The letter of Patrick Henry to Robert Pleasants (afterwards President of the Virginia Abolition Society), written Jan. 18, 1773, sufficiently shows that his mind had been deeply affected with [persuaded by] the [abolition] movements among the "Friends" [Quakers].

| “Believe me,” says he, “I shall honor the Quakers for their noble efforts to abolish alavery. It is a debt that we owe to the purity of our religion to show that it is at variance with that law that warrants slavery. I exhort you to persevere in so worthy a resolution.” “I believe a time will come when an opportunity will be offered to abolish this lamentable evil.” |

| Ed. Note: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Key (1853), p 36, reprinted more from that letter. |

-70-

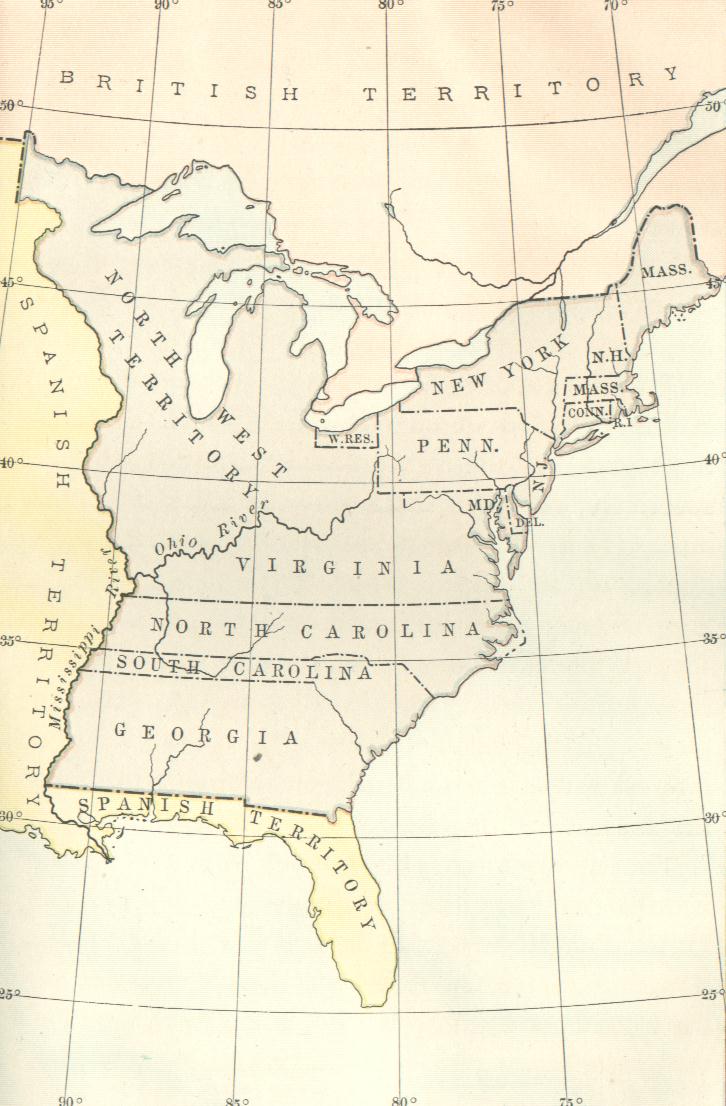

fewest slaves, and where the spirit of opposition to slavery was likewise most efficient and most predominant; while the regions most deeply involved in the sin of slaveholding and least accessible to the principles of emancipation, were precisely the same regions in which the apologists and partisans of British usurpation, were most numerous and influential—the regions in which the spirit of opposition to that usurpation was, to the smallest extent, and with the greatest difficulty roused.

The South was overrun with tories [pro-monarchists], while New England was united in favor of independence, almost to a man. Particular localities at the North might be mentioned, where the prevalence of slaveholding and slave trading was connected with a corresponding sympathy with despotic government.

It may be added, that the names most prominent in the Revolutionary struggle were also among the names most prominent in opposition to slavery, and it is not known that a single advocate of the abolition of slavery was otherwise than a firm asserter of the rights of the Colonies.

That the subsequent decline of the spirit of general liberty,

and the corresponding decline of opposition to slavery, have steadily gone hand in hand, until the propagandists of interminable slavery have derided the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence, and the people of the free States have listened with comparative apathy, are equally undeniable facts.

A full and correct history of the American Revolution, and of the incipient and successive steps taken to unite the Colonies under a new government, cannot fail to identify the movement with opposition to slavery, and the purpose and anticipation of its overthrow. A few documentary facts, in illustration, must suffice here.

The first general Congress of the Colonies assembled in Philadelphia, in September, 1774. Preparatory to that measure, the Convention of Virginia assembled in August of that year, to appoint delegates to the general Congress. An exposition of the rights of British America, by Mr. Jefferson,

-71-

was laid before this Convention, of which the following is an extract:

"THE ABOLITION OF DOMESTIC SLAVERY is the greatest object of desire in these Colonies, where it was unhappily introduced in their infant state. But previous to the enfranchisement of the slaves, it is necessary to exclude further importations from Africa. Yet our repeated attempts to effect this by prohibitions, and by imposing duties which might amount to prohibition, have been hitherto defeated by his Majesty's negative, thus preferring the immediate advantage of a few African corsairs to the lasting interests of the American States, and the rights of human nature, deeply wounded by this infamous practice."—Am. Archives, 4th series, Vol I, p. 696.

The Virginia Convention, before separating, adopted the following resolution:

Resolved, We will neither ourselves import nor purchase any slave or slaves imported by any other person after the first day of November next [1774], either from AFRICA, the WEST INDIES, or ANY OTHER PLACE."—Ib. p 687.

Similar resolutions, had been adopted by primary meetings of the people in county meetings throughout Virginia, during the month of July preceding the State Convention. At the meeting in Fairfax county, [George] WASHINGTON was chairman.

North Carolina also held her Provincial Convention in August, of the same year. Nearly every county in the State was represented. There were sixty-nine delegates. The following resolution was adopted:

"Resolved, That we will not import any slave or slaves, or purchase any slave or slaves imported or brought into the Province by others, from any part of the woild, after the first day of November next."—Ib., p 735.

Similar resolutions had been previously adopted in primary meetings of the citizens m other Southern provinces, now States.

It was after such demonstrations that the first General Congress assembled. Their first and main work was the formation of the "ASSOCIATION" which formed a bond of Union between the Colonies. This was nearly two years before the Declaration of Independence, so that "the Union" of the future States was effected before their Independence, a fact subversive of the common theory of the Constitution, which supposes inde-

-72-

pendent States first, and a compromise of the slave question, in order to the effecting of a Union, afterwards. The following extracts from the articles of Association will show the principles and the terms, so far as the slave question is concerned, upon which this first union was effected:

"We do, for ourselves and the inhabitants of the several Colonies whom we represent, firmly agree and associate under the sacred ties of virtue, honor, and love of our country, as follows:

* * * * * * *

2. "THAT WE WILL NEITHER IMPORT NOR PURCHASE ANY SLAVE imported after the first day of December next, after which time we will wholly discontinue the SLAVE TRADE, and will neither be concerned in it ourselves, nor will we hire our vessels, nor sell our commodities or manufactures, to those who are concerned in it."

* * * * * * *

11. "That a committee be chosen in every county, city, and town, by those who are qualified to vote for Representatives in the Legislature, whose business it shall be attentively to observe the conduct of all persons touching this Association, and when it shall be made to appear, to the satisfaction of a majority of any such committee, that any person within the limits of their appointment has violated this Association, that such majority do forthwith cause the truth of the case to be published in the gazette, to the end that all such FOES to the rights of British America maybe publicly known, and universally contemned as the ENEMIES OF AMERICAN LIBERTY; and thenceforth we respectively will break off all dealings with him or her."

* * * * * * *

14. "And we do further agree and resolve that we will have no trade, commerce, dealings, or intercourse whatever, with any colony or province in North America, which shall not accede to, or which shall hereafter violate this Association, but will hold them as UNWORTHY OF THE RIGHTS OF FREEMEN, and as inimical to the liberties of this country."

* * * * * * *

"The foregoing Association, being determined upon by the Congress, was ordered to be subscribed by the several members thereof, and thereupon, we have hereunto set our respective names, accordingly.

In Congress, Philadelphia, October 20, 1774

PEYTON RANDOLPH,

President,

NEW HAMPSHIRE—John Sullivan, Nathaniel Folsom.

MASSACHUSETTS BAY—Thomas Gushing, Samuel Adams, John Adams, Robert Treat Paine.

RHODE ISLAND—Stephen Hopkins, Samuel Ward.

-73-

CONNECTICUT—Eliphalet Dyer, Roger Sheiman, Silas Deane.

NEW YORK—Isaac Low, John Alsop, John Jay, James Duane, Philip Livingston, Wilham Floyd, Henry Wisner, Simon Bocrum.

NEW JERSEY—James Kinsey, William Livingston, Stephen Crane, Richard Smith, John De Hart.

PENNSYLVANIA—Joseph Galloway, John Dickmson, Charles Humphreys, Thomas Mifflin, Edward Biddle, John Morton, George Ross.

THE LOWER COUNIIES, NEWCASTLE, &c.—Caesar Rodney, Thomas McKean, George Read.

MARYLAND—Matthew Tilghman, Thomas Johnson, jr., William Paca, Samuel Chase.

VIRGINIA—Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, Patrick Henry, jr., Richard Bland, Benjamin Harrison, Edmund Pendleton.

NORTH CAROLINA—William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, Richard Caswell.

SOUTH CAROLINA—Henry Middleton, Thomas Lynch, Christopher Gadsden, John Rutledge, Edward Rutledge—American Archives, 4th Series, p. 915.

Such was the action of the first American Congress. These were items in the “Articles of Association.” How they were received in the Colonies will appear from the following:

| “We, therefore, the Representatives of the extensive District of Darien, in the colony of Georgia, having now assembled in Congress, by authority and free choice of the inhabitants of said District, now freed from their [British] fetters, do resolve:

“5. To show the world that we are not influenced by any contracted or interested [non-impartial] motives, but a general philanthropy for ALL MANKIND, of whatver climate, language, or complexion, we hereby declare our disapprobation and abhorrence of the unnatural practice of slavery in America, (however the uncultivated state of our countt), or other specious arguments may plead for it,) a practice founded in injustice and cruelty, and highly dangerous to our liberties, (as well as lives,) debasing part of our fellow-creatures below men, and corrupting the virtue and morals of the rest, and is laying the basis of that liberty we contend for, (and which we pray the Almighty to continue to the latest posterity,) upon a very wrong foundation. We, therefore, Resolve, at all times to use our utmost endeavors for the manumission of our slaves in this colony, upon the most safe and equitable footing for the master and themselves.”—JAN. 12th, 1775.—Ibid., p. 1136. |

The following action was taken by the Convention of Maryland, held in November, 1774, and re-adopted by a Convention more fully attended, in December:

| “Resolved, That every member of this meeting will, and every person in |

-74-

the province should, strictly and inviolably observe and carry into

execution the Association agreed on by the Continental Congress.” |

The declaration adopted by a general meeting of the freeholders in James City county, in Virginia, in November, 1774, is in these words:

| “The Association entered into by Congress being publicly read, the freeholders and other inhabitants of the county, that they might testify to the world their concurrence and hearty approbation of the measures adopted by that respectable body, very cordially acceded thereto, and did bind and oblige themselves, by the sacred ties of virtue, honor, and love to their country, strictly and inviolably to observe and keep the same in every particular.” |

The proceedings of a town meeting at Danbury, Connecticut, Dec. 12th, 1774, contained the following:

| “It is with singular pleasure we notice the second article of the Association, in which it is agreed to import no more negro slaves, as we cannot but think it a palpable absurdity so loudly to complain of attempts to enslave us while we are actually enslaving others.”—Am. Archives, 4th series, Vol. I., p. 1038.

These are but “specimens [samples] of the formal and solemn declarations of public bodies." “The Articles of Association were adopted by Colonial Conventions, County Meetings, and lesser assemblages throughout the country, and became the law of America—the fundamental Constitution, so to speak, of the first American Union.” “The Union thus constituted was, to be sure, imperfect, partial, incomplete, but it was still a Union, a union of the Colonies and of the people for the great [pro-freedom] objects [purpose] set forth in the articles. And let it be remembered, also, that prominent in the list of measures agreed on in these articles, was the discontinuance of the slave trade, with a view to the ultimate extinction of slavery itself.”* |

That this “sentiment [viewpoint] pervaded the masses of the people,” and that they understood themselves as laying the constitutional foundations of a permanent union and general government by these measures, may be seen by the following extracts from an eloquent paper, entitled “Observations addressed to the people of America,” printed at Philadelphia, in Nov., 1774:

____________________________________

* Speech of Hon. S. P. Chase, of Ohio, U. S. Senate, March 26, 1850. To this speech, and to that of Hon. Lewis D. Campbell, of Ohio, in the House of Representatives of the U. S , Feb. 19, 1850, we are indebted for the quotations made from the American Archives.

-75-

"The least deviation from the resolves of Congress will be treason; such treason as few villains have ever had an opportunity of commuting. It will be treason against the present inhabitants of the colonies—against the millions of unborn generations who are to exist hereafter in America—against the only liberty and happiness which remain to mankind—against the last hopes of the wretched in every corner of the world; in a word, it will be treason against God. * * * WE ARE NOW LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS OF AN AMERICAN CONSTITUTION.

"Let us, therefore, hold up everything we do to the eye of posterity. They will most probably measure their liberties and happiness by the most careless of our footsteps. Let no unhallowed hand touch the precious seed of liberty. Let us form the glorious tree in such a manner, and impregnate it with such principles of life, that it shall last forever. * * * I almost wish to live to hear the triumphs of the jubilee in the year 1874; to see the models, pictures, fragments of writings, that shall be displayed to revive the memory of the proceedings of the Congress of 1774. If any adventitious circumstance shall give precedency on that day, it shall be to inherit the blood, or even to possess the name, of a member of that glorious assembly."—Amer. Arch., 4 ser., vol. i, p. 976.

The spirit of 1774 was not extinct or languishing in 1776, a year memorable not only for the Declaration of American Independence, but for the previous enunciation of the same self-evident truths, applied to the sin of slavery, in a more elaborate and thorough elucidation of the whole subject than had before appeared.*

The argument of Dr. Hopkins against slavery is introduced by a notice of the action of Congress against the slave trade, and the statement that the traffic "has now but few advocates, and is generally exploded and condemned." The treatise contains the remarkable statement that "the slavery that now takes place," (in distinction from that of ancient times,) is "without the express sanction of civil government."†

| Ed. Note: This same point of view was expressed by

Gerrit Smith, Letter of Gerrit Smith to Hon. Henry Clay (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1839), p 19

George Mellen, Unconstitutionality of Slavery (Boston: Saxton & Pierce, 1841), pp 431-432

Lysander Spooner, Unconstitutionality of Slavery (Boston: Bela Marsh, 1845), p 23

Abraham Lincoln, Peoria Speech (1854),

p 221

Lewis Tappan, et al., Proceedings of Convention (New York, 26-28 June 1855), p 34. |

This idea will now appear strange to most per-

____________

*"A Dialogue concerning the Slavery of the Africans, showing it to be the duty and interest of the American States to emancipate all their African Slaves. Dedicated to the Honorable the Continental Congress." By Samuel Hopkins, D.D., of Newport, R. I.

†The same idea seems involved in another portion of the treatise. "The several legislatures in these colonies," says the writer, "the magistrates and the body of the people, have doubtless been greatly guilty in approving and encouraging, or at least conniving at, this practice" (i.e., slaveholding). This is certainly remarkable language, especially from so accurate and discrimin-

-76-

sons. But the careful and reflecting reader of the history we have given in the preceding chapters, will have been led to inquire when and how the "express sanction," of "civil government" had been given to slavery in any form that could entitle it to the reputation of being legalized. The decision of Lord Mansfield in the Somerset case, four years previous, may have been in the mind of Hopkins, and he is known to have been in correspondence with Granville Sharp, with whose views the reader is acquainted.

What seems most remarkable is, that a treatise containing such a statement should not only have been extensively circulated without being questioned, but republished, and still more extensively circulated, nine years afterwards, by anti-slavery societies under the auspices of such statesmen as Franklin and Jay. If it be conceded that American slavery was "without the express sanction of civil government," that it was not, in a strict and proper sense, legalized, at the time when Hopkins wrote his treatise, a few months before the Declaration of Independence, it would be a curious question how it could have become legalized since. Assuredly, the far-famed Declaration of inalienable human rights cannot have given it any new validity!

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." "To secure these rights, governments are instituted among men." "We, therefore, the representatives of the United States of America," &c. &c.

We enter into no argument here concerning the legal effect of that immortal Declaration, upon the tenure of slave property. But it is important to note down distinctly the historical facts. It was the "unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United (not disunited) States of America." The "Union" had already been formed, and has never since been dissolved.

____________

ative a writer as Hopkins, if slavery were universally and unhesitatingly held to be legal. Legislatures and magistrates are not commonly spoken of as "conniving" (closing their eyes upon) practices which are admitted to be legal! Such language describes their culpable neglect to suppress and punish practices that are unlawful.

-77-

On this point, there can be no mistake.* It was not only a Declaration of the States by their delegates, but was separately ratified by all the States, afterwards, and has never been repudiated or repealed since. In connection with the previous Articles of Association, it was the only constitution of the United States, until the adoption of the "Articles of Confederation" in 1778; and with these, thenceforward, until the adoption of the present Federal Constitution, in 1789.

It had power to legalize Acts of Congress and Treaties, as also to absolve citizens from their allegiance to the king of Great Britain.† Its repeal would have been an abandonment of Independence, and a return to the condition of colonies.

Besides this, the original thirteen States, except Connecticut and Rhode Island, formed Constitutions bearing date, variously, from 1776 to 1783. "They generally recognized, in some form or other, the natural rights of men, as one of the fundamental principles of the government. Several of them asserted these rights in the most emphatic and authoritative manner." So that the fundamental principles and self-evident truths of the Declaration of 1776 became the constitutional law of the several States. Vide Spooner, p. 46.

The Articles of Confederation, formed in 1778, contained no recognition of slavery, nor of distinctions of color. It was never pretended that, under these articles, the slaveholder whose slaves had escaped to another State, had any legal power to force him back.

In 1779 the Continental Congress ordered a pamphlet to be published, entitled, "Observations on the American Revolution," of which the following is an extract:

"The great principle (of government) is and ever will remain in force,

____________

*The reader is referred to the unanswered and unanswerable argument of John Quincy Adams on this point, in his address at Newburyport, 4th of July, 1837.

†John Hancock, President of Congress, in a letter to the Convention of New Jersey, then in session, and inclosing a copy of the Declaration of Independence, speaks of it as being "the ground and foundation of a future government." If the "ground and foundation" be removed, what becomes of the superstructure? But if this "ground and foundation" remains, what becomes of the validity of slave laws?

-78-

that men are, by nature, free; as accountable to Him that made them, they must be so; and so long as we have any idea of divine justice, we must associate that of human freedom. Whether men can part with their liberty is among the questions which have exercised the ablest writers; but it is conceded, on all hands, that the right to be free CAN NEVER BE ALIENATED; still less is it practicable for one generation to mortgage the privileges of another."

A more forcible denial of the possibility of legalizing slavery could not easily have been penned.

About this time, or not long after, Mr. Jefferson wrote his celebrated Notes on Virginia, in which his testimonies against slavery are so various and emphatic, that we hesitate what paragraph to select for quotation. The following serves to show what such men, at that time, expected and desired to see accomplished, and what was then, in Mr. Jefferson's opinion, the state of sentiment in the Southern States.

| "I think a change is already perceptible since the [1776] origin of the present revolution. The spirit of the master is abating, that of the slave is rising from the dust, his condition mollifying, THE WAY, I HOPE, PREPARING, UNDER THE AUSPICES OF HEAVEN, FOR A TOTAL EMANCIPATION." |

| Ed. Note: Full Citation: Thomas Jefferson [1743-1826], Notes on the State of Virginia (Philadelphia: Prichard and Hall, 1788) [Excerpt]. |

General [Horatio] Gates [1728-1806], the conqueror of [British General John] Burgoyne [1722-1792], emancipated, in 1780, his numerous slaves.

From the beginning to the close of the war, one uniform language was held. Soon after the peace of 1783, Congress issued an address to the States, drawn up by Mr. Madison, a main object of which was to ask the provision of funds to discharge the public engagements. The plea is thus urged:

"Let it be remembered, finally, that it has ever been the pride and boast of America that the rights for which she contended were the rights of human nature. By the blessing of the Author of these rights on the means exerted for their defence, they have prevailed against all opposition, and form the basis of THIRTEEN INDEPENDENT STATES."

The expression of similar sentiments did not then cease, nor were they confined to public acts.

"Jefferson, Pendleton, Mason, Wythc, and Lee, while acting as a committee of the House of Delegates of Virginia, to revise the State Laws, prepared a plan for the gradual emancipation of the slaves, by law."

In addition to these, "Grayson, St. George Tucker, Madison, Blair, Page, Parker, Edmund Randolph, Iredell, Spaight, Ramsey, McHenry, Samuel

-79-

Chase, and nearly all the illustrious names south of the Potomac, proclaimed it before the sun, that the days of slavery were beginning to be numbered."—Power of Congress over the "District of Columbia," by T. D. WELD [1838].

But it is needless to multiply these references. So universal were these sentiments, that Mr. Leigh, in the Convention of Virginia, in 1832, took occasion to say:

"I thought, till very lately, that it was known to every body that, during the Revolution, and for many years after, the abolition of slavery was a favorite topic with many of our ablest statesmen, who entertained with respect all the schemes which wisdom or ingenuity could surest for its accomplishment "

Mr. Faulkner, in the same Convention, alluded to the same fact, as did also Gov. Barbour, of Virginia, in the United States' Senate, in 1820.

These professions of the fathers of our republic were not totally unaccompanied with corresponding action.

The articles of Association, including the solemn pledge to discontinue the slave trade, appear to have been generally respected and observed. That there were unprincipled men who evaded or transgressed them, as there were other traitors to the cause of liberty, there can be no doubt After the close of the war, this is known to have been the fact But the States took early measures for its suppression.

"The first opportunity was taken, after the Declaration of Independence, to extinguish the detestable commerce so long forced upon the province (Virginia) In October, 1778, during the tumult and anxiety of the Revolution, the General Assembly passed a law, prohibiting, under heavy penalties, the further importation of slaves, and declaring that every slave imported thereafter, should be immediately set free " "The example of Virginia was followed, at different times, before the date of the Federal Constitution, by most of the other States."—Walsh's "Appeal"—Vide "Friend of Man," June 21, 1837 Copied from "Human Rights."

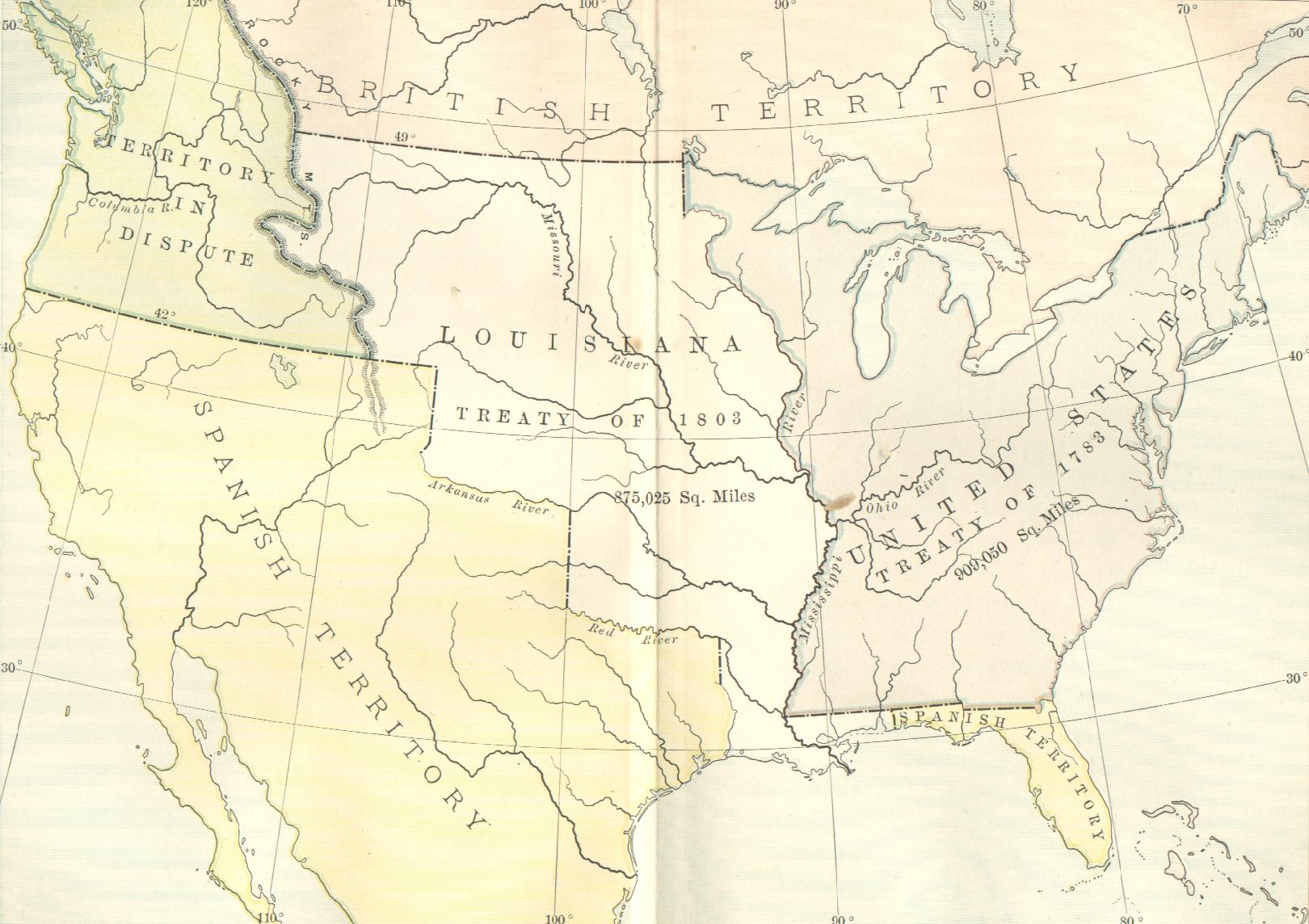

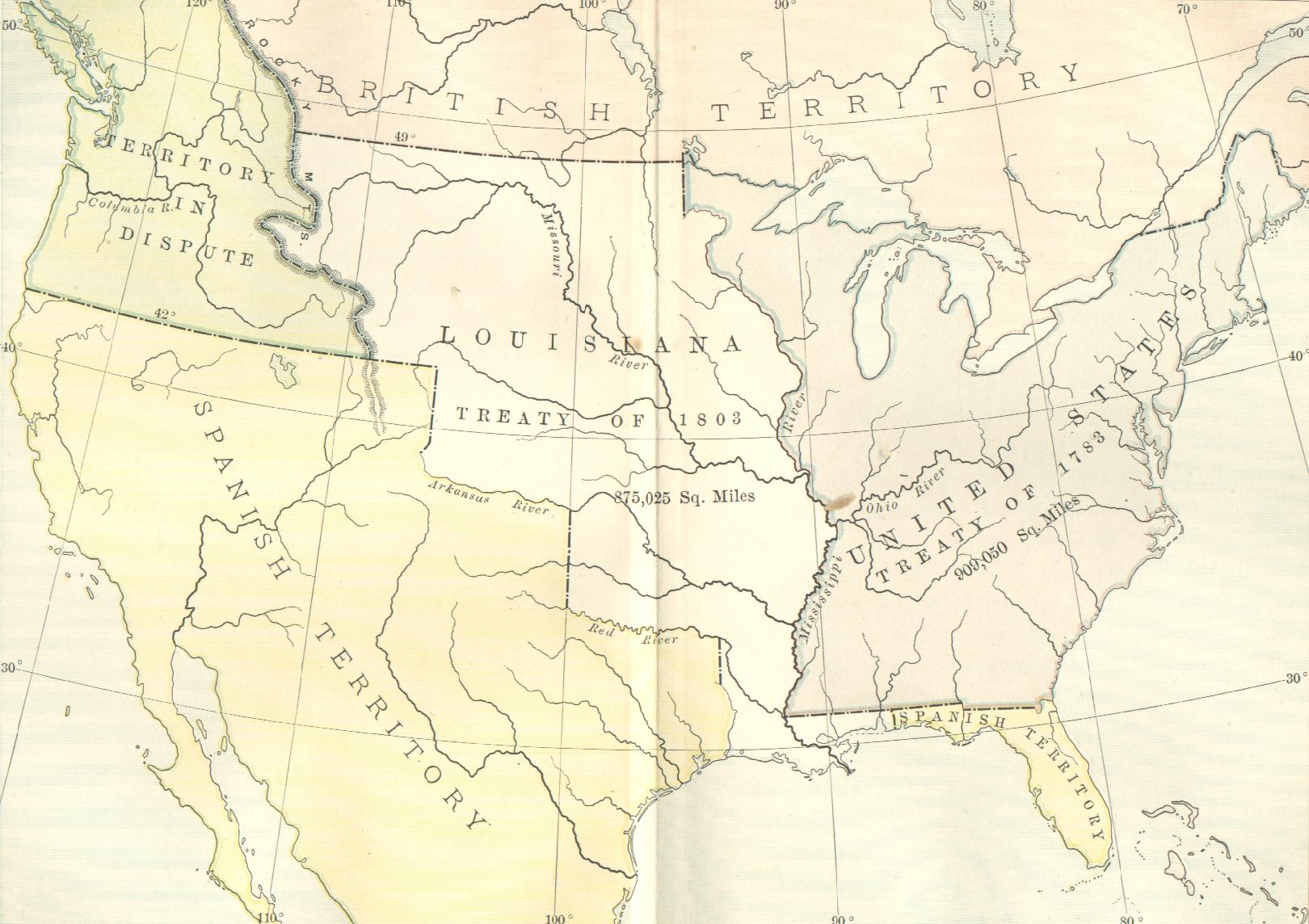

"We are not aware that any State allowed the importation of slaves at the time," when the Constitution was adopted "The first State that renewed the traffic, so far as we know, was S. Carolina." in 1803 —"Human Rights"—"F of Man;" as above.

Under what influences, and with what activity, the slave trade was resumed, from 1803 to 1808, will be shown in the proper place.

-80-

CHAPTER IX.

ERA OF FORMING THE FEDERAL CONSTITUTION.

Prevailing Sentiment—Washington—Luther Martyn—Wilhim Pinckney—Northwestern

Territory—Ordinance of 1787—Madison—"Understandings"—Wilson—

Heath—Johnson— Randolph—Patrick Henry—Iredell—"The Federalist," by Jay,

Madison, and Hamilton—Ratifications—Rhode Island—New York—Virginia—

North Carolina—Amendment—"Due process of law."

FROM the close of the Revolutionary war in 1783, to the sitting of the Constitutional Convention, was a space of only four years. Thence, two more years bring us to the adoption, of the Constitution, in 1789. What was the prevailing sentiment of that period?

In a letter to Robert Morris, dated Mount Vernon, April 12, 1786, George Washington said

"I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it, (slavery,) but there is only one proper and effectual mode in which it can be accomplished, and that is by legislative authority, and this, so far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting "—9 Sparks's Washington, 158.

In a letter to John F. Mercer, September 9, 1786, he reiterated this sentiment:

"I never mean, unless some particular circumstances should compel me to it, to possess another slave by purchase, it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted, by which slavery in this country may be abolished by law."—Ibid.

And in a letter to Sir John Sinclair, he further said:

"There are in Pennsylvania laws for the gradual abolition of slavery, which neither Virginia nor Maryland have at present, but which nothing is more certain than they must have, and at a period not remote."

By his last will and testament he made all his slaves free.

-81-

The testimonies of Franklin, Rush, and Jay, in strong opposition to slavery, have been cited in another connection.*

We have now traced the history of the "peculiar institution" down to the time when the Federal Constitution was about to be formed. Exceedingly "peculiar" indeed, are the vouchers for its authenticity and legality down to that point in our national history. What occurred while the Federal Constitution was in process of forming, is the next historical fact to be inquired after. What was likely to have occurred, and even, indeed, what could have occurred, may well nigh be read in the mere light of the historical facts already noticed. Those facts, at least, should not be left out of the account, in any attempts at a historical exposition of the Constitution, if, indeed, the advocates of the "institution" adventure into the field of history at all, in defence of their claims.

The simple history, and not the argument, must occupy, at present, our attention, and yet it is in the light of the pending controversy that we should ponder the facts. It is that contest that gives them their value, and they should be collected, arranged and studied with a view to the points to be illustrated and determined by them.

Luther Martin, of Maryland, advocated the abolition of slavery, in the Federal Convention of 1787, and in his Report of the proceedings of that Convention to the Legislature of bis own State.

William Pinckney, of Maryland, in the House of Delegates in that State, in 1789, urged, strongly, the abolition of slavery. We will give but a specimen of his language on that occasion.

| "Sir—Iniquitous and most dishonorable to Maryland, is that dreary system of partial bondage which her laws have hitherto supported with a solicitude worthy of a better object, and her citizens by their practice, countenanced. Founded in a disgraceful traffic, to which the parent country lent its fostering aid, from motives of interest, but which even she would have disdained to encourage, had England been the destined mart of such inhuman merchandize; its continuance is as shameful as its origin.'' |

____________

*Chapter IV.

-82-

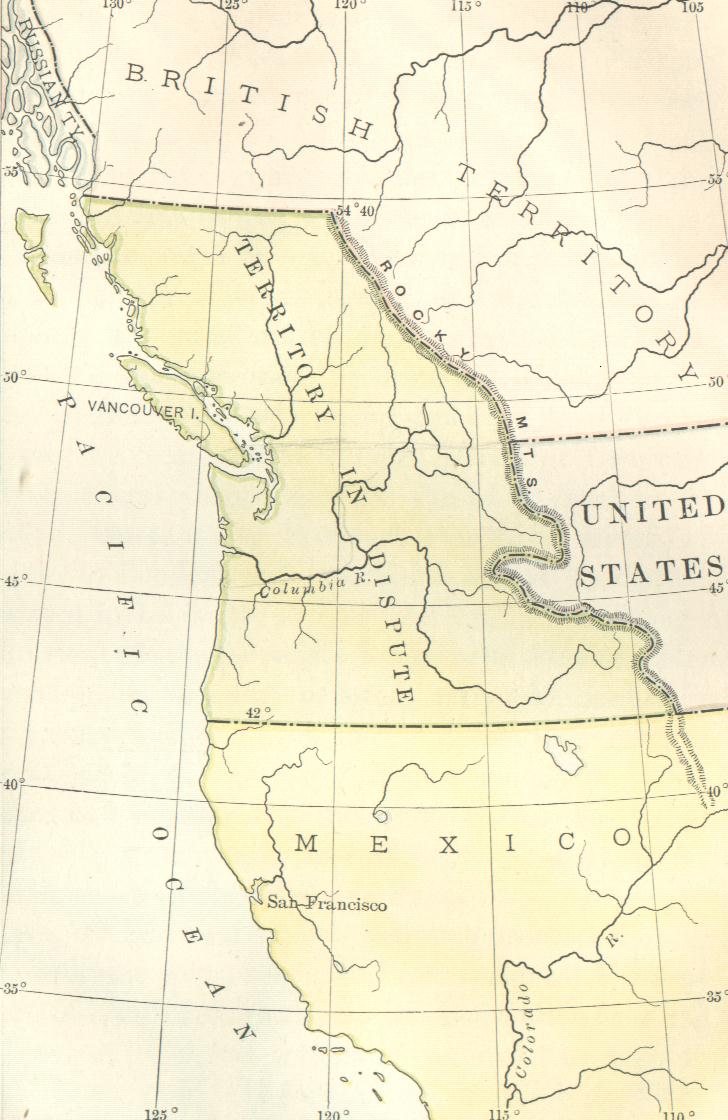

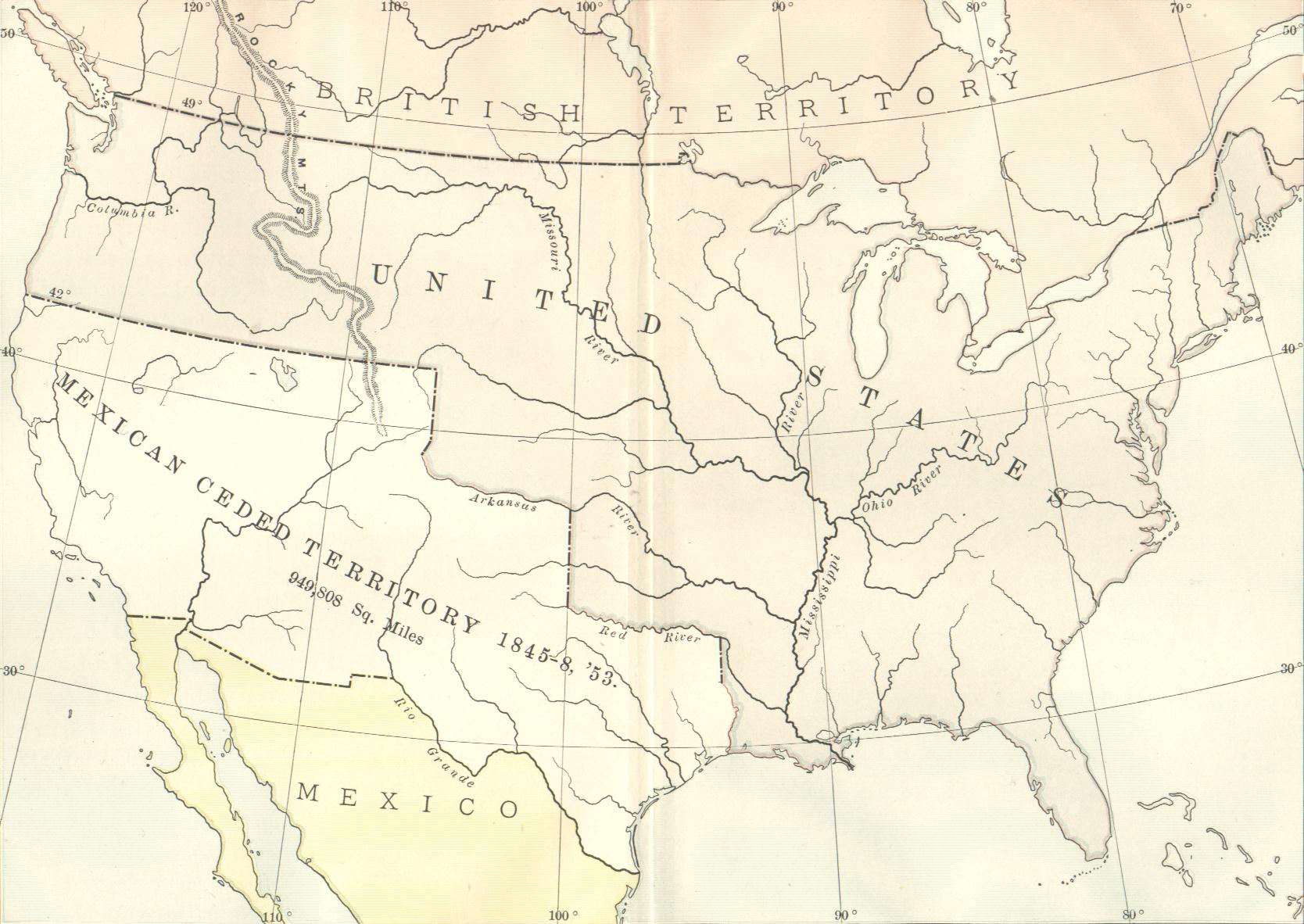

NORTHWESTERN TERRITORY—ORDINANCE OF 1787.

While the Convention for drafting the Constitution of the United States was in session, in 1787, the Old Congress passed an ordinance abolishing slavery in the North-Western Territory, and precluding its future introduction there. The first Congress under the new Constitution ratified this ordinance, by a special act. It received the approval of Washington, who was then fresh from the discussions of the Convention for drafting the Federal Constitution. The measure originated with Jefferson, and its ratification in the new Congress received the vote of every member except Mr. Yates, of New York, the entire Southern delegation voting for its adoption. By this ordinance slavery was excluded from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa.

The series of articles is preceded by this preamble:

| "And for extending the fundamental principles of civil and religious liberty, which form the basis whereon these republics, their laws and constitutions, are erected; to fix and establish those principles as the basis of all laws, constitutions, and governments, which forever hereafter shall be formed in said Territory; to provide also for the establishment of States, and permanent government therein, and for their admission to a share in the Fedcrul Councils at as early a period as may be consistent with the general interest:—Be it ordained and established," &c. &c. |

Then follow the articles. The sixth is as follows:

| "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted; provided, always, that any person escaping into the same, from whom labor or service may be lawfully claimed, in any one of the original States, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed, and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or service, as aforesaid." |

"The Constitution," it is claimed, "guaranties slavery." And "the compromises of the Constitution" are very generally conceded, even among those who disrelish and controvert the claim. We enter not now into matters of mere opinion. But the continuity and fidelity of the history we have attempted, compel us to attend to the facts.

-83-

Whatever those facts are, they are such as are interlinked, indissolubly, with the historical facts of the last previous chapter, and the preceding ones. History must be understood, if at all, in its connections.

The Constitution is in the hands of the people. We need not copy here its provisions. No claimant of the Constitutional guaranties of slavery adventures to rest the claim on the mere words of that instrument. He well knows that neither the terms "slave" nor "slavery" are to be found there. He goes out of the instrument for its exposition, and reposes on supposed facts, in the shape of "understandings" then entertained.

What were the "understandings" of that period? In the preceding chapter may be seen some of them. It is in place here to record more. We have seen what they were, up to the time of the framing and adopting of the Federal Constitution. What were they, then?

In the Convention that drafted the Constitution—

| Mr. Madison declared, he "thought it wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men."—3 Mad Pap., 1429.*

"On motion of Mr. Randolph, the word 'SERVITUDE' was struck out, and 'SERVICE' unanimously inserted—the former being thought to express the condition of SLAVES, and the latter the obligation of FREE PERSONS."—Ib. 3, p. 1569. |

Such were the "understandings" of the Convention that drafted the Constitution. And with what "understanding" was it adopted by the people, in their State Conventions? Let us see.

____________

*In other words, Mr. Madison would not consent that the Constitution should recognize even the legality of slavery! This was a still more full, confident, and emphatic expression of the idea we have before quoted from Dr. Hopkins.

-84-

| vania. * * * The new States which are to be formed will be under the control of Congress in this particular, and slavery will never be introduced among them."—2 Elliot's Debates, 452. |

In another place, speaking of this clause, he said:

| "It presents us with the pleasing prospect that the rights of mankind will be acknowledged and established throughout the Union. If there was no other feature in the Constitution but this one, it would diffuse a beauty over its whole countenance. Yet the labor of a few years, and Congress will have power to exterminate slavery from within our borders."—Ib. 2, p. 484. |

In the Ratification Convention of Massachusetts, Gen. Heath said:

| "The migration or importation, &c., is confined to the States now existing only, new States cannot claim it. Congress by their ordinance for creating new States some time since, declared, that the new States shall be republican, and that there shall be no slavery in them."—Ib. 2, p. 115. |

Nor were these views and anticipations confined to the free States. In the Ratification Convention of Virginia, Mr. Johnson said:

| "They tell us that they see a progressive danger of bringing about emancipation. The principle has begun since the Revolution. Let us do what we will, it will come round. Slavery has been the foundation of much of that impiety and dissipation which have been so much disseminated among our countrymen. If it were totally abolished, it would do much good."—Ib |

Gov. Randolph rebuked those who expressed apprehensions that its influence might be exerted on the side of freedom, by saying:

| "I hope that there are none here who, considering the subject in the calm light of philosophy, will advance an objection dishonorable to Virginia, that, at the moment they are securing the rights of their citizens, there is a spark of hope that those unfortunate men now held in BONDAGE may, by the operation of the General Government, be made FREE."—Ib. 3, p. 598. |

Patrick Henry, in the same Convention, argued "the power of Congress, under the United States' Constitution, to abolish slavery in the States," and added :

| "Another thing will contribute to bring this event about. Slavery is detested We feel its effects. We deplore it with all the pity of humanity."—Debates Va. Convention, p. 463. |

"In the debates of the North Carolina Convention, Mr. Iredell, afterwards a Judge of the United States Supreme Court, said—

| 'When the entire abolition of slavery takes place, it will be an event which must be pleasing to every generous mind, and every friend of human nature.'"—"Power of Congress," &c., pp 31-2. |

-85-

Such are a few specimens of the expressed "understandings" with which the people adopted the Constitution.

Another class of historical facts; of the utmost importance to a right understanding of the slave question in America, relates to the expositions and arguments addressed to the people of the United States to persuade them to adopt the Federal Constitution. It is well known that the people were sensitively jealous of their rights at that period, and fearful of the encroachments of despotic power. A strong party, of which Mr. Jefferson (a prominent and zealous propagandist of abolitionism) was understood to be the nucleus, and afterwards became the successful presidential candidate, opposed the adoption of the Federal Constitution, as prepared by the Convention, on the ground of its alleged defects in not providing sufficient securities for personal rights, and a more ample and explicit enunciation of the self-evident truths of the Declaration of 1776.

This opposition [claiming that the proposed Constitution was not sufficiently pro-freedom] drew out the distinguished statesmen, Madison, Jay, and Hamilton, in a joint and elaborate defence of the Constitution as drafted, comprising a series of papers known as "The Federalist," and since collected into a large volume. These papers were extensively circulated before the action of the States, and were largely instrumental in securing their desired object.—No. 39 of "The Federalist," by James Madison, contains the following:

| "The first question that offers itself is, whether the general form and aspect of the government be strictly republican. It is evident that no other form would be reconcilable with the genius of the people of America, and with the fundamental principles of the Revolution, or with that honorable determination which animates every votary of freedom, to rest all our political experiments on the capacity of MANKIND for SELF-GOVERNMENT. If the plan of the Convention, therefore, be found to depart from the republican character, its advocates must abandon it, as no longer defensible." |

Mr. Madison proceeds, at some length, to discuss the question, "What are the distinctive characters of the republican form"? After distinctly repudiating the aristocracies and oligarchies of Holland, Venice, Poland, and England, as not being republican, though sometimes "dignified," very impro-

-86-

perly, "with the appellation," Mr. Madison proceeds further to define a republican government as one whose officers are appointed by THE PEOPLE, &c.

| "It is essential to such a government," says he, "that it be derived from the great body of society, NOT from an inconsiderable portion, OR, a favored class of it." |

And this is the same Mr. Madison, who, in the Convention for drafting the Constitution which he was now recommending, had insisted that the instrument must not recognize the legality of slavery.

The adoption of the Federal Constitution was thus successfully urged upon the people, by representing it as laying the foundation of the Government upon "the principles of the Revolution"—the principles of '76,—the principles promulgated so effectively by Mr. Jefferson, who had said—

| "The true foundation of republican government is the EQUAL RIGHTS OF EVERY CITIZEN, in his PERSON and PROPERTY, and in their MANAGEMENT," and who had explicitly designated the slaves as "citizens."* |

In No. 84 of "The Federalist" several pages are devoted to a consideration of what was evidently understood to be a vital point, in the minds of the people, who were so soon to decide on the adoption or rejection of the proposed Constitution.

"The most considerable of the remaining objections," says the writer, "is, that the plan of the Convention contains no bill of rights.'

The writer speaks of "the intemperate partisans of a bill of rights," and of their "zeal in this matter." This shows that many of the people were sensitive on this point, and that the friends of the proposed Constitution were afraid of its being rejected in consequence.

And how did "The Federalist" successfully allay this jealousy, and persuade the people to adopt the proposed Constitution?

____________

*With what execration should the statesman be loaded, who, permitting one half of the citizens thus to trample upon the rights of the other, transforms those into despotsm, destroys the morals of the one part, and, the amor patriæ of the other."—Notes on Virginia.

-87-

It was done, first, by citing a number of specific provisions in the Constitution, equivalent, (as was claimed) to so many corresponding items in a bill of rights; and, second, by citing the PREAMBLE to the Constitution, setting forth its objects "to secure the blessings of liberty," &c. to "the people of the United States." This Preamble, as being a part of the Constitution, and its very basis, to which all the rest was conformed, was represented as being not only a bill of rights in the general, but "a better recognition of popular rights " than could otherwise have been framed, and less liable to be set aside, under a "plausible pretence," by men "disposed to usurp power."*

The objectors had desired such a bill of rights as several of the States, particularly Massachusetts, had already adopted, and under which, before that time, the Courts of Massachusetts had decided slavery to be illegal. Yet "The Federalist" assured them that the Constitution was more than the equivalent of such bills of rights.

It was under the pressure of expositions and arguments like these, from leading members of the Convention, that the people were persuaded to ratify the Constitution that had been elaborated with closed doors. They ratified it with "the understanding," so frequently expressed by and among them, that the Constitution was in favor of freedom. We know of no record in which the ratification of that instrument was urged, either at the North or at the South, on the ground that it was the guaranty of any form of despotism—or on the ground that the conflicting interests of liberty and slavery had been compromised. The whole current of the political literature of that period forbids the idea that any such appeals could have been adventured.

But the people, though they ratified the Constitution, were

____________

*The reader is doubtless familiar with the modern [pro-slavery] pleas, that the Preamble has no controlling power over the Constitution; that it does not furnish a criterion for Constitutional exposition; and that, in fact, it is no part of the Constitution! We may judge what would have been the fate of the proposed Constitution, if its friends had outstript its enemies in representing it thus!

-88-

not satisfied to do so without insisting upon important [bill-of-rights-type] amendments. The Conventions of Virginia, North Carolina and Rhode Island, proposed a provision as follows:

| "No FREEMAN ought to be taken, imprisoned, or disseized of his freehold, liberties, privileges, or franchises, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any manner despoiled or deprived of his life, liberty, or property, BUT BY THE LAW OF THE LAND."—Elliot's Debates, 658. |

New York proposed a different provision:

| "No PERSON ought to be taken, imprisoned, or disseized of his freehold, or be exiled, or deprived of his privileges, franchises, life, liberty, or property, but by due process of law."—1 Ibid, 328. |

These various propositions came before Congress, and that body, at its first session, agreed upon several amendments to the Constitution, which were subsequently ratified by the States. That which related to personal liberty was expressed in these comprehensive words:

| "No person * * * * shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law."—Cons., Amend., Art. 5. |

It is to be noted, as an important historical fact, that this remarkable provision is an amendment coming in after the original instrument had been ratified, thus over-riding and controlling, like all other amendments, whatever in the original instrument may have been supposed to be of a contrary bearing.

The ratification of Rhode Island was longest withheld, and was most remarkable in its mode of expression. It was, in fact, conditional. It specified a long list of declarations of rights, and then said:

| "Under these impressions, and declaring that the rights aforesaid cannot be abridged, and that the explanations aforesaid are consistent with the said Constitution, and in confidence that the amendments hereafter mentioned will receive an early and mature deliberation, and conformably to the 5th article of said Constitution, speedily become parts thereof: We the said delegates," &c., &c., "do assent to and ratify the said Constitution." |

Among these declarations of rights were some equivalent to those of the Declaration of Independence.

Among the proposed amendments, above mentioned, was the following

| "As a traffic tending to establish or continue the slavery of any part of the human species, is disgraceful to the cause of religion and humanity, that |

-89-

| Congress as soon as may be, promote and establish such laws as may effectually prevent the importation of slaves, of any description, into the United States." |

From this it is seen, that the State whose citizens were most deeply engaged in the lucrative importation of slaves, the only State, perhaps, that was growing rich by the continuance of the slave system consented to ratify the Federal Constitution only on condition that the traffic should be speedily prohibited. No other ratification of the Constitution was ever made by Rhode Island. She never consented to the twenty years' delay of that prohibition.

-90-

CHAPTER X.

OF DIRECT ANTI-SLAVERY EFFORTS, INCLUDING ECCLESIASTICAL

ACTION, FROM THE PERIOD OF THE REVOLUTION TO

THE CLOSE OF THE LAST CENTURY, AND THE ABOLITION

OF SLAVERY IN THE NORTHERN STATES.

Republication of Hopkins' Dialogue (1785)—Edwards' Sermon (1791)—Anti-Slavery

Meeting at Woodbridge, N. J. (1783)—Abolition Societies in Pennsylvania, New

York, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Maryland, Virginia, New Jersey, Delaware—

Names of distinguished abolitionists—Memorial to Leg. of New York, by Jay,

Hamilton, &c.—Petitions to Congress, by B. Franklin and others—Discussions in

Congress—William and Mary College (Va.)—Action of Methodist E. Conference—

Presb. General Assembly—Baptists—Action of the States—Virginia, Delaware,

Rhode Island, Vermont—Massachusetts—Pennsylvania—New Hampshire,

Connecticut—New York—New Jersey—Census of remaining slaves.

SIGNIFICANT as are the facts recorded in the two preceding chapters, they would fail of producing their full and proper impression, unless connected with an account of other movements witnessed at the same time, and extending to a still later period of our history. It was not in the National Councils alone, the resolutions and acts of Congress, the corresponding proceedings of State and County Conventions, the action of State legislatures, and the declarations of prominent statesmen, that the rising of sentiment against slavery was apparent. Then, as at other times, under popular institutions, such manifestations were to be regarded as evidences of a still broader and deeper current of public opinion, that was producing them. Then, as now; here, as in Great Britain, the public bodies and functionaries nearest to the people, freshest from their bosom, most accessible to their inspection,

-91-

and most directly and vitally amenable to them ("Representatives" and "Commons," in distinction from "Lords" and "Senates"), were most deeply imbued with the principles of justice and freedom—a general fact of incalculable weight in the argument for thoroughly democratic institutions.

And back of this general public sentiment against slavery, were the moral influences that had been operating in that direction—the religious testimonies and the ecclesiastical action before mentioned. The power of the press, and of voluntary association, irrespective of sect, followed soon afterward.

The first edition of [Rev. Dr. Samuel] Hopkins' Dialogue was published at Norwich, Connecticut, early in 1776, as before stated.

| Ed. Note: Full Citation: Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803), A Dialogue Concerning the Slavery of the Africans: Shewing it to be the Duty and Interest of the American Colonies to Emancipate All Their African Slaves. With an Address to the Owners of Such Slaves. Dedicated to the Honourable the Continental Congress. To Which is Prefixed, the Institution of the Society, in New York, For Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and Protecting Such of Them as Have Been, or May Be, Liberated (Norwich: J.P. Spooner, 1776). |

Its circulation was extensive, and is known to have produced a powerful impression upon the minds of reflecting men, including some in high stations. A second edition was issued in New York in 1785, "by vote of the society for promoting the manumission of slaves "—of which John Jay [later Chief Justice 1789-1794] was President, and which had been formed January 25th of that same year.

| Ed. Note: Full Citation: Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803) A Dialogue Concerning the Slavery of the Africans: Shewing it to be the Duty and Interest of the American States to Emancipate All Their African Slaves (New York: R. Hodge, 1785). |

Another publication, of great weight and influence, was the celebrated sermon of Dr. Jonathan Edwards, of New Haven, Conn., afterwards President of Union College, Schenectady; preached before the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom, &c., Sept. 15, 1791. It is a masterpiece of logical argument, and was extensively circulated by the manumission and abolition societies of that period, as it has been since by the more modern anti-slavery societies.

| Ed. Note: Full Citation: Jonathan Edwards (1745-1801), The Injustice and Impolicy of the Slave Trade, and of the Slavery of the Africans: Illustrated in a Sermon Preached Before the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Freedom, and for the Relief of Persons Unlawfully Holden in Bondage, at Their Annual Meeting in New Haven, September 15, 1791 (New Haven: T. and S. Green, 1791). See excerpt cited at p 111, infra. |

By these two publications, the argument against slavery was placed upon a deeper and broader theological and metaphysical basis, and was pushed to more startling and radical conclusions, than in any previous writings on the subject with which we are acquainted. And it may safely be said that no later writers have gone beyond them in affirming the inherent sinfulness and deep criminality of slaveholding, and the duty of immediate and unconditional emancipation. Particularly is this true of the sermon of Edwards. If others have insisted upon these points with more vehemence of declamation, or

-92-

with a more brilliant display of rhetoric, there is no one who has more deliberately and triumphantly demonstrated those truths by a process of cool iron-linked argument, placing it forever beyond the power of man to unsettle them, without dethroning the moral sense, rejecting the inductions of reason, and abjuring the Christian religion. It is not known that any writer or public speaker of any note, has ever attempted to grapple with that sermon, attempting to criticize, or to confute it.

And yet this forbearance cannot be because the language employed is more smooth and mild than that of other writings that have been criticized as denunciatory. The preacher distinctly charges upon the slaveholder the crime of man-stealing, and the repetition of the crime every day he continues to hold a slave in bondage. He charges him also with "theft or robbery"—nay, with "a greater crime than fornication, theft, or robbery." He predicts that, "if we may judge the future by the past, within fifty years from this time it will be as shameful for a man to hold a negro slave, as to be guilty of common robbery or theft." In an appendix, Dr. Edwards answers objections against immediate emancipation, just as modern abolitionists answer them now.

Such were the sentiments which the abolition societies of the last century, directed by the patriots of the American Revolution, the founders of the Union, the framers and the adopters of the Federal Constitution, were intent to circulate through the country. If some of them, as statesmen, did not fully carry out the idea of immediate emancipation taught in such writings, they circulated them among the people, nevertheless. These were the effective weapons of their warfare against slavery, so far as they succeeded at all.

By these doctrines, mainly, the public conscience was reached, and the measures put in progress, which finally resulted in the abolition of slavery in some of the States. The doctrines are none the less true and trustworthy because the partial adoption of them produced but partial and tardy results. If the abolition of slavery in some of the States was so slow and gradual as to occupy a whole generation or more in the process, if in

-93-

some others it still lingers, or has been indefinitely postponed, while the system has strengthened itself, and the slave power has assumed the control of the nation and stealthily reversed its policy, the fault does not lie in the teachings of Hopkins and Edwards, but in the mistaken prudence of those who thought it more wise and safe to follow but partially in practice what was admitted to be right and true in the abstract. To this single fallacy, the failure of the Bevolutionary abolitionists, in their intended overthrow of American slavery, may be distinctly traced.

“The ruse of gradualism,” identical with deferred repentance for sin, produced its accustomed and legitimate fruits. It deceived them, as it deceives the greater portion of mankind.

We may honor their earnest endeavors, nevertheless, and rejoice in the success, however limited, with which their labors were crowned. It should be ours to emulate their love of freedom, and avoid their mistakes, the repetition of which would be less excusable in us.

An important and highiy spirited anti-slavery meeting is said to have been held at Woodbridge, New Jersey, appropriately convened on the 4th of July, 1783, just seven years after the Declaration of inalienable rights that was now admitted to have been manfully and successfully sustained. Dr. Bloomfield, father of Governor Bloomfield of New Jersey, is said to have presided on that joyous occasion, which was celebrated by a public dinner, for which was provided a roasted ox—a circumstance that attests the general and cordial attendance of the citizens.

Who could have predicted the era of pro-slavery mobs against abolition meetings then? Who would have looked for biblical defences of slaveholding, from the high places of Princeton? Who would have believed that churches and pulpits, generally, throughout the country, would ever be closed against the discussion of slavery, for fear of “disturbing the peace of our Zion?” Who would have believed that anti-slavery agitation [activism] would ever have been regarded with abhorreuce, as adverse to “the perpetuity of our glorious Union?” What value could the patriots of that

-94-

day have attached to any union that was not cemented on the basis of freedom, and designed for its guaranty?

ABOLITION SOCIETIES.

It may be difficult to enumerate all the manumission and abolition societies of this period, or to fix [identify], accurately, the precise dates of their organization. The particulars that follow embody what we have at command.

Dr. Holmes, in his “American Annals,” says that the Abolition Society of Pennsylvania was formed in 1774, and was enlarged in 1787. Hildreth, in his “History of the United States,” says the Pennsylvania Society was the first. Edward Needles, in his “Historical Memoir of the Pennsylvania Society for the abolition of Slavery, the relief of free negroes unlawfully held in bondage, and for improving the African race,” says the first associated action in Philadelphia was a meeting of a few individuals at the Sun tavern in Second-street, April 14, 1775,*

when a society was formed “for the relief of free negroes unlawfully held in bondage.” The society met four times in 1775, and adjourned to meet in 1776; but, on account of the war, no meeting occurred till February, 1784, after which its meetings were continued till March, 1787, when the Constitution was so revised as to include prominently “ the abolition of slavery” as in the above title. Of this Society, Dr. Benjamin Frankiin was chosen President.

The New York “Society for promoting the Manumission of Slaves, and protecting such of tbem as have been or may be liberated,” was formed January 25, 1785, as before mentioned. Of this society, John Jay was the first President. On being appointed Chief-Justice of the United States, he resigned, and was succeeded by Gen. Alexander Hamilton, who held the office a few months, until, on, receiving an appointment in the Federal cabinet, he removed to Philadelphia, and soon after his place was filled by "Gen. Matthew Clarkson, the United States Marshal for New York, a very pious, good

____________________________________

* One year later than the statement of Dr. Holmes.

-95-

man, and belonging to a different species from the general race of slave-catching marshals.”*

May 5, 1786, the committee of the New York Society reported that a similar society was about to be established at Providence, Rhode Island. In 1788 the Pennsylvania Society addressed their corresponding members in Rhode Island, about vessels fitting out there in defiance of the laws against the slave trade. In 1791 the Rhode Island Society is alluded to as having memorialized [petitioned] Congress, in conjunction with the abolition societies of Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, Baltimore, Virginia, and two societies on the eastern shore of Maryland.

The Maryland Abolition Society was formed in 1789. The Connecticut Abolition Society in 1790; the Virginia Abolition Society in 1791. The New Jersey Society, “for promoting the Abolition of Slavery,” in 1792.

The Maryland and Virginia Societies had auxiliaries in different parts of those States.

There was also a society in Delaware. In 1794, ten societies met in convention in Philadelphia, and continued to meet annually, for a number of years afterwards.

Of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, Benjamin Franklin was chosen President, and Benjamin Rush Secretary, both signers of the Declaration of Independence, and the first-named just returned from the convention that drafted the

Federal Constitution. Among the officers of the Maryland Society was Samuel Chase, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, afterwards Judge of the United States' Supreme Court, and Luther Martin, a member of tho Constitutional Convention. Of the Connecticut Abolition Society, Dr. Ezra Stiles, President of Yale College, was the first President, and Simeon Baldwin was Secretary.

| “Among other distinguished individuals who were efficient officers of these abolition societies, and delegates from their respective State societies, at the annual meetings of the American Convention for Promoting the |

____________________________________

* MSS. by Hon. Wm. Jay.

-96-

| Abolition of Slavery, were Hon. Uriah Tracy, United States Senator from Connecticut; Hon. Zephaniah Swift, Chief Justice of the same; Hon. Cœsar A. Rodney, Attorney-General of the United States; Hon. James A. Bayard, United States Senator from Delaware; Gov. Bloomfield, of New Jersey; Hon. Wm. Rawle, the late venerable head of the Philadelphia bar; Dr. Casper Wistar, of Philadeiphia; Messrs. Foster and Tillinghast, of Rhode Island; Messrs. Ridgley, Buchanan, and Wilkinson, of Maryland; and Messrs. Pleasants, McLean, and Anthony, of

Virginia.”—Power of Congress, &c., pp. 30, 31. |

These Abolition Societies and the officers and members of them were not idle. They agitated the subject, circulated publications, and petitioned legislative bodies.

In 1786, John Jay drafted and signed a memorial to the Legislature of New York against slavery, and petitioning for its abolition, declaring that the men held as slaves by [unconstitutional] the laws of New York, were free by the law of God. Among the other petitioners were James Duane, Mayor of the City of New York, Robert R. Livingston, afterwards Secretary of Foreign Affairs of the United States and Chancellor of the State of New York, Alexander Hamilton, and many other eminent citizens of the State.*

Nor were petitions addressed only to the legislatures of the States in which the petitioners resided. The doctrines of moral and political non-intervention with the delicate subject had not then been discovered. The dogma that Congress has nothing to do with slavery in the States does not appear to have obtained general currency at that period. These statements are believed to express simple historical facts, and applicable up to a point of time after the Federal Constitution had been drafted, discussed, and adopted, and the Federal Government under that Constitution organized and put in operation. A few particulars will suffice to justify these statements.

Both the Virginia and Maryland Abolition Societies, at an early day, sent up memorials to Congress. We have not at hand the precise dates, nor is this important. The dates of the organization of these societies, particularly that of Vir-

____________________________________

* MSS. by Hon. Wm. Jay.

-97-

ginia, make it evident that their petitions were addressed to the new Federal Government. The Connecticut Abolition Society sent up a petition in 1791. The Society of Friends and the Pennsylvania Abolition Society had done so, still earlier, and their petitions came before the first Congress under the new Constitution, and were debated February 12th, 1790.*

These petitions were addressed to Congress. What could the petitioners have supposed that Congress had to do with the subject?

The Foreign Slave Trade, at that time, appears to have been interdicted [banned] by most of the States, in conformity with the original compact of l774, and was not resumed, even by South Carolina, as has already been stated, until 1802. And among the “compromises of the Constitution,” since claimed [later pretended], a prominent one, and the best authenticated, is that which prevented Congress from from interdicting the foreign traffic [slave trade], until 1808.

The cession of the District of Columbia was not accepted by Congress until July 16, 1790, some time after the presentation of the Pennsylvania petition. The seat of the Federal Government, then, and for some years afterwards, was at Philadelphia.

By the ordinance of 1787, slavery had been prohibitcd in the North Western Territory, and no one anticipated the admission of any new slave states.

What, then, was there for Congress to do, according to the doctrine of non-intervention now entertained [invented]? What was it that the petitioners asked? Against what did they petition? And where did it exist?

A copy of the Pennsylvania petition is before us, and portions of those from Connecticut and Virginia.

The Connecticut petitioners, (Pres. Stiles, Simeon. Baldwin, &c.) say:

| “From a sober conviction of the UNRIGHTEOUSNESS OF SLAVERY, your |

____________________________________

* Mr. Weld's pamphlet and the Liberty Bell give the date 1789, but Washington was not inangurated until April 30th of that year, and the “first Congress” commennced its first session, April 7th. Besides, the petition of the Pennsylvania Society, signed hy Benjamin Franklin, as published in the Liberty Bell, bears date of Feb. 3, 1790, and the Journal of Congress mentions its presentation, Feb. 12, 1790.

-98-

| petitioners have long beheld with grief our fellow-men doomed to perpetual bondage in a country which boasts her freedom. Your petitioners are fully of opinion that calm reflection will at last convince the world that THE WHOLE SYSTEM OF AMERICAN SLAVERY is unjust in its nature, impolitic in its principles, and in its consequences ruinous to the industry and enterprise of the citizens of THESE STATES.” |

The “Virginia Society for the Abolition of SLAVERY,” &c., in addressing the Congress of the United States, say:

| “Your memorialists, fully aware that righteousness exalteth a nation, and that SLAVERY is not only an odious degradation, but an outrageons violation of one of the most essential rights of human nature, and utterly repugnant to the precepts of the Gospel, which breathes 'peace on earth and good will to men,' lament that a practice so inconsistent with true policy and the inalienable rights of men, should subsist in so enlightened an age, and among a people professing that all mankind are, by nature, equally entitled to freedom. ” |

“The memorial of the Pennsylvania Society for promoting the abolition of SLAVERY,” &c., addressed “to the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States,” contains the following:

| “Your memorialists, particularly engaged in attending to the distresses arising from SLAVERY, believe it to be their indispensable duty to present this subject tn your notice. They have observed, with real satisfaction, that many important and salutary powers are vested in you, for 'promoting the welfarc and securing the blessings of LIBERTY to the PEOPLE of the UNITED STATES;'* and as they conceive that these blessings ought rightfully to be administered, WITHOUT DISTINCTION OF COLOR, to all descriptions of people, so they indulge thcmselves in the pleasing expectation that nothing which can be doue fur the relief of the unhappy objects of their care, will be either omitted or delayed.

“From a persuasion that equal liberty was originally the portion, and is still the birth-right of all men, and influenced by the strong ties of humanity and the principles of their institution, your memorialists conceive themselves bound to use all justifiable endeavors to LOOSEN THE BONDS OF SLAVERY, and promote a general enjoyment of the blessings of freedom. Under these impressions, they earnestly entreat your attention to the subject of slavery; that you will be pleased to countenance the RESTORATION TO LIBERTY of |

____________________________________

* This language is evidently taken from the Preamble to the Federal Constitution. “We, the people of the United States, in order to promote the general welfare; and scecure the blessings of liberty,” &., &c.

-99-

those unhappy men, who, alone, in this land of freedom, are degraded into perpetual bondage, and who, amid the general joy of surrounding freemen, are groaning in servile subjection; THAT YOU WILL DEVISE MEANS FOR REMOVING THIS INCONSISTENCY OF CHARACTER FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE, that you will promote mercy and justice towards this distressed race, and that you will step to the very verge of the power vested in you for discouraging every species of traffic in the persons of our fellow-men.

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, PRESIDENT.”*

PHILADELPHIA, Feb. 3, 1790.

[Federal Gazette, 1790.] |

DISCUSSIONS IN CONGRESS.

How were these petitions understood in Congress? How were they received and treated? Were they understood to look in the direction of a general removal of slavery, as well as the slave trade? Were the petitioners denonnced as fanatics and madmen? Was the application repelled as treason against the Constitution and the Union?

On the other hand, were there any who expressed a readiness “to espouse their cause”? The reader of the following extracts from the discussions, will judge.

In the debate on the petition from Pennsylvania, Mr. Parker, of Virginia, said:

| “I hope, Mr. Speaker, the petition of these respectable people will be attended to, with all the readiness the importance of its object demands; and I cannot belp expressing the pleasure I feel in finding so considerable a part of the community attending to matters of such a momentous concern to the future prospenty and happiness of the people of Amenca. I think it my duty, as a citizen of the Union, TO ESPOUSE THEIR CAUSE.”

Mr. Page, of Virginia (afterward Governor) “was in favor of the commitment. He hoped that the designs of the respectable memorialists [petitioners] would not be stopped at the threshold, in order to preclude a fair discussion of the prayer of the memorial. With respect to the alarm that was apprehended, he conjectured there was none; but there might be just cause, if the memorial was NOT taken into consideration. He placed himself in the case of the slave, and said that, on hearing that Congress had refused to listen to the decent suggestions of a respectable part of the community, he should infer that the general Government, FROM WHICH WAS EXPECTED GREAT |

____________________________________

* This was probably the last important public act of Frankin, who died the same year.

-100-

| GOOD WOULD RESULT TO EVERY CLASS OF CITIZENS,* had shut their ears against the voice of humanity, and he should despair of any alleviation of the miseries he and his postenty had in prospect. If anything could induce him to rebel, it must be a stroke like this, impressing on his mind all the horrors of despair. But if he was told that application was made in his behalf, and that Congress were willing to hear what could be urged in favor of discouraging the practice of importing his fellow-wretches, he would trust in their justice and humanity, and wait the decision patiently.”

Mr. Scott, of Pennsylvania: “I cannot, for my part, conceive how any person CAN BE SAID TO ACQUIRE PROPERTY IN ANOTHER;† but—enough of those who reduce men to the state of transferable goods, or use them like beasts of burden, who deliver them up as the patrimony or property of another man.‡ Let us argue on principles countenanced by reason and becoming humanity. I do not know how far I might go if I was one of the Judges of the United States, and those people were to come before me, and claim their emancipation [as in Somerset v Stewart]; but I am sure I would go as far as I could [to enforce common and constitutional law].”§

Mr. Burke, of South Carolina, said: “He saw the disposition of the House, and he feared it would be referred to a committee, maugre [in spite of] all their opposition.”

Mr. Smith, of South Carolina, said: “that on entering into this government, they (South Carolina and Georgia) apprehended that the other States, not knowing the necessity of the citizens of the Southern States, would, from motives of humanity and benevolence, be led to vote for a GENERAL EMANCIPATION; and, had they not seen that the Constitution provided against the effect of such a disposition, I may be bold to say they never would have adopted it.”

“In the debate, at the same session, May 13th, on the petition of the Society of Friends respecting the slave trade, Mr. Parker, of Virginia, said: 'He hoped Congress would do all that lay in their power to restore to human nature its inherent privileges, and, if possible, wipe out the stigma that America labored under. The inconsistency in our principles, with wbich we are justly charged, should be done away, that we may show, by our actions, the pure beneficence of the doctrine we held out to the world in our Declaration of Independence.'”

“Mr. Jackson, of Georgia, said: 'IT WAS THE FASHION OF THE DAY TO FAVOR THE LIBERTY OF THE SLAVES. * * * What is to be done for compensation? Will Virginia set all her negroes free? Will they give |

____________________________________

* Here, again, we find the negro slaves expressly designated as citizens.

† Another blow at the idea of the legality of slavery.

‡ How does this harmonize with the [falsely alleged] Constitutional obligation of delivering up fugitive slaves?

§ A pregnant hint of the speaker's impression of the duties of the Federal Courts [to enforce common and constitutional law].

-101-

| up the money they have cost them, and to whom? When this practice comes to be tried, then the sound of liberty will lose those charms which make it grateful to the ravished ear.'"

"Mr. Madison, of Virginia: 'The dictates of humanity, the principles of the people, the national safety and happiness, and prudent policy, require it of us. The Constitution has particularly called our attention to it. * * * I conceive the Constitution in this particular was formed in order that the Government, whilst it was restrained from laying a total prohibition, might be able to give some testimony of the sense of America, with respect to the African trade. * * * It is to be hoped, that by expressing a national disapprobation of the trade, we may destroy it, and save our country from reproaches, and our posterity from the imbecility ever attendant on a country filled with slaves.

"I do not wish to say anything harsh to the hearing of gentlemen who entertain different sentiments from me, or different sentiments from those I represent. But if there is any one point in which it is clearly the POLICY OF THIS NATION, so far as we constitutionally can, to vary the practice obtaining under some of the State Governments, it is this. But it is certain that a majority of the States are opposed to the practice."—Cong. Reg., v. i., pp. 308-12; Weld's Power of Cong., &c., pp. 30-32. |

There may be some difficulty in apprehending, clearly, the import of some of the expressions used in this debate. This may be owing to our making a broad distinction, now, which seems scarcely to have been recognized at all, then, between the slave trade and slavery. It seems to have been taken for granted that the prohibition of the former would involve, virtually, the extinction of the latter. Georgia had desired a respite of twenty years, which, by the Constitution, had been granted. Thus far the hands of Congress were tied. Thus, at least, it was understood by the speakers. This was the compromise claimed. This exposition of the position of the speakers, if it be correct, enables us to understand the drift of their arguments. What then do we find?

First, we have the presentation of petitions, some of them said to be in respect to the slave trade, others of them (including that of Dr. Franklin) as evidently bearing upon "SLAVERY" itself, desiring for the slaves their "restoration to liberty," and that Congress would "devise means," in some way, for "removing this inconsistency from the American

-102-

character. The two descriptions of petitions appear to have had the same object, and to have been received and considered accordingly.

Next, we have two gentlemen from Virginia decidedly "espousing the cause" of the petitioners, followed up by a representative of Pennsylvania, on the same side.

Then, we have a specimen of the opposition, from South Carolina and Georgia; and finally, an effort, by Mr. Madison, to reconcile the difference between the parties, though strongly leaning to the side of the petitioners, and declaring that he represented, for his constituents, those sentiments.

The main object of the slave party, seems to have been to stave off present action. The House, and the Country, they saw and acknowledged, were disposed to be against them—disposed to liberate " the slaves." They pleaded the constitutional compromise, that is, the postponement till 1808. Yet they raised the question of compensation, as much as to intimate that if the country was ready to meet their demands in this respect, they might waive their constitutional objections. And this was then the extent of South Carolinian, and Georgian opposition!

"Humanity and Benevolence," they admitted, was on the side of the petitioners, and of those who might "vote for a general emancipation." Not a word of the dnngers of turning the slaves loose. Not a single threat of dissolving the Union. Not a lisp of the sacred guaranties of the Constitution, of the obligation to protect and extend slavery!

From the advocates of liberty, in the House, then, we hear no concessions of the compromises of the Constitution. Those, they left in the hands of their opponents, and in the hands of the illustrious pacificator between the two parties. And even his (Mr. Madison's) speech, would be accounted a radical abolition harangue, were it uttered in Congress now. It is instructive to ponder these contrasts. We need to be disabused of our vague impressions and educational prejudices, if we would understand the relation of slavery to our political institutions, as at first established.

-103-

Little incidents, often, more than imposing official documents, and public records, reveal public character and assist us to understand the spirit and temper of a particular age or people. "In 1791, the university of William and Mary, in Virginia, conferred upon Granville Sharp, of England, the Degree of Doctor of Laws."*

Who was Granville Sharp [1735-1813]? And by what discoveries in the sublime science of jurisprudence had Granville Sharp, a clerk in the ordinance department of Great Britain, commended himself to a Virginian University, for so distinguishing an honor? The reader of the preceding chapters understands. Granville Sharp had discovered and announced the utter and absolute illegality of slavery under the ægis of the British Constitution, and under the jurisdiction of English Common Law. With this discovery he had enlightened the British mind, had reversed the legal decisions and opinions of York and Talbot—of Blackstone and Mansfield.

Without a seat in the Court of King's Bench, nay, without the credentials that could entitle him, by the usages of Court, to stand up in its presence and plead a cause, Granville Sharp, by the simple force of his lofty intellect and indomitable and righteous purpose, had laid his hand on that Court of King's Bench, and compelled it to do (unwillingly enough) his bidding, in the decree that "slaves cannot breathe in England." More than tills—Granville Sharp, perceiving that this decree was binding on the colonies of Britain, as well as on the mother country, had solemnly admonished the British prime minister of his high responsibilities in this respect, and with all the majesty of a holy prophet had charged him, on the peril of his soul, to lose no time in suppressing slavery in America. This was the high merit of Granville Sharp.