Smoke-Free National Activities

| Fenton Howell, "Ireland's workplaces, going smoke free," 328

British Med J 847-848 (10 April 2004)

BBC News UK Edition, "India outlaws smoking in public" (2 May 2004) Norway (1 June 2004) (Background and Effort to Ban Tobacco Selling (18 June 2013): "Prohibition is the only logical answer to the knowledge we have.") New Zealand, Malta, Sweden, Uganda Bhutan (November 2004, prohibits smoking and tobacco sales, "local belief . . . traces the tobacco plant's origin to a she-devil," Time, 21 Feb 2005, p 19) Italy (10 January 2005) Scotland (30 June 2005 effective 26 March 2006) "Europe's 'no smoking' zones" (The Indpendent, 5 Jan 2006) Policy Announcement, February 2006 United Arab Emirates (UAE) (25 February 2006) French-Speaking Quebec and English Speaking Ontario (1 June 2006) Nations Through October 2006: The countries of Ireland, Italy, Scotland, England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Norway, Sweden, Finland, New Zealand, Bermuda, Uganda, Malta, Uruguay, Hong Kong, and Bhutan have enacted comprehensive smokefree workplace legislation, including smokefree restaurants and bars. Good idea in view of tobacco ingredients and hazards. France as of 16 Nov 2006 published its new smokefree workplace law. Effective 1 February 2007, workplaces other than restaurants, bars and nightclubs, must be smokefree. Effective 1 January 2008, restaurants, bars, and nightclubs must be smokefree. Outdoor areas of educational institutions other than universities must also be smokefree. Venzuela is increasing cigarette taxes, says "The price of vice increases in Venezuela" (CNN, 15 October 2007). "The Venezuelan government is placing a higher tax on alcohol and cigarettes in an effort to cut consumption and prevent what it views as the social, economic and moral consequences of drinking and smoking. . . . Taxes on cigarette imports have also increased, from 50 percent to 70 percent of the total price." In Bavaria, in Germany, the smoke-free law was upheld in August 2008 by the German Supreme Court, the "Constitutional Court." "Smoking ban in public goes into effect in Syria" (21 April 2010) "China to ban smoking at indoor public places" (24 March 2011). And in Shanghai, "City looking to technology to catch smokers," says Cai Wenjun, Shanghai Daily (2 March 2012). And in Guangzhou (2 September 2012). "Medvedev to free Russia from tobacco addiction" (Pravda.Ru, 16 October 2012) ("We should ban smoking in public places and cigarettes sales on every corner. We should also ban the tobacco advertising completely and raise taxes for cigarette manufacturers to a meaningful level," Medvedev said . . . tobacco companies have doubled their sales primarily at the expense of women and, unfortunately, children") "Putin signs law to curb smoking, tobacco sales in Russia" (Reuters, Monday 25 February 2013). The law went into effect 1 June 2013, says the article "Russia smoking ban starts; 40% of country smokes" (Associated Press, 1 June 2013). The law "prohibits smoking in workplaces, schools, universities and on public transportation." Australia's Nationwide Smoking Ban (September 2013) For comprehensive country listing, see "International Public Policy Guide (Summary)." |

Examples of Smoking Ban Cities

|

Calabasas, California (23 January 2006)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (18 September 2006) Allegheny County, Penn. (September 2006) "New York City to try banning smoking in parks and beaches" (September 2010) "California Smoking Ban Said to Be Most Stringent in U.S." (22 November 2013) ("A California ordinance that prohibits smoking in residences with shared walls may be the strictest anti-smoking law in the United States . . . It covers any multi-family residence with three or more units, including condominiums, co-ops and apartments. . . . studies . . . found secondhand smoke seeps through walls, ventilation ducts and even cracks as justification for the ordinance.") |

Example of University Tobacco Ban

| Southern University (Baton Rouge, New Orleans and Shreveport) |

Example of University Tobacco Ban

| Nonsmokers Hotel, Japan: No smokers allowed on premises |

Examples of Outdoor Smoking Ban

|

Seattle City Parks Ban 17 February 2010

"Outdoor smoking bans" (Los Angeles Times, April 2010) "Supes ban smoking at most county beaches and parks" (Daily Sound, April 2010) "Portion of Walnut Creek groundbreaking secondhand smoke law takes effect Oct. 31" (California, 9 Oct 2013) ("bans smoking in all multiunit residences, all of downtown, all recreational areas and all commercially zoned properties, and in all public places," thereby enforcing the herein-cited constitutional rights in those locations, similiar to noise control ordinances) |

http://CoalitionAgainstWoodBurning.com "Wood Smoke SUCCESS STORY!" (10 September 2013) (smoke victim filed insurance claim re damages, triggering the polluter's insurance company responsibility to pay, in turn motivating the polluter to cease and desist) |

How Smoke-Free Rights Have Been Sabotaged

| 1. The first sabotage method is pushers' disregard of the law and facts herein presented, and instead, criminally fraudulently with intent to mass kill, pushing the extreme opposite notion, the maliciously false claim of a "right to smoke." Clearly, there is none. Rights are something recognized in law, and enforceable, including by a court injunction to compel respect for the violated right, e.g., the right to vote. You know you cannot get an injunction to compel some farmer to grow tobacco, some seed company to supply tobacco seeds, some building owner to store tobacco, some factory to manufacture cigarettes, pipes, cigars, etc., some trucker to deliver it, some local store to sell tobacco! Such facts are obvious, but pushers -- with intent to mass murder -- and aided and abetted by murderous media, continuingly promote the killer myth!

2. Pushers of course never mention smokers' rights to sue their pusher! nor the criminal laws and precedents enabling prosecuting pushers for poisoning and murder! 3. Pushers and their accessories never mention that far from being a right, the opposite of being a right, smoking is instead a medically recognized mental disorder. 4. Pushers never mention that poisoning the air others breathe is a criminal act. 5. A fifth technique of sabotaging the actual rights involved, is by corrupting politicians into not passing implementing statutory laws, or weak laws. That technique is a tactic from the slavery era. Slavery was primarily by tobacco growers. They have not forgotten the tactics of that era, to sabotage constitutional rights. That sabotage tactic is, to oppose passing of rights-enforcing/ implementing laws. During the slavery era, the “Freeport Doctrine" of pro-slavery Senator Stephen A. Douglas was to this effect:  Following this line of reasoning, tobacco pushers and their media and other accessories and front groups (sometimes misleadingly named as "Tea Parties") work to sabotage (a) the passing of, and (b) the enforcing of, laws implementing / enforcing the constitutional rights to pure air and to put out fires. Tobacco pusher slavers killed millions during the pre-Civil War slavery era; killing more millions, even a billion people, is OK by them! notwithstanding any laws to the contrary. Following this line of reasoning, tobacco pushers and their media and other accessories and front groups (sometimes misleadingly named as "Tea Parties") work to sabotage (a) the passing of, and (b) the enforcing of, laws implementing / enforcing the constitutional rights to pure air and to put out fires. Tobacco pusher slavers killed millions during the pre-Civil War slavery era; killing more millions, even a billion people, is OK by them! notwithstanding any laws to the contrary.

When the government enforces the constitutional rights applicable against tobacco, shows the article "State smoking ban cuts indoor air pollution 93 percent" (4 December 2011). "Michigan’s 18-month-old ban on smoking in restaurants is allowing Michigan patrons to breathe cleaner air. A recent study found a 93 percent reduction in air pollutants given off by secondhand smoke in restaurants across the state, said Teri Wilson, public health research and evaluation consultant with the tobacco section at the Michigan Department of Community Health. Heather Alberda, tobacco prevention specialist for the Ottawa County Health Department, said the study results are a win-win for consumers and for those in the food service industry." The most efficient way to enforce the rights herein shown, is not by laws targeting individuals, but by laws targeting manufacturers and sellers. For example, with respect to noisy auto boomboxes, “Roseville [Michigan] Police Chief Rick Heinz supports a ban . . . saying police cannot chase down every noisy driver. . . . [a mere anti-noise rule is] one of those things that is tough to enforce. It [solution] has to come by banning the product. Unless the car was to sit right in front of your house . . . By the time you call, the offender is gone.'”—Christy Strawser, “Fed up with boom boxes,” Macomb Daily (4 September 2007), pp 1A and 5A, at 5A. This type wisdom -- to target the manufacturers and sellers -- was known a century ago, by, e.g., Iowa, Tennessee, and Michigan, which banned cigarette manufacturing by law. (Of course, educational standards were higher back then). |

This site is sponsored as a public service by

The Crime Prevention Group

Email@TCPG