This site reprints from the pre-Civil War slavery era, abolitionist Frederick Douglass's lecture, "Unconstitutionality of Slavery." The lecture aims to show by Constitutional and legal principles, that U.S. slavery was unconstitutional. This site reprints from the pre-Civil War slavery era, abolitionist Frederick Douglass's lecture, "Unconstitutionality of Slavery." The lecture aims to show by Constitutional and legal principles, that U.S. slavery was unconstitutional.

The English King's Bench (equivalent to the U.S. Supreme Court) had declared slavery unconstitutional in 1772, in the case of Somerset v Stewart, Lofft 1-18; 11 Harg. State Trials 339; 20 Howell's State Trials 1, 79-82; 98 Eng Rep 499-510 (1772). The Somerset precedent was to be followed in the U.S.A. "because the precedent had become part of American common law."—William M. Wiecek, "Somerset's Case," Encyclopedia of the American Constitution, Leonard W. Levy and Kenneth L. Karst, eds. (New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2000), Vol 5, pp 2451-2452. Accordingly, Rep. Gerrit Smith would say of the Thirteenth Amendment: “I never liked [it]. It implies or, at least, seems to imply, that the [original] Constitution did not forbid the greatest of crimes—whereas by the canon of legal interpretation (,and no other was admissible,) it did [already] forbid it. I should [would] have preferred an Amendment, that simply disallows a Pro-Slavery interpretation of an already Anti-Slavery Constitution.”—Letter to Senator Charles Sumner (5 February 1866). But slavers were disobeying. Accordingly, based on what they were doing, Douglass said: "There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour. Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival." Others said likewise, During the pre-Civil War slavery era, a number of abolitionists wrote books or essays against slavery. They included Samuel May (1836), Salmon P. Chase (1837), George Mellen (1841), Alvan Stewart (1845), Lysander Spooner (1845), Benjamin Shaw (1846), Horace Mann (1849), Joel Tiffany (1849), William Goodell (1852), Abraham Lincoln (1854), Edward C. Rogers (1855), William E. Whiting, LL.D., et al. (1855), and Rep. Amos P. Granger (1856). They, like Douglass, showed that slavery was unconstitutional pursuant to That 1215 rights document had banned detentions without due process, e.g., charges verified by conviction in a jury trial. Slavery did not provide this due process. Wherefore, such abolitionists said it was unconstitutional—and illegal as well, pursuant to anti-kidnaping laws. Preparatory to your reading this site, reading the overview is recommended.

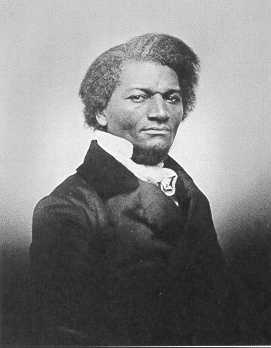

Mr. Douglass was an abolitionist, and was a particular expert, having himself escaped from slavery (1838). This site reprints his 26 March 1860 lecture, "Unconstitutionality of Slavery." It provides in a brief overview, some of the many principles of constitutional law making slavery unconstitutional. He is explaining, verbally, points of constitutional law, obscure, abstruse, difficult, esoteric, constitutional law. Normally, as in law or graduate school, this type presentation requires the audience As Douglass's 1860 audience of laymen were not law students nor scholars, nor even had a copy by which to follow along, they did not have that opportunity. Douglass must (and does) therefore in some detail, lay the precise, detailed, obscure, foundation, by way of introducing the subject. He must proceed slowly, meticulously, laboriously, so that the audience, some of whom were hostile and heckling, would understand. That audience did not have your advantage of immediate access to the several constitutional law books reprinted in this series. In that era, Americans were traveling to England and Scotland, before the War, seeking their support. Such Americans naturally presented their own legal opinions on slavery, as to whether it was or was not constitutional, attempting to persuade the British to whatever was their individual view. On this constitutional law issue, you'll note that a speaker (George Thompson) taking the 'slavery is constitutional' view had recently [27 January 1860] spoken in that area, at the City Hall. One issue was whether the U.S. should (or would) be dissolved, broken up, as hopelessly pro-slavery. This year, 1860, is an election year. It is still early, on 26 March 1860, in the Election-1860 campaign season and calendar. Lincoln's nomination at the then-future 16-19 May 1860 Republican Convention was then unknown. Even less knowable, even inconceivable, was his then-far-future November 1860 win. These events were then, March 1860, UNKNOWN as not yet having occurred. Interest in Douglass' views was heightened, as a pro-slavery candidate would likely foreseeably once again win. The winner, next President, would foreseeably be Sen. Stephen O. Douglas. It was that Senator who was expected to be the pro-slavery nominee to run against William H. Seward, the then-anticipated Republican nominee. Audiences of that era were prone to heckle or applaud depending on their reactions. While some in the lay audience evidently were Frederick Douglass supporters, others were not, especially as his viewpoint was (as now), generally unknown or disbelieved. The speech as originally published contains hints of audience reactions, outbursts, during the course of the presentation! In this context, Mr. Douglass is now responding to the prior speaker's claims, and presenting the generally unknown 'slavery is unconstitutional' position, as per the data here being reprinted, from that era. A fundamental reason that this type anti-slavery analysis is nowadays generally unknown is that the pro-Southern viewpoint (their pretense that slavery was constitutional) is the one most presented in textbooks, due to Southerners' ultra-disproportionate influence in the textbook market. Douglass first responds to criticisms of his abolitionist position, including criticisms made at the area City Hall by the recent speaker (George Thompson) there, having lambasted Douglass personally, ad hominem, for his having supported the 'slavery is already unconstitutional,' position, pre-13th Amendment. Douglass admits that when he had first escaped slavery, he had himself been provided the standard Confederate disinformation claim that slavery was constitutional. Douglass explains his subsequent discovering the real truth. This discovery led him to reverse his prior disinformed view, p 18. This speech revealing the real truth (slavery has always been unconstitutional) is going to be a tense situation, so Douglass must use care. He must use references with which the audience WOULD be familiar. This would include such references as Douglass rebuts the pro-slavery allegations on key issues, e.g., And in doing so, he must use some humor, as any professional speaker would in such a situation. This will be an interesting time for both the speaker and audience! Heckling can be expected! and must be defused, for understanding of the generally unknown, still unknown, 'slavery is already unconstitutional' position to occur. To get this impact, read the speech aloud, yourself, slowly, emphasizing aloud each key point; if need be, have another person do likewise. This material is not easy even now. Give yourself fair chance to follow, grasp, comprehend, the difficult concepts, to reverse the disinformation you yourself have perhaps been taught via the above-cited Southern view disproportionately disinforming modern textbooks. “Partem aliquam recte intelligere nemo potest, antequam totum, iterum atque iterum, periegerit.” No one can rightly understand any part until he has read the whole again and again. After reading, feel free to join the discussion forum. |

Lecture Delivered in Glasgow, Scotland 26 March 1860 by Frederick Douglass (London: William Tweedie, Pub, 1860)

I read with deep interest the speeches made recently at a meeting called to sympathise with and to assist that faithful champion of the cause of my enslaved fellow-countrymen, Dr. [George B.] Cheever.

I have also read of another meeting in your city [Glasgow], having reference to the improvement and elevation of the people of Africa—having reference to the cultivation of cotton and the opening up of commerce between this and that land. All these movements are in the right direction. I accept them and hail them as signs of "the good time coming," when Ethiopia "shall stretch out her hands to God [Psalm 68:31]" in deed and in truth. There have been, also, other meetings in your city since it was my privilege last to address you. I have read with much care a speech recently delivered [by George Thompson on 27 Jan 1860] in the City Hall. It is published in one of your most respectable journals. The minuteness and general shading of that report convince me that the orator [George Thompson] was his own reporter. At any rate, there is but little evidence or few marks of its having been tampered with by any than one exceedingly friendly to the sentiments it contains. On some accounts I read that speech with regret; on others with much satisfaction. I was certainly pleased with the evidence it afforded that the orator [George Thompson] has largely recovered his long-lost health, and much of his wonted eloquence and fire; but my chief ground of satisfaction is that its delivery—perhaps I ought to say its publication—for I would not have noticed the speech had it not been published in just such a journal as that in which it was published—furnishes an occasion for bringing before the friends of my enslaved people one phase of the great struggle going on between liberty and slavery in the United States which I deem important, and which I think, before I get through, my audience will agree with me is a very important phase of that struggle. The North British Mail honored me with a few pointed remarks in dissent from certain views held by me on another occasion in this city; but as it rendered my speech on that occasion very fairly to the public, I did not feel at all called upon to reply to its strictures. The case is different now. I am brought face to face with two powers. I stand before you under the fire of both platform and press. Not to speak, under the circumstances, would subject me and would subject my ['slavery is already unconstitutional'] cause to misconstruction. You might be led to suppose that I had no reasons for the ground [his saying slavery is already unconstitutional] that I occupied here when I spoke in another place before you. Let me invite your attention, I may say your indulgent attention, to this very interesting phase of the question of slavery in the United States. My assailant [George Thompson], as he had a perfect right to do—that is, if he felt that that was the best possible service he could do to the cause of American slavery—under advertisement to deliver an "anti-slavery lecture"—a lecture on the present aspect of the anti-slavery movement in America—treated the citizens of Glasgow to an "anti-Douglass" lecture. He seemed to feel that to discredit me was an important work, and therefore he came up to that work with all his wonted power and eloquence, proving himself to be just as powerful and skillful a debater, in all its arts, high and low, as long practice, as constant experience could well fit a man to be. I award to the eloquent lecturer [George Thompson], as I am sure you do, all praise for his skill and ability, and fully acknowledge his many valuable services, in other [prior] days, to the anti-slavery cause both in England and America. We all remember how nobly he confronted the Borthwicks and the Breckenridges in other days, and vanquished them. These victories are safe; they are not to be forgotten. They belong to his past, and will render his name dear and glorious to aftercoming generations. He then enjoyed the confidence of many of the most illustrious philanthropists that Scotland has ever raised up. He had at his back, at those times, the Wardlaws, the Kings, the Heughs, and Robsons——men who are known the world over for their philanthropy, for their Christian benevolence. He was strong in those days, for he [then] stood before the people of Scotland as the advocate of a great and glorious cause [anti-slavery]——he stood up for the dumb, for the down-trodden, for the outcasts of the earth, and not for a mere party, not for the mere sect whose mischievous and outrageous opinions he now consents to advocate in your hearing. When in Glasgow a few weeks ago, I embraced the occasion to make a broad statement concerning the various plans proposed for the abolition of slavery in the United States, but I very frankly stated with what I agreed and from what I differed; but I did so, I trust, in a spirit of fair dealing, of candor, and not in a miserable, man-worshipping, and mutual-admiration spirit, which can do justice only to the party with which it may happen to go for the moment. One word further. No difference of opinion, no temporary alienations, no personal assaults shall ever lead me to forget that some who, in America, have often made me the subject of personal abuse, are at the same time, in their own way, earnestly working for the abolition of slavery. They [abolitionists, "Garrisonians," with the opposite constitutional interpretation] are men

In regard to the speaker to whom I am referring [George Thompson], and who by the way is, perhaps the least vindictive of his party, I shall say that I cannot praise his speech, for it is needlessly, or was needlessly personal calling me by name over, I think, fifty times, and dealing out blows upon me as if I had been savagely attacking him. In character and manliness that speech was not only deficient, I think, but most shamefully one-sided; and while it was remarkably plausible, and well calculated to catch the popular ear, which could not well discriminate between what was fact and what was fiction in regard to the subject then discussed, I do not hesitate to pronounce that speech [alleging that U.S. slavery is constitutional]

On very many accounts [for many reasons], he who stands before a British audience to denounce any thing peculiarly American in connection with slavery has a very marked and decided advantage. It is not hard to believe the very worst of any country where a system like slavery has existed for centuries. This feeling towards America, and towards every thing American, is very natural and very useful. I refer to it now not to condemn it; but to remind you

My assailant largely took advantage of this noble British feeling in denouncing the constitution and Union of America. He knew how deep and intense was your hatred of slavery. He knew the strength of that feeling, and the noble uses to which it might have been directed. I know it also, but I would despise myself if I could be guilty of

I have often felt how easy it would be, if one were so disposed, to make false representations of things as they are in America; to disparage whatever of good might exist there, or shall exist there, and to exaggerate whatever is bad in that country. I intend to show that this very thing was done by the speaker to whom I have referred; that his speech was calculated to convey impressions and ideas totally, grossly, outrageously at variance with truth concerning the constitution and Union of the American States. You will think this very strong language. I think so too; and it becomes me to look well to myself in using such language, for if I fail to make out my case, I am sure there are parties not a few who will see that fair play is done on the other side. [!!!] But I have no fear at all of inability to justify what I have said; and if any friend of mine was led to doubt, from the confident manner in which I was assailed, I beg that such doubt may now be put aside until, at least, I have been heard. I will make good, I promise you, my entire characterisation of that speech. Reading speeches [Ed. Note: that night, as distinct from his normal extemporaneous style] is not my forte, and you will bear with me until I get my harness on. I have fully examined my ground, and while I own myself nothing in comparison with my assailant in point of [oratorical] ability, I have no manner of doubt as to the rectitude of the position I occupy on the question. Now, what is that question? Much will be gained at the outset if you fully and clearly understand the real question under discussion—the question and difference between us. Indeed, nothing can be understood till this is understood. Things are often confounded and treated as the same for no better reason than that they seem alike or look alike, and this is done even when in their nature and character they are totally distinct, totally separate, and even opposed to each other. This jumbling up of things is a sort of dust-throwing which is often indulged in by small men who argue for victory rather than for truth. Thus, for instance, the American government and the American constitution are often spoken of in the speech to which I refer as being synonymous—as one and the same thing; whereas, in point of fact, they are entirely distinct from each other and totally different. In regard to the question of slavery, certainly they [government; Constitution] are different from each other; they are as distinct from each other as the compass is from the ship—as distinct from each other as the chart is from the course which a vessel may be sometimes steering. They are not one and the same thing. If the American government has been mean, sordid, mischievous, devilish, it is no proof whatever that the constitution of government has been the same. And yet, in the speech to which some of you listened, these sins of the government or administration of the government were charged directly upon the constitution and Union of the states. What, then, is the question? I will state what it is not. It is not —all these points may be true or they may be false, they may be accepted or they may be rejected, without at all affecting the question at issue between myself and the "City Hall" [Ed. Note: allusion to prior speaker, George Thompson]. The real question between the parties differing at this point in America may be fairly stated thus:—"Does the United States constitution guarantee to any class or description of people in that country the right to enslave or hold as property any other class or description of people in that country?" The second question is:—"Is the dissolution of the Union between the Slave States and the Free States required by fidelity to the slaves or the just demands of conscience;?" Or, in other words, "Is the refusal to exercise the elective franchise or to hold office in America, the surest, wisest, and best mode of acting for the abolition of slavery in that country?" To these questions the Garrisonians in America answer, "Yes." They hold that

I [and others], on the other hand,

This is the issue plainly stated, and you shall judge between us. Before we examine into the disposition, tendency, and character of the constitution of the United States, I think we had better ascertain what the constitution itself is. Before looking at what it means, let us see what it is. For here, too, there has been endless dust-throwing on the part of those opposed to office. What is the constitution? It is no vague, indefinite, floating, unsubstantial something, called, according to any man's fancy, now a weasel and now a whale. But it is something substantial. It is a plainly written document; not in Hebrew nor in Greek, but in English, beginning with a preamble, fitted out with articles, sections, provisions, and clauses, defining the rights, powers, and duties to be secured, claimed, and exercised under its authority. It is not even like the British constitution. It is not made up of enactments of parliament, decisions of courts, and the established usages of the government. The American constitution is a written instrument, full and complete in itself. No court, no congress, no legislature, no combination in the country can add one word to it, or take one word from it. [Reference]. It is a thing in itself; complete in itself; has a character of its own; and it is important that this should be kept in mind as I go on with the discussion. It is a great national enactment, done by the people, and can only be altered, amended, or changed in anyway, shape, or form by the people who enacted it. I am careful to make this statement here; in America it would not be necessary. It would not be necessary here if my assailant had shown that he had as sincere and earnest a desire to set before you the simple truth, as he has shown to vindicate his particular sect in America. Again, it should be borne in mind that the mere text of that constitution—the text and only the text, and not any commentaries or creeds written upon [about] the text—is the constitution of the United States. It should also be borne in mind that the intentions of those who framed the constitution, be they good or bad, be they for slavery or against slavery, are to be respected so far, and so far only, as they have succeeded in getting these intentions expressed in the written instrument itself. This is also important.

It would be the wildest of absurdities, and would lead to the most endless confusions and mischiefs, if, instead of looking to the written instrument itself for its meaning, it were attempted to make us go in search of what could be the secret motives and dishonest intentions of some of the men who might have taken part in writing or adopting it. It was what they said that was adopted hy the people; not what they [the Constitutional Convention delegates] were ashamed or afraid to say, or really omitted to say. It was not what they [the Constitutional Convention delegates] tried, nor what they concealed; it was what they wrote down, not what they kept back, that the people adopted. It was only what was declared upon its face that was adopted—not their secret understandings, if there were any such understandings. Bear in mind, also, and the fact is an important one, that the framers of the constitution, the men who wrote the constitution, sat with closed doors in the city of Philadelphia while they wrote it. They sat with closed doors, and this was done purposely, that nothing but the result, the pure result of their labours should be seen, and that that result might stand alone and be judged of on its own merits, and adopted on its own merits, without any influence being exerted upon them by the debates. It should also be borne in mind, and the fact is still more important, that the debates in the convention that framed the constitution of the United States, and by means of which a pro-slavery interpretation is now attempted to be forced upon that instrument, were not published until nearly thirty years after the constitution of the United States; so that the men who adopted [later ratified] the constitution could not be supposed to understand the [prior] secret underhand [unknown and unpublished] intentions that might have controlled the actions of the convention in making it. These debates were purposely kept out of view, in order that the people might not adopt [vote for] the secret motives, the unexpressed intentions of anybody, but simply the text of the paper itself. These debates form no part of the original agreement, and, therefore, are entitled to no respect or consideration in discussing what is the character of the constitution of the United States. I repeat, the paper itself and only the paper itself, with its own plainly written purposes, is the constitution of the United States, and it must stand or fall, flourish or fade, on its own individual and self-declared purpose and object. Again, where would be the advantage of a written constitution, I pray you, if, after we have it written, instead of looking to its plain, common sense reading, we should go in search of its meaning to the secret intentions of the individuals who may have had something to do with writing the paper? What will the people of America a hundred years hence, care about the intentions of the men who framed the constitution of the United States? These men were for a day—for a generation, but the constitution is for ages; and, a hundred years hence, the very names of the men who took part in framing that instrument will, perhaps, be blotted out or forgotten. Whatever we may owe to the framers of the constitution, we certainly owe this to ourselves, and to mankind, and to God, that we maintain the truth of our own language, and do not allow villainy, not even the villainy of slaveholding—which, as John Wesley says, is the sum of all villainies—to clothe itself in the garb of virtuous language, and get itself passed off as a virtuous thing, in consequence of that language. We owe it to ourselves to compel the devil to wear his own garments; particularly in law we owe it to ourselves to compel wicked legislators, when they undertake a malignant purpose in innocent and benevolent language, we owe it to ourselves that we circumvent their wicked designs to this extent, that if they want to put it to a bad purpose, we will put it to a good purpose. Common sense, common justice, and sound rules of interpretation all drive us to the words of the law for the meaning of the law. [Reference]. The practice of the American government is dwelt upon with much fervour as conclusive as to the slaveholding character of the American constitution. This is really the strong point, and the only strong point, made in the speech in the City Hall; but, good as this argument is [superficially], it is not conclusive. A wise man has said that few people are found better than their laws, but many have been found worse; and the American people are no exception to this rule. I think it will be found they are much worse than their laws, particularly their constitutional laws. It is just possible the people's practice may be diametrically opposed to

Our blessed Saviour when upon earth found the traditions of men taking the place of the law and the prophets. [Reference]. The Jews asked him why his disciples ate with unwashed hands, and he brought them to their senses by telling them that they had made void the law by their traditions. [Matt. 15:1-6; Mark 7:1-13]. Moses, on account of the hardness of the hearts of men, allowed the Jews to put away their wives; but it was not so at the beginning. [Matt. 19:8]. The American people, likewise,

While the one is good, the other is evil; while the one is for liberty, the other is in favour of slavery; the practice of the American government is one thing, and the character of the constitution of the government is quite another and different thing. After all, Mr. Chairman, the fact that my opponent thought it necessary to go outside of the constitution to prove it pro-slavery, whether that going out is to the practice of the government, or to the secret intentions of the writers of the paper itself, the fact that men do go out is very significant. It is an admission that the thing they look for is not to be found where only it ought to be found if found at all, and that is, in the written constitution itself. If it is not there, it is nothing to the purpose if it is found any where else; but I shall have more to say on this point hereafter. The very eloquent lecturer at the City Hall doubtless felt some embarrassment from the fact that he had literally to give the constitution a pro-slavery interpretation; because on its very face it conveys an entirely opposite meaning. He thus sums up what he calls the slaveholding provisions of the constitution, and I quote his words:—

Now, Mr. President, and ladies and gentlemen, any man reading this statement, or hearing it made with such a show of exactness, would unquestionably suppose that the speaker or writer had given the plain written text of the constitution itself. I can hardly believe that that gentleman intended to make any such impression on his audience, and yet what are we to make of it, this circumstantial statement of the provisions of the constitution? How can we regard it? How can he be screened from the charge of having perpetrated a deliberate and point blank misrepresentation? That individual [George Thompson] has seen fit to place himself before the public as my opponent. Well, ladies and gentlemen, if he had placed himself before the country as an enemy, I could not have desired him—even an enemy—to have placed himself in a position so false, and to have committed himself to statements so grossly at variance with the truth as those statements I have just read from him. Why did he not read the constitution to you? Why did he read that which was not the constitution-—for I contend he did read that which was not the constitution. He pretended to be giving you chapter and verse, section and clause, paragraph and provision, and yet he did not give you a single clause or single paragraph of that constitution.

You can hardly believe it, but I will make good what I say, that, though reading to you article upon article, as you supposed while listening to him, he did not read a word from the constitution of the United States; not one word.

You had better not applaud until you hear the other side and what are the real words of the constitution. [!!!] Why did he not give you the plain words of the constitution? He can read; he had the constitution before him; he had there chapter and verse, the places where those things he alleged to be found in the constitution were to be found. Why did he not read them? Oh, Sir, I fear that that gentleman knows too well why he did not. I happen to know that there are anywhere to be found in that constitution. You can hardly think a man would stand up before an audience of people in Glasgow, and make a statement so circumstantial, with every mark of particularity, to point out to be in the constitution what is not there. You shall see a slight [huge!!] difference in my manner of treating that subject and that which my opponent has thought fit, for reasons satisfactory to himself, to pursue. What he withheld, that I will spread before you; what he suppressed, I will bring to light; and what he passed over in silence, I will proclaim. Here then are the several provisions of the constitution to which reference has been made. I will read them word for word, just as they stand in the paper, in the constitution itself.

Here then are the provisions of the constitution which the most extravagant defenders of slavery have ever claimed to guarantee the right of property in man. These are the [sole] provisions which have been [fraudulently] pressed into the service of the human fleshmongers of America; let us look at them just as they stand, one by one. You will notice there is

I deny utterly that these provisions of these constitution guarantee, or were intended to guarantee, in any shape or form, the right of property in man in the United States. But let us grant, for the sake of argument, that the first of these provisions, referring to the basis of representation and taxation, does refer to slaves. We are not compelled to make this admission, for it might fairly apply, and indeed was intended to apply, to aliens and others, living in the United State, but who were not naturalised. But giving the provision the very worst construction—that it applies to slaves—what does it amount to? I answer—and see you bear it in mind, for it shows the disposition of the constitution to slavery—I take the very worst aspect, and admit all that is claimed or that can be admitted consistently with truth; and I answer that this very provision, supposing it refers to slaves, is in itself a downright disability imposed upon the slave system of America, one which deprives the slaveholding States of at least two-fifths of their natural basis of representation. A black man in a free State is worth just two-fifths more than a black man in a slave State, as a basis of political power under the constitution. Therefore, instead of encouraging slavery, the constitution encourages freedom, by holding out to every slaveholding State the inducement of an increase of two-fifths of political power by becoming a free State. So much for the three-fifths clause; taking it at its worst, it still leans to freedom, not to slavery; for be it remembered that, the constitution nowhere forbids a black man to vote. No "white," no "black," no "slaves," no "slaveholder"—nowhere in the instrument are any of these words to bo found, I come to the next, that which it is said guarantees the continuance of the African slave-trade for twenty years [i.e., 1788-1808]. I will also take that for just what my opponent alleges it to have been, although the constitution does not warrant any such conclusion. But, to be liberal [to Thompson and similar-minded abolitionists], let us suppose it did, and what follows? Why, this—that this part of the constitution of the United States expired by its own limitation no fewer than fifty two years ago. My opponent is just fifty-two years too late in seeking the dissolution of the Union on account of this clause, for it expired as far back as 1808. He might as well attempt to break down the British parliament and break down the British constitution, because, three hundred years ago, Queen Elizabeth [1558-1603] granted to Sir John Hawkins the right to import Africans into the colonies in the West Indies. This ended some three hundred years ago; ours ended only fifty-two years ago, and I ask is the constitution of the United States to be condemned to everlasting infamy because of what was done fifty-two years ago?

But there is still more to be said about this provision of the constitution.

At the time the constitution was adopted, the slave trade was regarded as the jugular vein of slavery itself, and it was thought that slavery would die with the death of the slave trade.

No less philanthropic, no less clear-sighted men than your [William] Wilberforce and [Thomas] Clarkson [prominent British abolitionists] supposed [assumed] that the abolition of the slave-trade would be the abolition of slavery. Their theory was—cut off the stream, and of course the pond or lake would dry up: cut off the stream [of slaves] flowing out from Africa, and the slave-trade in America and the colonies would perish.

The fathers who framed the American constitution supposed [assumed likewise] that in making provision for the abolition of the African slave-trade they were making provision for the abolition of slavery itself, and they incorporated this clause in the constitution, not to perpetuate the traffic in human flesh, but to bring that unnatural traffic to an end.

Outside of the Union the slave-trade could be carried on to an indefinite period; but the men who framed the constitution, and who proposed its adoption, said to the slave States,—If you would purchase the privileges of this Union, you must consent that the humanity of this nation shall lay its hand upon this traffic at least in twenty years after the adoption of the constitution. So much for the African slave-trade clause. If [and Mr. Douglass here looked in the direction of Mr. Robert Smith, president of the Scottish Temperance [Anti-Alcoholism] League]—if you can't get a man to take the pledge that he will stop drinking liquor today, it is something if you will get him to promise to take it [the pledge] tomorrow, and if the men who made the American constitution did not bring the African slave-trade to an end instantly, it was something to succeed in bringing it to an end in twenty years.

I now go to [discuss] the slave insurrection clause, though, in truth, there is no such clause in the constitution.

But, suppose that this clause in the constitution refers to the abolition or rather the suppression of

I hold that the right to suppress an insurrection carries with it also the right to determine by what means the insurrection shall be suppressed; and, under an anti-slavery administration, were your humble servant [Ed. Note: or any future elected abolitionist] in the presidential chair of the United States, which in all likelihood never will be the case [Ed. Note: Neither Abraham Lincoln nor his November election were foreseen], and were an insurrection to break out in the southern states among the slave inhabitants, what would I [he] do in the circumstance, I [he] would suppress the insurrection, and I [he] should choose my own way of suppressing it; I [he] should have the right, under the constitution, to my [his] own manner of doing it.

If I [he] could make out, as I believe I [he] could, that slavery is itself an insurrection—that it is an insurrection by one party in the country [Ed. Note: soon-to-be-called "secession"] against the just rights of another part of the people in the country, a constant invitation to insurrection, a constant source of danger—as the executive officer of the United States it would be my duty not only to put down the insurrection, but to put down the cause of the insurrection.

I [he] would have no hesitation at all in supporting the constitution of the United States in consequence of its provisions. The constitution should be obeyed, should be rightly obeyed. We should say to the slaves, and we should say to their masters,

In a word, with regard to putting down insurrection, I [he] would just write a proclamation [Ed. Note: an Emancipation Proclamation, under the 'war power' clause, perhaps?!], and the proclamation would be based upon the old prophetic model of proclaiming liberty throughout all the land, to all the inhabitants thereof. [Lev. 25:10].

But there is one other provision called the "Fugitive Slave Provision." It is called so by those who wish it to subserve the interests of slavery.

"On the 27th of September, Mr. Butler and Mr. Pinckney, two delegates from the state of South Carolina, moved that the constitution should require fugitive slaves and servants to be delivered up like criminals, and after a discussion on the subject, the clause as it stands in the constitution was adopted.

"After this, in conventions held in the several States to ratify the constitution, the same meaning was attached to the words.

"For example, Mr. Madison, (afterwards President) in recommending the, constitution to his constituents, told them that this clause would secure them their property in slaves." I must ask you to look well to the statement.

Upon its face it would seem to be a full and fair disclosure of the real transaction it professes to describe; and yet I declare unto you, knowing as I do the facts in the case, that I am utterly amazed, utterly amazed at the downright UNTRUTH which that very simple, plain statement really conveys to you about that transaction.

I dislike to use this very strong lan-

Under these fair-seeming words now quoted, I say there is downright untruth conveyed. The man who could make such a statement may have all the craftiness of a lawyer, but I think he will get but very little credit for the candour of a Christian.

What could more completely destroy all confidence than the making of such a statement as that!

The case which he describes is entirely different from the real case as transacted at the time.

Mr. Butler and Mr. Pinckney did indeed bring forward a proposition after the convention had framed the constitution, a proposition for the return of fugitive slaves to their masters precisely as criminals are returned.

And what happened?

Mr. Thompson—oh! I beg pardon for calling his name—tells you that after a debate it was withdrawn, and the proposition as it stands in the constitution was adopted.

He does not tell you what was the nature of the debate. Not one word of it. No; it would not have suited his purpose to have done that. It would have been against his side of the question to have done that.

I will tell you what was the purport of that debate.

After debate and discussion the provision as it stands was adopted. The purport of the provisions as brought forward by Mr. Butler and Mr. Pinckney was this:

Very well, what happened?

The proposition [proposed pro-slavery clause] was met by a storm of opposition in the convention; members rose up in all directions saying that they had no more business to catch slaves for their masters than they had to catch horses for their owners—that they would not undertake any such thing,

and the convention instructed a committee to alter that provision and the word "servitude," so that it might apply NOT to slaves, but to freemen—to persons [apprentices, etc., under that former system, paid wages in advance who might then abscond] bound to serve and labour, and not to slaves.

And thus far it seems that Mr. Madison, who was quoted so triumphantly, tells us in these very Madison Papers that that word was struck out from the constitution, because it applied to slaves and not to freemen, and that the [constitutional] convention [delegates] refused to have that word in the constitution, simply because they did not wish, and would not have [tolerate] the idea that there could be property in men in that instrument.

These are Madison's own words, so that he can be quoted on both sides.

But it may be asked, if the clause does not apply to slaves, to whom does it apply? It says—

To whom does it apply if not to slaves?

I answer that it applied at the time of its adoption to a [then] very numerous class of persons in America; and I have the authority of no less a person than Daniel Webster [1782-1852] that it was intended to apply to that class of men—a class of persons known in America as "Redemptioners."

There was quite a number of them at that day, who had been taken to America precisely as coolies have been taken to the West Indies. They entered

Why, sir, due!

In the first place this very clause of that provision makes it utterly impossible that it can apply to slaves. There is nothing due from the slave The thing [wording] implies an arrangement, an understanding, by which, for an equivalent, I will do for you so much, if you will do for me, or have done for me, so much. The constitution says he will be delivered up to whom any service or labour shall be due.

Due! A slave owes nothing to any master; he can owe nothing to any master. In the eye of the [Ed. Note: unconstitutional and/or non-extant Southern] law he is a chattel personal, to all intents, purposes, and constructions whatever. Talk of a [chattel] horse owing something to his master, or a sheep, or a wheel-barrow! Perfectly ridiculous! The idea that a slave can owe anything!

I tell you what I would do if I were a judge; I could do it perfectly consistently with the character of the constitution. I have a proneness to liken myself to great people—to persons high in authority. But if I were a judge, and a slave was brought before me under this provision of the constitution, and the master should insist upon my sending him back to slavery, I should inquire [Ed Note: as had Vermont Judge Harrington] how the slave was bound to serve and labour for him. I would point him to this same constitution, and tell him that I read in that constitution the great words of your own Magna Charta:— or property without the process of law," and I ought to know by what contract, how this man contracted an obligation, or took upon himself to serve and labour for you. And if he could not show that, I should dismiss the case and restore the man to his liberty. And I would do quite right, according to the constitution. [Reference]. I admit nothing in favour of slavery when liberty is at stake; when I am called upon to argue on behalf of liberty I will range throughout the world, I am at perfect liberty by forms of law and by the roles of hermeneutics to range through the whole universe of God in proof of an innocent purpose, in proof of a good thing; but if you want to prove a bad thing, if you want to accomplish a bad and violent purpose, you must show it is so named in the bond. This is a sound legal rule. Shakespeare noticed it as an existing rule of law in his "Merchant of Venice"; "a pound of flesh, but not one drop of blood." The law was made for the protection of labour; not for the destruction of liberty; and it is to be presumed on the side of the oppressed. The [earlier-cited] speaker at the City Hall laid down some rules of legal interpretation. These rules send us to the history of the law for its meaning. I have no objection to this course in ordinary cases of doubt, but where human liberty and justice are at stake, the case falls under an entirely different class of rules. There must be something more than history, something more than tradition, to lead me to believe that law is intended to uphold and maintain wrong. The Supreme Court of the United States lays down this rule, and it meets the case exactly: The same court says that the language of the law must be construed strictly in favour of justice and liberty; and another rule says, where the law is ambiguous and susceptible of two meanings, the one making it accomplish an innocent purpose, and the other making it accomplish a wicked purpose, we must in every case adopt that meaning which makes it accomplish an innocent purpose.

These are just the rules we like to have applied to us as individuals to begin with. We like to be assumed to be honest and upright in our purpose until we are proved to be otherwise, and the law is to be taken precisely in the same way. We are to assume it is fair, right, just, and true, till proved with irresistible power to be on the side of wrong.

Now, sir, a case like this occurred in Rhode Island some time ago. The people there made a law that no negro should be allowed to walk out after nine o'clock at night without a lantern. They were afraid the negro might be mistaken for somebody. The negroes got lanterns and walked after nine at night, but they forgot [!!!] to put candles in them. They were arrested and brought before a court of law. They had been found after nine at night, it had been proved against them that they were out with lanterns to be sure, but without a candle.

But the judge said this was a law against the natural rights of man, against natural liberty, and that this law should be construed strictly. These men had complied with the plain reading of the law, and they must be dismissed [released].

The judge in that case did perfectly right. The legislature had to pass another law, that no negro should be out after nine without a lantern and a candle in it. The negroes got candles, but forgot to light them. [!!] They were arrested again, again tried, and with a similar result.

There was then another law passed, that the negroes should not walk out after nine at night without lanterns, with candles in them, and the candles lighted. And if I had been a negro at that time in Rhode Island, I would have got a dark lantern and walked out.

Laws to sustain a wrong of any kind must be expressed with irresistible clearness; for law, be it remembered, is not an arbitrary rule of arbitrary mandate, and it has a purpose, a character in itself, a purpose of its own. Blackstone defines it as "a rule of the supreme power of the state;" but he does not stop there—he adds, "commanding that which is right, and forbidding that which is wrong"—that is law.

It would not be law if it commanded that which was wrong, and forbade that which was right in itself. It is necessary it should be on behalf of right. [Reference].

There is another law [rule] of legal interpretation, which is, that the law is to be understood in the light of the objects sought for by the law, or sought in the law

The [preamble] objects here set forth are six in number. "Union" is one, not slavery; union is named as one of the objects for which the constitution was framed, and it is one that is very excellent; it is quite incompatible with slavery. "Defence" is another; "welfare" is another; "tranquillity" is another; "justice" and "liberty" are the others. Slavery is not among them; the objects are union, defence, welfare, tranquillity, justice, and liberty. Now, if the two last—to say nothing of the defence—if the two last purposes declared were reduced to practice, slavery would go reeling to its grave as if smitten with a bolt from heaven. Let but the American people be true to their own constitution, true to the purposes set forth in that constitution, and we will have no need of a dissolution of the Union—we will have a dissolution of slavery all over that country. But it has been said that negroes are not included in the benefits sought under this [preamble] declaration of purposes. Whatever slave-holders may say, I think it comes with ill grace from abolitionists to say the negroes in America are not included in this declaration of purposes. The negroes are not included! Who says this? The constitution does not say they are not included, and how dare any other person, speaking for the constitution, say so? The constitution says "We the people;" the language is "we the people;" not we the white people, not we the citizens, not we the privileged class, not we the high, not we the low, not we of English extraction, not we of French or of Scotch extraction, but "we the people;" not we the horses, sheep, and swine, and wheelbarrows, but we the human inhabitants; and unless you deny that negroes are people, they are included within the purposes of this government. They were there, and if we the people are included, negroes are included; they have a right, in the name of the constitution of the United States, to demand their liberty. This, I undertake to say, is the conclusion of the whole matter—

It is by this mean, contemptible, under-hand way of working out the pro-slavery character of the constitution, that the thing is accomplished, and in no other way. The first utterance of the instru- ment itself [the preamble] is gloriously on the side of liberty, and diametrically opposed to the thing called slavery in the United States. The constitution [and bill of rights]

It was in consequence of this writ [of habeas corpus]—a writ which forms a part of the constitution of the United States—that England herself is free from man-hunters to-day; for in 1772 slaves were hunted here in England just as they are in America, and the British constitution was supposed to favour the arrest, the imprisonment, and re-capture of fugitive slaves. But Lord Mansfield, in the case of Somerset, decided that no slave could breathe [legally be held] in England. We have the same writ, and let the people in Britain and the United States stand as true to liberty as the constitution is true to liberty, and we shall have no need of a dissolution of the Union. But to all this it is said that the practice of the American people is against my view. I admit it. They have given the constitution a slaveholding interpretation. I admit it. And I go with him who goes furthest in denouncing these wrongs, these outrages on my people. But to be consistent with this logic, where does it lead? Because the practice of the American people has been wrong, shall we therefore denounce the constitution? The same logic would land the man of the City Hall [the previously-cited speaker] precisely where the same logic has landed some of his friends in America—in the dark, benighted regions of infidelity itself. [They claim that] The constitution is pro-slavery, because men have interpreted it to be pro-slavery, and practice upon it as if it were pro-slavery. [Reference]. The very same thing, sir, might be said of the Bible itself; for in the United States men have [falsely] interpreted the Bible against liberty. They have [falsely] declared that Paul's epistle to Philemon is a full proof for the enactment of that hell-black Fugitive Slave Bill which has desolated my people for the last ten years in that country. They have declared [falsely] that the Bible sanctions slavery. What do we do in such a ease? What do you do when you are told [falsely] by the [demonized] slaveholders of America that the Bible sanctions slavery? Do you go and throw your Bible into the fire? Do you sing out, "No Union with the Bible!"? Do you declare that a thing is bad because it has been misused, abused, and made a bad use of? Do you throw it away on that account? No! [Reference]. You press it to your bosom all the more closely; you read it all the more diligently; and prove from its pages that it is on the side of liberty—and not on the side of slavery. So let us do so with the constitution of the United States. But this logic would carry the orator of the City Hall a step or two further; it would lead him to break down the British constitution. I believe he is not only a Protestant, but he is a Dissenter; and if he is opposed to the American constitution because certain evils exist therein, could he well oppose all the other constitutions? But I must beg pardon for detaining you so long—I must bring my remarks speedily to a close. Let me make a statement. It was said to you that the Southern States had increased from 5 up to 15. What is the fact with reference to this matter? Why, my friends, the slave States in America have increased just from 12 up to 15. But the other statement was not told you. It is this: the Free States have increased from 1 up to 18. That fact was not told. No; I suppose it was expected I would come back and tell you all the truth. It takes two men to tell the truth any way. The dissolution of the Union, remember, that was clamoured for that night, would not give the Northern states one single advantage over slavery that it does not now possess. Within the Union we have a firm basis of opposition to slavery. It is opposed to all the great objects of the constitution. The dissolution of the Union is not only an unwise but a cowardly proposition. Dissolve the Union! For what? Tear down the house in an instant because a few slates have been blown off the roof? There are 350,000 slaveholders in America, and 26 millions of free white people. Must these 26 millions of people break up their government, dissolve their Union, burn up their constitution—for what? to get rid of the responsibility of holding slaves? But can they get rid of responsibility by that? Alas no! The recreant husband may desert the family hearth, may leave his starving children, and you may place oceans, islands, and continents between him and his; but the responsibility, the gnawing of a guilty conscience must follow him wherever he goes. If a man were on board of a pirate ship, and in company with others had robbed and plundered, his whole duty would not be performed simply by taking to the long boat and singing out, "No union with pirates!" His duty would be to restore the stolen property. The American people in the Northern States have helped to enslave the black people. Their duty will not have been done till they give them back their plundered rights. They cannot get rid of their responsibility by dissolving the Union; they must put down the evil, abolish the wrong. The abolition of slavery, not the dissolution of the Union, is the only way in which they can get rid of the responsibility. "No union with slaveholding" is an excellent sentiment as showing hostility to slavery, but what is union with slavery? Is it living under the same sky, walking on the same earth, riding on the same railway, taking dinner on board of the same steamboat with the slaveholder? No: I can be in all these relations to the slaveholder, but yet heaven-high above him, as wide from him as the poles of the moral universe. "No union with slaveholding" is a much better phrase than that adopted by those who insist that they in America are the only friends of the slave who wish to destroy the Union.

I don't know what it was brought up for. Perhaps it was brought forward to show that I am not infallible, not like his reverence—of Rome. If that was the object, I can relieve the friends of that gentleman entirely, by telling them that I never made any pretensions to infallibility. Although I cannot accuse myself of being remarkably unstable, I cannot pretend that I have never altered my opinion both in respect to men and things. Indeed I have been very much modified both in feeling and opinion within the last fourteen years, and he would be a queer man who could have lived fourteen years without having his opinions and feelings considerably modified by experience in that length of time. When I escaped from slavery, twenty-two years ago [1838], the world was all new to me, and if I had been in a hogshead with the bung in, I could not have been much more ignorant of many things then I was then. I came out running. All I knew was that I had two elbows and a good appetite, and that I was a human being—a sort of nondescript creature, but still struggling for life. The first I met were the Garrisonian abolitionists of Massachusetts. They had their views, opinions, platform, and eloquence, and were earnestly labouring for the abolition of slavery: They were my friends, the friends of my people, and nothing was more natural than that I should receive as gospel all they told me [including 'slavery is constitutional', so the Constitution is a "covenant with death and an agreement with hell"].

—that is, after I went over to Great Britain and came back again—-I undertook the herculean task, without a day's schooling, to edit and publish a paper—to unite myself to the literary profession. I could hardly spell two words correctly; still I thought I could "join" as we say, and when I had to write three or four columns a week,

But I am quite well satisfied, very well satisfied with my [new 'slavery is unconstitutional'] position.

Now, what do I propose? what do you propose? what do we sensible folks propose?—for we are sensible. The slaveholders have ruled the American government for the last fifty years; let the anti-slavery party rule the nation for the next fifty years. And, by the way, that thing is on the verge of being accomplished [in the upcoming Fall 1860 election]. The slave-holders, above all things else, dread the rule of the anti-slavery party that are now coming into power. To dissolve the Union would be to do just what the slaveholders would like to have done [and were already themselves plotting]. Slavery is essentially a dark system; all it wants is to be excluded and shut out from the light. [Cf. John 3:19-20]. If it can only be boxed in where there is not a single breath to fall upon it, nor a single word to assail it, then it can grope in its own congenial darkness, oppressing human hearts and crushing human happiness. But it dreads the influence of truth; it dreads the influence of Congress [and judges who might enforce the Constitution pursuant to the many precedents]. It knows full well that when the moral sentiment of the nation shall demand the abolition of slavery, there is nothing in the constitution of the United States to prevent that abolition. Well, now, what do we want? We want this:—whereas slavery has ruled the land, now must liberty; whereas pro-slavery men have sat in the Supreme Court of the United States, and given the constitution a pro-slavery interpretation against its plain reading, let us by our votes [e.g., for Lincoln] put men [e.g, Salmon P. Chase] into that Supreme Court who will decide, and who will concede [and issue decisions saying], that that constitution is not [pro] slavery.

What do you do when you want reform or change? Do you break up your government? By no means. You say:—"Reform the government;" and that is just what the abolitionists who wish for liberty in the United States propose. They propose that the intelligence, the humanity, the Christian principle, the true manliness which they feel in their hearts,

And that is the way we hope to accomplish the abolition of slavery. Since these questions are put here, it is a bounden duty to listen to arguments of this sort; and I know that the intelligent men and women here will be glad to have this full exposé of the whole question. I thank you very sincerely for the patient attention you have given me. [The End] -19- Later that year (1860), Douglass edited this speech and published it in a slightly revised form as The Constitution of the United States: Is It Pro-slavery or Anti-Slavery (Halifax: T. & W. Birtwhistle, 1860). |

| See Review by the About.com British History Guide |

| See also Douglass' "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?" (Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society, Rochester, New York: 4 July 1852)

"The Anti-Slavery Movement: A Lecture by Frederick Douglass, before the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society, Rochester, 1855" (summary of the four main branches of the anti-slavery movement) “Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation [activism, protests], are those who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its water. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did, and it never will.”—Frederick Douglass, 4 August 1857. As the Courts were enforcing the federal pro-kidnapping law, the "Fugitive Slave Act," Douglass also said: "The only way to make the fugitive slave law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers" [i.e., by rescue operations]. |

| Ed. Note: Frederick Douglass had attended the Radical Abolitionist Convention, 26-28 June 1855, deeming slavery unconstitutional. |

| His Great-Great-Grandson's Site:

Continuing the Activism |

Ed. Note: Examples of

Ed. Note: Examples of