| This site reprints Alvan Stewart's 1845 book, Legal Argument For the Deliverance of Persons from Bondage.

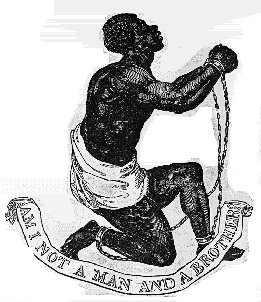

During the pre-Civil War slavery era, there were a number of abolitionists, e.g., James Otis (1761), William Mansfield (1772), John Adams (pre-1776), Samuel May (1836), Salmon P. Chase (1837), George Mellen (1841), Lysander Spooner (1845), Benjamin Shaw (1846), Joel Tiffany (1849), Lewis Tappan (1850), William Goodell (1852), Abraham Lincoln (1854), Edward C. Rogers (1855), William E. Whiting, LL.D., et al. (1855), Rep. Amos P. Granger (1856), and Frederick Douglass (1860), who did lectures or books on slavery unconstitutionality. They showed that pursuant to common law, centuries of precedents, and constitutional and legal principles dating back to the Magna Carta (banning detentions without due process, e.g., without charges verified by conviction in a jury trial), slavery was unconstitutional, and illegal as well, pursuant to anti-kidnaping laws. Preparatory to your reading this site, reading the historical and constitutional law overview and/or some or all the above authors' writings, is recommended.

To go to the "Table of Contents" immediately, click here. The cases were State v Post and State v Van Beuren, 20 (Spencer) NJL 368 (May 1845) aff'd 21 (1 Zab) NJL 699 (Jan 1848). Stewart's speech provides in a brief overview, some of the many legal principles making slavery unconstitutional. In this lengthy speech of about 33,000 words, that took some time (11 hours estimated) to deliver it, he covers a sweeping range of material. He cites the major precedent, the 1772 Somerset case. His section on constitutional due process dates from at least eight years before, 1837. Citing Bible precedents in court was still done in that era, witness his citing the Mosaic Exodus and the Ten Commandments. To recreate the speech, and persuasive effect, you may wish to speak aloud some or all of it. |

Supreme Court of the State of New Jersey at the May Term, 1845, at Trenton, for the Deliverance of 4,000 Persons from Bondage by Alvan Stewart (New York: Finch & Weed, 1845)

THE public will not expect a preface to a disquisition on Constitutional Law, which can go far to encourage them, in the perusal of a legal argument; but when that public are informed that the argument was not to change the title to a farm, or test the Constitutionality of a bank charter, but that it was made for the deliverance of four thousand human beings from bondage, and to overthrow the institution of slavery in the State of New Jersey, further attempts at apology or to propitiate their kind perusal, would seem unnecessary. Several distinguished gentlemen of the bar have been so kind as to wish to see this argument in a more perfect form than could be expected from the desultory notes of a reporter, which only glanced at some of the most important topics which formed the basis of discussion; to meet which desire, and contribute a single mite to the deliverance of my countrymen from slavery, it is hoped, will insure the reading of the following pages. LEGAL ARGUMENT FOR DELIVERANCE FROM BONDAGE 1. Introduction . . . [I]n substance . . . general demurrers were put in, alleging the institution of slavery was abolished, and that the returns did not state sufficient authority to authorize the defendants to hold said persons. To which there was a joinder in demurrer. . . . The following pages are intended to be the substance of the argument and reply of ALVAN STEWART, Esq., of New York, who appeared for the slave and servant, as their Counsel. The first article of the new Constitution of New Jersey, of September, 1844, is entitled "RIGHTS AND PRIVILEGES." "All men are by nature free and independent, and have certain natural and unalienable rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing and protecting property* and of pursuing and obtaining safety and happiness." It was supposed there were from seven hundred to one thousand slaves, and from twenty-five hundred to three thousand servants or more, whose liberties were involved in the argument and decision of these causes, as well as the institution itself. ALVAN STEWART, Esq., arose and invoked, as he said, the kind consideration of this Court, while he endeavored to break into a new, and almost uncultivated region, to explore and investigate the long neglected rights of man to his own body and soul. The Courts of our country had sounded the depths of human learning, and all the vast stores of history, and the remains of antiquity had been overhauled, sifted and analyzed, with metaphysical sagacity, to determine with judicial accuracy, all the rights which men had to property, lands and tenements, corporeal and incorporeal. Everything in the shape of human acquisition had been again and again labored and belabored by the highest talents of the land, until learning and genius could do no more, to add to man's possessions; while the great right of man to himself, while innocent self-ownership, under all circumstances, is a great question, which has rather been grazed than lilted up, shunned than embraced, or duly considered, in all its mighty amplitude, and its solemn importance; and then only at distant periods of time, and under the greatest disadvantage in point of time, place, position and circumstance. The controversies about lauds and estates, and the personal rights of freemen, with all the subtle ramifications of the schoolmen, of various legal questions of our age, have been pressing the highest judi- cial forums of our land for decision, and constitute much of the drudgery of counsel, and labor of the judges. A modern legal opinion of counsel or judge is, that it is his opinion that he has clearly discovered what was the opinion of Chief Justice Mansfield, or Lord Thurlow, on this question, when Lord M., or Lord T. saw fit to express an opinion on this subject. Considering the mighty questions of human liberty placed under the control of twenty-seven State Constitutions, their laws, and the Federal Constitution and acts of Congress, and the ten thousand forms in which human liberty may be abused, from the most horrible slavery, to the slightest invasion of a trespass; it seems passing belief, to be told, there is not one volume of reports, arguments and decisions, touching the great inalienable rights of man, invaded as they are, by communities, states and individuals, as a regular commerce carried on in crushed and violated human rights, assaulted in every direction, overthrown, trodden under foot as they are, at every step and angle of passing life. The attention of our countrymen seems to have been turned to the contingencies and appurtenances of our race, rather than to man, and the elevation of the race itself. Congress has shown more anxiety to protect the hats, the boots, and the coats which men wear, than the heads they cover, the bodies they surround, and the feet they enclose. That grave assembly can dispute from Christmas to dog-days, about the Tariff, Protection, Free Trade and Revenue, while a petition to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia, to give a man to himself, a wife to a husband, and children to their parents, is received with profound astonishment as a moral anomaly, and when the house has recovered from its surprise, the petition being so completely at right angles with the course of a republican Congress, that unread, unprinted, undebated, and undecided, it is ordered to lie upon the table, until the clerk removes it to its sepulchral silence in one corner of the Capitol, to rest with the other entombed memorials of a nation's dishonored humanity. Nothing has been held so cheap as our common humanity, on a national average. If every man had his aliquot proportion of the injustice done in this land, by law and violence, the present freemen of the northern section would many of them commit suicide in self-defence, and would court the liberties awarded by Alt Pasha of Egypt to his subjects.

Yet these laws and constitutions should have long ere this felt the weight of judicial pressure, and their good or evil been made prominent to the men of America, and the breadth and depth of the stream of national justice ascertained, so that we might know the exact distance between our self-glorifications, or our pompous anniversaries, and the pretended magnitude of our personal liberties, as compared with the stern and inexorable mandates of judicial decrees; or what was the difference between an abstract dogma of liberty, and a practical decision of tyranny. Alas! said Mr. S., how vast the distance between an abstraction and a practicality! Oh! when, said Mr. S., shall we see that glorious day, when the lion and the lamb shall lie down together? that day when the law, with its mercy, shall be extended to all, when none shall be so powerful as to override its injunctions, none so low as to fall beneath its merciful protection, defending all in their possessions; the rich man in his castle, the poor man in his liberty, and the value of his labor, whether in the wilderness, or the city, on the highway or in the closet; let this law of liberty brace the strong man on his journey, and its precious breathings fill the lungs of the infant in the cradle. Oh! for the glorious day when we shall have freedom for all, wages for labor, education for all, mercy to all, justice for all, and God's religion in all! Mr. S. said it was a horrid thought, that in the 19th century, there should be found educated men, who were so weak, or so ignorant, as to suppose the title to the great inalienable God-given rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, depended upon the complexion of a human being, whether white, black, brown, red, or in combinations of these, with curled or long hair, thick or thin lips; the body is the casket, the soul, the immortal mind is the jewel. The jewels are homogeneous, the caskets may be infinitely diversified. To deny the existence of the jewel, from the caskets being more or less plain than some other we have seen (when we know the jewel is within), is not more absurd than to make a man's right to liberty depend upon the color of his skin. But, said Mr. S., such are the raw material of apologies for gross wickedness, and the vileness of the material is never improved by its manufacture. The raw material, its manufacture, the manufacturer, and the consumer of such strange productions, ought to be bottled and hermetically sealed, where they might be seen through a glass case as certain lusus naturæe, or as a calf with two-tails and no head are seen in some of our museums. In order, said Mr. S., to understand the blessings which the new constitution of this State confers on the subject of liberty, it may not be amiss to look, for a few moments, at the past ages of the world, on the subject of slavery, and see how the men of antiquity saw and treated this terrible perversion of human rights. The ancient world, before the advent of our blessed Saviour, was filled with this awful crime. All pagan lands abounded with idolatry and slavery. But the glorious new religion, wherever it made a lodgment, amidst cruel scourgings, the faggot and the flame, the block and the cross, the dungeon and the gibbet, obtained the ascendency; and this dreadful institution fell before the mercy of the cross. From the conversion of Constantine in the 4th Century, until the 12th, Christianity fought her victorious battle with slavery, and came off conqueror and drove it from the entire regions of continental Europe, or wherever Christianity obtained a foot-hold throughout Christendom. To be sure, said Mr. S., there existed, owing to the Feudal Law, a sort of serfdom, in some countries, which was different in appellation and character from the chattel-hood of slavery. Time fails, said Mr. S., to tell how the various devices of Pope, Pontiff, Bishops, ecclesiastical councils, decrees of councils, of kings, diets and parliaments, accomplished during what is called the dark ages—this most glorious work. Said Mr. S., but the ever-memorable year of 1492 came for ever to be reckoned the most wonderful in the history of our race since our Saviour was born,—a new world was discovered by Christopher Columbus, the grandest man of his race. The human passions burst into a mighty flame, fed by the accursed thirst of gold, discovery, and conquest. The peaceable and inoffensive red man of the islands of the Antilles was forced as slaves to do work in the fields and in the mines; and that age of innocent red men, a whole generation of which found that mercy in death, which their Spanish conquerors denied them. The good [Priest Bartolomé de] Las Casas [1474-1566], moved by a considerate sympathy for the red man, [supposedly] absurdly recommended to his prince and country, to repeal slavery as to the red man who could not endure its cruelty, and in lieu, abduct and kidnap laborers from the burning tropics of Africa; and from 1520 this dreadful wound was opened in the side of Africa, which has continued from year to year, and from century to century, to flow on without intermission, until this very hour. For more than 300 years has Africa been despoiled of her people by the kidnappers from the nations of Christendom, until Christendom in three centuries had made it the law of nations to rob the men of Africa of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and made and revived the extinct law of slavery, and with armed bands marched into defenceless villages on the Senegal and Gambia, set their habitations at midnight on fire, and with pistols, swords, fetters, and ropes, pursued and overtook the distracted people and bound and sent them to this continent amidst hunger, thirst, contagion, disease, and death, the survivors in the pirate's ship, and in a land of strangers, they were sold to drag out life on the plantation of the haughty, the thankless, and the cruel. By such deplorable means has this continent fought against her own prosperity. Mr. STEWART then said he had two cases in his mind which illustrated what all knew respecting slavery, and few whose opinions were entitled to respect would dare deny them. Said Mr. S., lifting his head and turning to the north-east, directing all to look, and see what they could behold on the last day of November, 1620, on the confines of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, Lo, I behold one little solitary tempest-tost and weather-beaten ship, it is all that can be seen on the length and breadth of the vast intervening solitudes, from the melancholy wilds of Labrador and New England's iron-bound shores, to the western coasts of Ireland and the rock-defended Hebrides, but one lonely ship greets the eye of angels or of men, on this great thoroughfare of nations in our age. Next in moral grandeur, was this ship, to the great discoverer's; Columbus found a Continent; the May-flower brought the seed-wheat of states and Empire. That is the May-flower, with its servants of the Living God, their wives and little ones, hastening to lay the foundations of nations in the occidental lands of the setting sun. Hear, the voice of prayer to God, for his protection, and the glorious music of praise, as it breaks into the wild tempest of the mighty deep, upon the ear of God. Here in this ship are great and good men. Justice, mercy, humanity, respect for the rights of all; each man honored, as he was useful to himself and others; labor respected, law-abiding men, constitution-making and respecting-men; men, whom no tyrant could conquer, or hardship overcome, with the high commission sealed by a spirit divine, to establish religious and political liberty for all. This ship had the embryo-elements of all that is useful, great and grand in Northern institutions; it was the great type of goodness and wisdom, illustrated in two and a quarter centuries gone bye; it was the good genius of America. But, look far in the south-east, and you behold on the same day in 1620, a low rakish ship hastening from the tropics, solitary and alone, to the New World, what is she? She is freighted with the elements of unmixed evil, hark! hear those rattling chains, hear that cry of despair and wail of anguish as they die away in the unpitying distance. Listen to those shocking oaths, the crack of that flesh-cutting whip. Ah! it is the first cargo of slaves on their way to Jamestown, Virginia. Behold the May-flower anchored at Plymouth rock, the slave ship in James river. Each a Parent, one of the prosperous labor-honoring, law-sustaining institutions of the North; the other the Mother of slavery, idleness, lynch-law, ignorance, unpaid labor, poverty, and duelling, despotism, the ceaseless swing of the whip, and the peculiar institutions of the South. These ships are the representation of good and evil in the New World, even to our day. When shall one of those parallel lines come to an end? Mr. STEWART then proceeded to the definition and origin of the word slave. He cited the encyclopedia under title, slave, as authority. The word, according to Vossius, is derived from sclavus, the name of a Scythian people, called the Sclavoni. The Romans called slaves servi, from servare, to keep or save, being such as were not killed in battle, but were saved, to work or yield money. A slave bred in a family was called verna, hence our word vernacular, or the slave's tongue. A Roman slave being set free, took the cognomen of his master for his sur or sir-name, and his slave name for his Christian—hence, our surname means the name of the lord or sir. So curiously has slavery interwoven itself in the affairs of men, that all men are made most singularly to feel the disgrace of the institution in their paternal name. The Romans had those called mercenarii, who had been rich, but having become poor, sold themselves for a time. The Greeks had those called Prodigals, who, having lost their estates by their extravagance, were sold to discharge their debts by law, for a longer or shorter time. Delinquents to the revenue, or unfaithful subtreasurers of the Roman Empire, were sent to the oar as slaves. But [Cornelius] Tacitus [55 A.D. - 117 A.D.] describes the most remarkable slaves, De Moribus Germanorum, called enthusiasts, who were gamblers, who having staked and lost their money, goods and lands, finally staked their own bodies, and if they lost, the strong and the young lifted up their hands and received the fetters thereon, from the aged and weak, and were marched off forthwith to the slave market and sold by the winner as slaves for life. This was done under the code of a gambler's honor. Those are the two kinds, among the ancients, of slavery, voluntary and involuntary. Some think slavery did not exist before the Flood. But Alexander Pope thinks differently, and says:

A man has no right to sell himself, and if he had, he could not bind his posterity. A man is not allowed to kill himself.—Blac. Book 1, C. 14. Montesquieu Spirit Laws, B. 15, C. 2, and 6.—Both say, if a man might be taken in war and made a slave, this war-right of the captor could not extend to the captive's posterity. This alone would abolish slavery.

The Romans exercised the power of life and death over a slave. So do slaveholders in the United States under certain circumstances; if the slave refuse to work, he, the master, may, by slave law, whip and beat him until he is dead, unless he submits to go to work; or if a slave attempt to run away, and the master commands him to stop, and he refuses, the master may shoot him down, and the slave laws of more than ten States say, amen. The Romans were very cruel, and had an Island in the Tiber, where by law, they might send old, useless and sick slaves to starve to death or die. It is said as an evidence of slavery's hardening of the heart to human suffering, that the elder Cato sold his superannuated slaves for any price rather than maintain them. The Romans had slave dungeons under ground, called "ergastula," where the slaves were worked in chains. The same in Sicily, which country was cultivated by slaves in chains. Eunus and Athenio excited an insurrection of 10,000 slaves and broke up the dungeons.

It was justly said by that great lawyer and civilian, Mr. [Francis] Hargrave [1741-1821], the counsel of the slave Somerset, though greatly aided in his brief by that eminent philanthropist, Granville Sharp [1735-1813], "that slavery corrupts the morals of the master by freeing him from those restraints so necessary for the control of the human passions, so beneficial in promoting the practice and confirming the habit of virtue."It is often dangerous to the master, as exciting implacable resentments on the part of the slave. Said Mr. STEWART, slavery communicates all the afflictions of life to its victim without leaving scarce any of the pleasures; it depresses the excellence of the slave's mature, by denying to the slave the ordinary means of improvement and elevation in the social scale of existence; it brings forth the gross, malignant, cruel, mean, deceitful and hypocritical portions of human nature, without a counterpoise or a power of suppression. The slave is always the natural and implacable enemy of the State, he owes it nothing but deadly hate. Said Mr. S., instead of the Constitution and the laws being his shield and his inheritance, they are employed to strip him of his natural rights, of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, existing antecedent to all human compacts; and what should be employed for his protection and defence in the shape of law, is used for his prostration and destruction. It is the element of constant fear to the family and the State, and is therefore real weakness to the State from the constant apprehension from insurrection at home, or invasion from abroad, when it is always expected the slave will range himself in the ranks of the invader of the land. The slave has no country, no real home for which he will fight. Judge of the surprise of General La Fayette, said Mr. S., when on the first day of being introduced to the American Congress in Philadelphia, in the summer of 1777, he listened to the extraordinary request of South Carolina to be released from raising and equipping the quota of troops designed by Congress to be raised by that State as her proportion in the eventful struggle of the Revolution, on the ground if she spared that number of troops from the State, it was feared that there might be a servile insurrection, that it was necessary the troops should remain at home to restrain a domestic enemy in her own bosom. If all the States had been under the weight of slavery like South Carolina, our Independence could never have been achieved. Such States as South Carolina may bluster and threaten their brethren in time of peace with nullification and revolution, but when war comes, her power to act out of her own territory will be in the inverse ratio of the noise and threats she made in time of peace. The enemy of her own household will furnish a good market, not only for her capabilities but her courage. If the home market is the best one, she will find one at her own door, as ample as her productions may be abundant. In the late war [of 1812], about midsummer of 1814, this nation, said Mr. S., was overwhelmed with shame, grief and astonishment, at the [24-25 August 1814] capture and sack of the city of Washington [D.C.], by a body of British troops, soldiers, sailors and marines. The public authorities had sufficient notice of the enemy's intention, the militia of the three cities of the District [of Columbia], and of the surrounding counties in the adjacent portions of the old States of Virginia, and Maryland, could have driven the British force into the sea, had not a report been universally circulated on the morning of the battle, and on the battleground at Bladensburgh, that the slaves of the District and of the adjacent counties, from which the militia were drawn for the defence of Washington, were to rise that day in insurrection during the absence of their masters.

Washington, and at last the retreat became a general rout; each man having his mind on the danger he feared in his own house or plantation from the insurrection of his slaves, rather than the immediate work of defending the Capitol of the nation.

This [Ed. Note: meaning, freeing the slaves pursuant to precedents], said Mr. S. [Ed. Note: defending what he was requesting, mass-slave-freeing, 4,000 in that area alone], is a perfect solution of that disgraceful affair. It [Ed. Note: meaning, the abandonment of the Capitol, due to slavers being more concerned to keep their slaves subjugated, than to defend the nation, which slavers often savaged], was the natural consequence which the weakness of a servile population creates, and the fear in a day of adversity which it will inspire. Mr. S. said he learned the cause of our disaster [defeat at Washington] in 1818, while going over the ground of this disgraceful retreat, with a General, who was a Brigadier on that mortifying day, who assigned the above reasons to Mr. S., as the cause of this most shameful result.

Said Mr. S., in the sixth year of the reign of Edward III., 1334, a law was enacted declaring that all idle vagabonds should be made slaves, fed on bread and water or small drink, and refuse meat, and should wear an iron-ring around their necks and legs, and should be compelled by beating, chaining and otherwise, to perform the work assigned, were it never so vile; the spirit of the English nation could not brook this, as applied to the most abandoned rogues, and repealed the law in two years after its enactment. But nothing places the judiciary of England on higher ground, than its patient work in extirpating villeinage [semi-slavery] from England. It was an institution connected with the feudal system, and the Norman Conquest of 1066, and the other conquests obtained in previous ages, and was nearly allied to slavery, in everything but the name, so that it is supposed at one period, there was not less than three quarters of the population of the [English] kingdom, who were either villeins regardant, or villeins in gross. The dishonor of such a state of things has been so deeply felt by thousands, who are descendants of these bondmen in England, and who now rank high in the scale of society, that there is rather a desire to conceal than reveal the odious state in which our ancestors existed; therefore, David Hume [1711-1776] and Sir William Blackstone [1723-1780] are very niggardly in dealing out information on an infamous and obsolete institution, so humiliating to our ancestors, and humbling to their descendants. But, said Mr. S., to understand the terrible hardships endured and suffered by our ancestors, for many generations, and the glorious way of their deliverance by the judges of England, may furnish us with valuable deductions, which may be applied to solve any difficulty growing out of the causes under consideration, by learning what use a court tnay make of law to establish justice. A villein in blood and by tenure was one whom the lord might whip and imprison. The villein could acquire no property except for the lord. "Quidquid acquiritur servo, acquiritur domino." A villein regardant passed with the land of his lord, on which he lived as a kind of property like the trees, but might be severed and sold when the lord pleased.—Co. Littleton 117 a. If he was a villein in gross, he was an hereditament, or chattel real, according to the lord's interest, being descendable to the heir, when the lord was absolute owner of the soil, and to the executor, when the lord was possessor for only a term of years. The common law held if both parents were villeins, or the father only, the issue were villeins. The child at common law followed the condition of the father, Partus sequitur patrem; while the civil law held, Partus sequitur ventrem. Therefore, it was a departure from all principle, for the slaveholders of the United States, who if they inherited anything from England it was the common law, to substitute the principle of the civil law, because they could make more money by it, and say the child in slavery should follow the condition of the mother, when the common law said it should follow the father! But why reason on a subject, when brute force and selfishness stand in the place of right reason and truth? Had, said Mr. S., the doctrine of the common law been followed, slavery from its mulattoism a significancy of the times, would have been in its last quarter. The object, said Mr. S., of drawing this all but obsolete learning from past centuries, was not to make a public parade for the sake of its strangeness; but to show in the great struggle, in past ages, between slavery and liberty, how the judiciary of England conducted itself in those encounters between the powers of light and darkness. The Courts of Law in the British Isles, from the [1066] Conquest down, employed every intendment of humanity, every device, every fiction, in behalf of the unfortunate serf. One rule was for the court always to presume in favor of liberty; but in some thirteen States of our Union, if a man is of African descent, he is presumed a slave, until the victim proves a negative. In England the onus probandi lay on him who asserted slavery or villeinage to prove it. If a villein prosecuted a writ of Homine Replegiando against his lord, on the trial the lord had to prove affirmatively the plaintiff was his villein, and the villein, though the plaintiff, might stand still in court till that was done by the defendant. The lord's remedy for a fugitive villein was the writ Nativo Habendo, or Neifty. If the lord seized the villein by his writ of Nativo Habendo, the villein procured the writ of Homine Replegiando, or Libertate Probanda. By the writ of Nativo Habendo, the master asserted slavery, and if the master was once nonsuited, he could never sue the serf again [re res judicata], and the villein might plead the record of nonsuit as a perpetual bar. Not so, if the poor villein was nonsuited on the writ of Homine Replegiando, or Libertate Probanda. He might sue again for his liberty, and the record of nonsuit, if made ten times or more against him, could never be pleaded or used against him. The slightest mistake on the part of the lord, or accident, was laid hold of by the court to defeat the recovery of the lord.—Somerset's Case, 20th vol. of Howell's State Trials. So [likewise] this honorable court of New Jersey should do, said Mr. S., under the new constitution of this State—the constitution adopted by the people in 1844. This court, in accordance with the noble example of England's judiciary, should make every intendment in behalf of your bondmen, as between the selfish and cruel demand of slavery and the ceaseless cry of liberty. Give the slave the benefit of every sensible doubt, which may cloud the mind of this Honorable court. Sueing, or being sued by a villein, freed him. The lord's granting him an imparlance, manumitted him, or asking an imparlauce of the villein did the same. Almost, said Mr. S., the last case of villeinage reported, was near the year 1600, on the accession of James I. Crouch's case is reported in Dyer. All of these obstructions thrown in the way of this sort of slavery, are most interesting legal relics of servitude, showing the meta-physical dress in which it was clothed by our subtle and ingenious ancestors. These were patterns of extinct fashions of opinions, now only to be found in the ponderous tomes of antiquity, garnered up in the library of the legal antiquarian; as the visors, steel and brass armor, of the 10th century, disclose to us the mode and appearance of the knights on the field of battle in the days of chivalry. To establish villeinage, the villein must be proved such by two other male villeins, ex eodem stirpe, from the same stock, or the villein might confess in open court, being a court of record, that he was one. The female villein was not allowed her testimony to prove a man a villein. A villein was called nativus, as well as villanus, from the lord's villain, nativus from being found on the soil—a native. The lord, on declaring on a writ nativo habendo, had to bring his two witnesses with him at the same instant he declared, and if he did not, the villein went for ever free. A man might plead bastardy, in himself, father, grandfather, or ancestor, and if the plea be true, that alone manumitted the villein, for the filius nullius est filius populi. For if there was a link of illegitimacy, it set the line of descendants from the bastard free, because the lord could not show that he was the son of his bondmen in particular. Another plea of the villein was called adventiff by the Norman French Law, showing that a person was born off from the manor, and if true, it set the man and his descendants free. Said Mr. S., Sir Thomas Grantham, about the year 1684, bought a monster [Ed. Note: person with birth defects] in the East Indies, and brought him to England as a show. The monster had growing on his breast, the entire parts of a child, except its head. The monster being carried through the kingdom as a show, was baptized, and he brought a writ of Homine Replegiando against his master, and was set free. 3 Mod. 120. Said Mr. S., I have done with villeinage in England,—such in a dark age was the view which learned jurists and 'judges took of this important matter. The judiciary in many countries have been, at different periods of civilisation, the last branch of human government, to feel the force of popular opinion, in behalf of liberty, or employ its power in accelerating the march of freedom, or the overthrow of strongholds of fortified oppression. It is not, said Mr. S., a matter of complaint that the judiciary is the hold-back power of the State, or conservative in its character, but with all that, it has a high mission to discharge on the part of liberty. And the English judiciary have shown the world during those dark ages what they understood to be contained in their commissions, touching England's bondmen, even, under the iron rule of the haughty Norman [William the Conqueror, 1066] and his imperious descendants, who, by rights of conquest, and by the subserviency of supple parliaments connected with the agency of the Feudal System, had reduced four-fifths of the inhabitants of England to the condition of villeins regardant, and villeins in gross, attached to the soil, or the person of some grandee of the realm, as slaves, whom their lord might scourge, sell, or transfer with the soil, or at will. The judiciary of England became the Temple of Mercy to which these unfortunate bondmen cast their imploring eyes for relief through a succession of five cruel centuries, during eighteen generations of men The courts of English law during this long period, employed all the subtleties, fictions, and presumptions, inwhich the English Law abounds, in behalf of the liberty of these grossly injured men, so that at last, the sublime moral spectacle was presented to this world, of many unrepealed statutes, and the common law still in full force in favor of villeinage, while the bloody useless fetters hung on the tyrant's dungeon walls, but the last bondman of the three-fourths of the population of a mighty kingdom was enfranchised from captivity by force of England's glorious judiciary alone. The king, and iron-mailed barons, the landowners, and man-holders, were foiled, and their prey taken from their power by the resolution of the judges, who, being determined, did administer justice through the law. Montesquieu says that Aristotle, in reasoning to sustain slavery as derived from war, cites authorities from barbarous ages, and appears in this matter as unphilosophical as he does in the nature of the thing. The war-power to be the source of a right, when the war is prosecuted for no other motive except the value of the captive, is as rational as to give the robber title to his spoil, because he had the courage to take it—making a crime the most bold and daring, the parent of a civil right. Behold bleeding Africa, for three hundred years her bleeding side has flowed, and yet flows on, unstaunched by the humanity of the Nations. Behold this accursed crime which has crawled up with beastly impudence, and enthroned itself as one amongst the laws of Nations. Laws of Nations! What was this law of Nations?

Russia, Prussia, Holland, Austria, England, France, Sardinia and the United States, in the last forty years, as it regards themselves, by treaty and legislation; have abolished their respective portions in this frightful law of Nations, while Spain, Portugal and Brazil, three of the basest kingdoms of earth, are now retrograding into the darkness of barbarism and infamy, and without competition are now almost the exclusive proprietors of this law of Nations audits abounding criminality. Look at Spain three hundred and fifty-three years ago, as she stood on the day of Columbus' discovery, head and shoulders above the powers of Europe. Conquest, avarice, slavery and idleness, which she introduced to the New World, re-acted on her, and in our day, she has been stripped of her mines, her provinces, viceroyalties, kingdoms and one half of a continent, and is now reduced to the Island of Cuba, with its crimes of flowing blood, slavery, idleness and avarice; these relatives have been punished in so signal a manner, in the case of Spain, by Him who rules the destinies of Nations, that to deny it, is a proof that our ignorance is only surpassed by our infidelity. The Court will pardon me in these remarks, which in the first instance may appear remote from this question, yet when we consider the character of the human mind, they will all be found to bear on the great question in the Constitution of this State. What do we mean by liberty and independence? [It is] Infinitely absurd to say, a man has power even in himself, by contract, to dispose of his own liberty and all the rights he possesses. Society has claims on him, his wife, his children, and his God, which he cannot cancel by selling himself to another. Yes, coming generations have a voice in the question. He has no more right to sell his body than he has to commit suicide, for, by so doing, he passes from manhood to thing, or chattel-hood, and becomes a piece of breathing property. The great rights of manhood are not given to us by our Creator, to give, sell, and barter away. The powers of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, cannot be resigned to a power inferior, to that of the one, from whom they have been received. As to consideration that might be given for those God-inherited rights, described in your Constitution, said Mr. S., as unalienable, who is rich enough to buy them, who is able to make title to them? Suppose that some Crœsus owned this continent, and the mines of Golconda, and should offer them to me to become his slave, according to the laws of South Carolina and Louisiana; at the same instant, he executes for the consideration of my person, a deed of the continent and mines to me. and I execute to him a deed of my body. The purchaser of me, by the operation of the slave laws, instantly becomes repossessed of what passed to me by grant, under the maxim that the slave and all he hath, or may find or acquire, belongeth to the master, therefore, I the slave would say the consideration having failed, and by operation of law, my master having become reseized of his continent and mines, I am free again. Thus, it would be found impossible to make a bargain resting upon equity, for the sale of one's person, as the whole subject revolves in a circle of never-ending absurdities, justice leaving the parties where it found them: man with equal success having attempted to quadrate the circle, create perpetual motion, and make a contract for the sale of a man, by his own agreement, on consideration of value for value received by the slave upon the principles of slaveholding law! If a man could not perform the act of making himself a slave, how could another do it for him, or a state or a government without doing an act repugnant to that law of nature spoken of in the first article of your new Constitution? When, said Mr. S., I applied for these writs of Habeas Corpus some days since, to one branch of this court, it was remarked by one member of the court, that this case would require great consideration from its effect on the towns of this State, as it might subject said towns to the maintenance of worn-out, aged and infirm slaves, in the shape of paupers. That contingency is possible, said Mr. S., but forms no ground against awarding to the bondmen, that constitutional justice, so long withheld by the consent of these towns, as well as the avaricious masters. It was argued in the Somerset case by Mr. Dunning, the Counsel of the claimant of Somerset, that if this slave was set free by the judgment of the court, there were then at large fourteen thousand slaves in England, belonging to gentlemen in the West Indies, who, for their own convenience, had brought them to England, and valuing them at £50 per head, they would amount to £700,000, or $3,500,000. What was the memorable reply of Lord Mansfield? It was, "that a man's natural relations go with him everywhere, his municipal to the bounds of the country of his abode."And in answer to the suggestion of a loss by the proprietors of the 14,000 negro slaves in England, said Lord Mansfield, "we have no authority to regulate the conditions on which law shall operate. We cannot direct the law, the law must direct us." So, said Mr. STEWART, the argumentum ab inconvenienti should not apply in this case. If these slaves have been worn out by the consent of the public, if that public have folded their arms in silence, and witnessed the robbery of these men, from year to year, of their earnings (which might have supported them in the evening of life), it is right they should support them when they can toil no more in the enjoyment of their just liberty. For it is always dangerous for men to see liberty struck down in others, and because they do not taste its bitterness personally, passively to look on without resistance. It will sooner or later strike back on themselves. That man is not worthy of liberty, who will not fly to the rescue of his brother when he sees his freedom struck down or assailed. Our liberties are always invaded when the humblest individual is deprived of his, without our making all the resistance within our power. At the time of the argument of the Somerset case in 1771, the world was full of slavery, especially the West Indies, and the colonies of this continent—it was tolerated in all. But behold what may be done by the indomitable perseverance of one man, if that man be Granville Sharpe. He was a gentleman of small means, but of a great heart, and had for some time made the study of human rights a subject of great consideration. He had read, thought, and written in their behalf, and was the prosecutor who interested himself for Somerset, the slave of one William Stuart, a West India planter, and prepared much of the brief of Mr. Hargrave, and obtained the writ of Habeas Corpus, returnable in the court of King's Bench, at his own expense. The court heard the argument patiently the live-long day, and decided against the slave, on the authority of a case in 1749, in Lord Hardwick's and Lord Talbot's time. Nothing discouraged Granville Sharpe; at the next term he brought up Somerset a second time, and the question was so important, the court heard the argument a second time, and decided as before against the slave. Poor Granville Sharpe still contended that a slave "could not breathe in England," and having spent months in deep study, upon the law of England, though a layman, he brought up Somerset for the third time before the court of King's Bench which had Lord Mansfield for its chief, who did not meet poor Sharpe and his counsel with a rebuke for his unconquerable fanaticism and obstinacy, nor did the court throw down the common impediment to the march of mind and further consideration, by saying "res adjudicata," "res adjudicata!" No! where human liberty was concerned, or the great rights of self-ownership staked upon human reasoning and judicial determination, Lord Mansfield was not in haste to say "we have decided against human nature." The cause was argued a third time for a day in Westminster Hall, and Granville Sharpe had, since the last argument, descended into the deepest wells of English liberty and brought up a draught of the waters of life, liberty, mercy, and law, so pure, that when it was commended to the lips of the judges, they were made wise, the scales fell from their eyes, and they saw in its length and breadth the mighty truth beaming on the forehead of justice herself,—"that slaves cannot breathe in England," and the light of that day has shone on with increasing strength and beauty, until we can now say, that the sun which never sets upon tho realms of the British Empire, beholds in his circuit through the heavens, no slave to crouch beneath her vast illimitable power. But oh! what shall we say of the sublime humanity of Lord Mansfield and his compeers, who were not afraid to confess they had been wrong, and had the magnanimity to say it before a slaveholding age? This day saw the longest stride which British greatness ever took on the highway of human glory. Would to Heaven, said Mr. S., that all courts might imitate the illustrious example in administering justice in the sublime humility, which dignified the court and exalted our kind, as in the case of Somerset. The great principles established in the Somerset case awakened the philanthropy of England, and put forth its strength in 1783, '88. '92, '96, '97, and finally, in 1806, was successful in the abolition of the African slave trade by Parliament. Wilberforce, Pitt, and Fox [had previously been] foiled again and again, in Parliament, the theatre of their eloquence, and seat of their power, but justice finally prevailed. This was the first great blow struck for the man of Africa, in three hundred years from the beginning of his American and West Indian enslavement. But from that day, the vindication of his rights has been onward. Congress, in 1774, recommended the ceasing of the African slave-trade in December, 1775, but it was not abolished until Jan., 1808, by a law passed the March before, in 1807. Three acts of Congress were passed in 1814, 1820, and in 1824, increasing the penalties against transgressors, until it finally declared all who were engaged therein, were pirates, and subject to the pirate's doom [death]. An act of Congress passed in 1787, declared involuntary servitude, or slavery, should never exist in the North Western Territory, comprising the present States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and the Territories of Wisconsin and Iowa. These early acts of national legislation show which way the mind of the nation pointed at this time. [Details and context]. A slave is a rational human being, endowed with volition and understanding, like the rest of mankind, and whatever he lawfully acquires and gains possession of, by find ing or otherwise, is the acquirement and possession of his master.—4 Dessaus., 266. 1 Stewart Rep., 320—s. p. A slave connot contract matrimony; their earnings and their children belong to the master.—Slave-Law. Indians are held as slaves in New Jersey.—Halstead'sRep., 374. Behold the shameful injustice of the Law of Slavery. If it be found by a jury on inspection, that the person claimed to be a slave is white, the claimant must prove him a slave or he will go free; but if the jury find the person to be of African descent, the law of slavery presumes the person a slave, by whomsoever he may be claimed, and the burden is thrown on the alleged slave to prove a negative, that he is not a slave.—Wheeler's Law of Slavery, 22. The owner of a female slave may give her to one person, and the children she may thereafter have to another!—Law of Slavery, 2. A slave cannot be a witness before any Court or Jury against a free white in the land for the greatest injustice. This is one of its most horrible features. Look, said Mr. S., to the case of an alien-white-child. Suppose her to be the daughter of parents of the lowest class of those who migrate from Ireland to America, and that these parents should die on their passage over the Atlantic, leaving to the mercy of New Jersey Laws, and the good people of Perth Amboy, their daughter, twelve years old, who cannot read or write, barefooted, destitute and friendless. Under your laws, the Overseers of the poor bind her out, to the Mayor of Trenton; she has lived with this rich, popular and influential citizen but one little month; when by violence she is dishonored, by her master, the Mayor. Is he safe from the retributions of justice? Is she deprived of her oath [right to testify]? No. She comes friendless and lonely, and knocks at the door of your Grand-Jury-room. Humble and feeble as is that knock, it is quickly heard by the acuteness of humanity's ear. She enters the vestibule of the great temple of justice, and immediately the majesty of the entire law of the land, not only of New Jersey but of this vast Empire, stands in its mighty invisibility around for her protection, ready to be revealed in its power. She is invited, on oath, to tell the story of her wrongs, the indignant Grand-Jurors listen and believe, and find a bill against the Mayor; she goes and comes under the law's broad shield. This haughty man is found by the officers of the law, is arrested by its power, and brought before a Court to plead to this indictment. He is tried; a second time, she, the friendless, comes and tells the tale of her dishonor; confiding justice, humanity, loving and honoring men believe her story; he is convicted and attempts to fly the power of the State and Union, which is by that child's oath already set in motion, and will prevail against money and mobs of rescue, all of these cannot save the big criminal from the vengeance of the law; to the Penitentiary, for ten long years, he must and does go; yes, the merciful majesty of the law shines gloriously on the head of the friendless foreigner. This is being born free and independent by the law of nature, under your Constitution. But not so of the poor injured slave, man or woman, native born though they be, however cruel or terrible the wrong inflicted on them, by their owner or other free man, the slave is not to be heard to tell his or her story, however true, before any human tribunal in the land against a free white person. Is this being free and independent by the law of nature? Is this possessing the safety and happiness described in the first Article of the New Constitution, which your organic law declares to be the portion of all, of woman born? Slavery imports perpetual obligation to serve another! Does that look like being free and independent? Slavery, said Mr. S., is so abhorrent to all justice and mercy, that all the intendments of law and justice are opposed to it; so that the legal writers of slave countries say that it can only exist by force of positive law. The lex scnpta must be its foundation, and that I think you no longer have. The lex scripta must be the source of all of its mischievous power, which one human being can exercise over another, by making a fellow-being his slave, his chattel. The foundation of slavery which sprang up in our colonies, had, as a general rule, nothing but the barbarous custom of a few inhuman planters, in its origin, which custom was one within legal memory, and ran not back to that unsurveyed point of antiquity, transcending all human memory, where its source was hidden in the night of byegone ages. It has not that common law authority for its support, which was supposed to be handed down from generation to generation, in the libraries of judges and lawyers, as copies, as some conjecture, of obsolete, worn-out and extinct statutes. As the soul survives the body, so it is supposed these customs called common law, are the souls or spirits of departed statutes, the tomb-stones and graves of which can no longer be found. Cineres perierunt. But their imperishable souls still remain to guide and direct us on the journey of life, and as far as they speak in the language of authority over this land, they forbid in trumpet-tongues, the existence of this vile institution of slavery. Institution of slavery! Institution of horse-stealing, institution of gambling and the institutions of highwaymen, sound equally sensible, to a just and philosophical thinker. But slavery is within the memory of men, so far as its advent to to New World is concerned. We track it from the middle passage to this hour, from its first unholy foot-print at Jamestown to the last ones made this day by those now held in New Jersey; and if the Court finds a well-grounded doubt as to the authority for this institution existing, which is trying to nestle down on our soil, and taking rank with your scientific, religious and agricultural institutions, then give humanity the advantage of that: doubt, and put it to death. As between strength and weakness, power and imbecility, if a strong doubt arise in the minds of the judges, the mercy of the law says, decide in favor of imbecility and weakness, "those who are ready to perish," let their blessing come upon you. Every intendment is in favor of natural rights, until the contrary doth most manifestly appear. If the new Constitution has seriously drawn in question the villainies and crimes of this complicated institution of wrong, then this Court, acting within the spirit and scope of American institutions, are bound to give the slave the benefit of that doubt and set him free. A solid idoubt should secure emancipation. But thanks to the freemen of New Jersey, the court is not obliged to look through clouds to see the clear sky of Liberty beyond, for its Constitution, in its first section, asserts in the strongest form of the English language, the explicit principles put forth in the Declaration of Independence, when our country was introduced into the family of nations, by which we declared the great self-evident truth to be, that all men were created free and equal, and possessed of certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, which is the proposition of the Constitution of New Jersey, expressed so distinctly, that cavil itself looks on in humble silence, and hangs his head in mute despair. For these great man-rights, said Mr. S., as I have said, there is no buyer, no seller, no market. They are a trust confided to man, by his Maker, in order to place him at the head of the created life, and give him dominion over it; and his rank he can never sell, lose, or forfeit, so as to take his station as property among the quadrupeds and animals. In the fall of Adam man never fell so low, as the slave-holder would have wished; for, according to the law of slavery, the poor slave in the disastrous fall of the first transgression "which brought death into the world, and with it all our woes," the slave fell out of his manhood into chattel-hood, and fell on till he lost his wife, his children, and in the amazing descent as he further fell, he lost all his property, and all he should thereafter acquire; and as he further fell, he himself became property, and brought not up on solid ground, until he could say to the neighing horse, on the one hand, "thou art, as property, my brother," and to the lowing ox, on the other, "thou art my equal, my peer." Such is the slaveholder's fall, but this is one of man's pit-falls, and not one of his Maker's. Said Mr. S., he had an argument, which the Court might regard as novel, which he wished to urge—that each and every branch of our government, state or national, were under a most solemn covenant with one of the great nations of the earth, to use our best endeavors to abolish slavery, in every part of our country; and we have been living under the weight of that solemn and disregarded undertaking for the last thirty years. Said Mr. S., I understand a treaty made by the treaty-making power to be the solemn and paramount law of this land [pursuant to Art. VI, Sect. 2], and if I am right in it construction, the duty is imposed upon our nation, as I may well urge it even upon the judiciary of this State, as a co-ordinate branch of the government, to employ all the power it constitutionally may possess by its decision, to fulfil this engagement of the nation. The article, said Mr. S. to which I refer, is the 10th article of the treaty of Ghent, of the 24th December, 1814, made by the United States of America on the one side, and his Britannic Majesty on the other. Lest there should be some attempt to cavil, and pretend this article of the treaty had reference to the African slave-trade, I may be allowed to say there is not one word in the treaty except in the 10th article, which touches or relates to the subject of slavery, and it is an engagment relating to slavery as to the traffic generally in the two countries, for each had abolished the African slave-trade under the most tremendous penalties long before 1814; therefore the treaty referred to slavery generally in the two countries. The words of the 10th section of the treaty of Ghent are as follows:

United States Laws, 1st vol., 699. This treaty, so long dishonored on our part, has been most faithfully respected and obeyed on the part of Great Britain, They immediately began to adopt means for the subversion of slavery as a system in the West Indies. To be sure the violence, disorder, and Lynch-law of the slaveholders of the West Indies defeated the kindness, and deferred the approaching justice of the English nation for some years. It was astonishing to see the impudence of the West India planters, threatening dimemberment of the empire, revolution, and treason, as often as the mother country originated a measure in any degree preparatory to emancipation. These contumacious slaveholders did all in their power to frighten England from her high purposes,

The Moravian, Baptist and Methodist ministers exposed themselves to great rage from the slaveholders in attempting, as Christian ministers and good subjects, to preach the Gospel to the slaves, and aid them in information in furthering the objects of the mother country. Baptist and Methodist meeting-houses or churches were torn down and burnt, and these blessed ministers were in constant peril of losing their lives, and were occasionally imprisoned and banished from their homes and families. In fact, everything, which is said against emancipation and abolitionists in Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina, was said in the British West-Indies thousands and thousands of times by the press, resolutions of public meetings, the Island Legislatures, and the voice of man, against emancipation and British abolitionists; but on the passage of the great Reform Bill of England in 1833, about 500,000 new law-makers or voters were added to the old Parliamentary constituency of England, and when this fresh stream of popular power flowed, it rose so high, that on the bosom of its flood it carried into the New Parliament men deeply sympathizing with the great principles of justice, and one of their first acts of legislation was to declare slavery abolished in the West Indies, paying £20,000,000 sterling to the slaveholders, and giving them, the masters, six years more of the service of the slaves, so that emancipation would not take place until the first of August, 1840. This apprenticeship-system, regulated by a most complicated law, with especial justices to stand between master and apprenticed proved, if possible, more bitter than slavery itself. Nothing could have been more unfortunate, or fraught with greater injustice to the colored people. The master's avarice and cruelty arose in proportion to the shortness of the time he could exercise his despotism. The special justices intended for the slave-apprentice's friend, eat sumptuous dinners with the planter, and decided controversies in his favor. The humanity of the government in the apprenticeship was entirely defeated by the greediness, cruelty, and avarice of masters. The horrid flogging, the treadmills, and other instruments of slaveholding vengeance and torture were in full play during the probationary state. The mother country had been overreached in paying twenty millions of pounds sterling to see the objects of their solicitude so shamefully treated. The mistake of the home government was in supposing it possible to engraft a system of apprenticeship, education, and a preparation for freedom, on the old tree of slavery, and in having confidence in those brutal, cruel, and avaricious slaveholders, who, with their twenty millions of pounds, and six years of labor, only hated the poor slave the more as his liberty advanced day by day in his chains. Finally in January or February, 1838, the minister wrote to the Governors of these Islands, requesting them in the coming spring and summer to convoke those insular legislatures and ask them forthwith to abolish the remaining two years of the apprenticeship system, if the islands wished for the future good will of the slaves, or in fact, the protection of the parent country in case of insurrection. This stringent measure brought the obstinate slaveholders to their senses. The West India Island Parliaments were convoked, and the final acts of emancipation passed, to take effect simultaneously on the 1st August, 1838, except the Island of Antigua, whose Parliament, with great good sense, abolished slavery and apprenticeship both, in 1834, in an island of 30,000 blacks, and 5,000 whites—six to one. Great kindness, love, education, and prosperity followed this island. However, the eventful first of August, 1838, at last came, and instead if blood and insurrection, as prophesied by the selfish and cowardly, the blacks throughout the British West Indies, to the number of 800,000 human beings, who had been slaves, met in the evening of the 31st of July, 1838, and there continued in a solemn and quiet manner until the moment of midnight came, when the bells of the churches of the British West Indies struck, and played from island to island, while cannons were roaring throughout the Great Antilles—they were the glorious peals of freedom, the joyful freedmen raising notes of thanksgiving and praise to Heaven from bended knees, falling with hysteric transports of wild and delirious joy, into each other's arms. No mortal tongue or pen can describe the overflowing ecstasies of these naked and scourged bondmen, now standing up as British freemen—slaves no more. They sung, they cried, they danced, and thus in wild and rapturous joy they passed the terrific bourne so long wished for by them—so long feared and dreaded by the guilty white man. But the first drop of the white man's blood has not yet been shed, by these deeply abused and emancipated people. Many thousands of these long-injured people are now proprietors of two, four, eight, ten, and fifteen acres of land. Their wives and children stay at home and cultivate and raise enough for the family's food and clothing; the father works, or some older sons, on some neighboring plantation,—the money he or they earn pays.for land:—his wife and children create subsistence from his own fields. Hundreds of schools, and many colored churches, have sprung up for the adults and colored children. Once the planters raised nothing but sugar, molasses, rum, and coffee, and bought all their provisions from abroad; now the laborers' families raise their provisions on the island. Less sugar, to be sure, is raised, but two-thirds of the sugar goes, as a money question, farther now than all did in slavery, as more than one-third, sometimes one half, was spent for provisions which are now raised at home. So they have gone on with remarkable prosperity, both master and freedmen. The plantations have arisen, some twenty, thirty, and others forty and fifty, and many sixty and sixty-five per cent. above their slave value. In fact, the English government now feel that they acted unwisely in giving the twenty-millions of pounds, for the lands alone of those slave islands are now worth more than slaves and land both were in 1830. In fact, that is a matter of regret now, that the slave had not received what England had to give. On the same day, the fetters fell from the slaves of South Africa; from the Cape of Good Hope, six-hundred miles north, inland, the institution expired on the last acre of British supremacy—from ocean to ocean. On the 1st of April, 1844, England, through her East India Company's mighty powers, struck slavery dead through her Oriental Regions—twelve millions of slaves, serfs, and caste—crushed beings, lifted their unfettered hands to God to bless his power, and that of England's, which, amidst a population of one hundred millions of Eastern Indies, left them in chains to pine no more. Has not England most gloriously, in thirty years, from 1814 to 1844, performed her high and glorious undertaking with these United States in the treaty of Ghent? Has she not blotted out that great dishonor of our race from her vast dominions? What have we done to fulfil our part of this great national covenant! When the abolitionists presented from year to year, petitions clothed in dignified and respectful language, praying Congress to abolish the internal slave trade between the States, in the Territory of Florida, and in the District of Columbia, signed by tens of thousands of names, unread, undebated, unprinted, and unconsidered, they were laid upon the table. This being esteemed too great a privilege for humanity, during three years, these petitions, by a rule of the House of Representatives, were forbidden a reception by the House. The abolitionists, for endeavoring to fulfil the paramount law of the land, the 10th Article of the treaty, were defamed in Congress and out, their names cast out as fanatical and incendiary, they were mobbed by the countenance of men in high places, their churches destroyed, their halls burnt, and their people imprisoned and murdered! If slavery not only forbids and restrains a nation from performing its most solemn treaties, but violates them, and thus endangers the peace, prosperity, and happiness of the whole people, can it be doubted that it contravenes the 1st Article of your Constitution, which assures us that man has the right of "acquiring, possessing, and protecting property, and of pursuing, and of obtaining safety and happiness." Can safety, property and happiness be maintained by men or nations who violate faith, who are truce breakers? Is not that slavery which hazards the peace of a Nation by refusing obedience to the highest law of individual and national preservation, something tliat is contrary to the great law of nature? Every branch of our government—legislative, judicial or Executive—should have lent every encouragement and aid in their power to the removal of this cancer, battening with its roots in the jugulars of the Republic. But instead of Presidential and gubernatorial messages urging Congress and the State Legislatures, under this standing paramount treaty-law, to do all in their power within their respective jurisdictions to abolish slavery, slavery has mounted the highest places of power, and has rescinded and annulled the treaty, and compelled Presidents and Governors by messages and inaugurals to forewarn the Legislative Assemblies and the people to violate this treaty, and turn their entire power and legislative action against those who had petitioned for the abolition of slavery. Is not this high treason against the State and man's best interests? Has not slavery caused these high dignitaries to commit official perjury? And is not such a terrible institution hostile to man, his safety and happiness as a man and as a citizen, and is it not within the inhibition of the first section of your Constitution, and does it not violate that freedom and independence conferred upon him by the law of nature, and does it not stand between you and the enjoyment of the first article? What is that law of nature, by which all men are made free and independent? Allow me to define it as I understand it, said Mr. S. The law of nature is that great Omnipotent law of God, ever in full force amidst the busy hum of thousands in your emporium, or in the solitudes of the wilderness, on the sea, or on the land;

The law of nature is taken up and recognized by the good people of New Jersey, in the most solemn form as a rule of action, in her organic law. This first section declares that amongst man's unalienable rights are life, liberty, and the right of acquiring property. What, can a slave have safety, or acquire property? He who is nothing but a chattel, a piece of property himself, can he acquire safety? No; of all the innumerable murders committed by white men and women upon the slaves of the south (and there is no day goes by in which there is not more than one murder in each slave State, on an average), not a single white person has yet been executed for the murder of the colored man. The white is frequently hung in the slave States for stealing slaves, but not for killing them. Oh, sum of all human villanies, let the curse of God rest upon it, let every wind of Heaven be charged with its destruction, every rising sun be its destroyer, the rolling seasons its executioner!! Said Mr. S., slavery is the exact converse of every proposition contained in the first article of your new Constitution. Slavery throws down every human right in the market to the highest bidder. If slavery or semi-slavery, in the shape of children of slaves in this State continuing to be slaves, males until twenty-five, and females until twenty-one years of age, and this operation is to pass under the name of being born free, and persons forty-one years old and upwards to be retained as slaves for life, and slaveholders are to stand asserting their wicked power, then the first great section of your Constitution is converted into a vapid and senseless abstraction. Shall your Constitution be withered by the power of slavery? Shall this Constitution stand gilt with the gold of high pretension, while within it is full of ravening and dead men's bones? Shall this slave institution continue to exist in hostility to so plain a provision? This frightful institution claims to exist by the apology of some since the 2d of last September [1844], even since this Constitution went into operation, without a platform on which to place its accursed feet. Said Mr. S., the best foundation I can see for slavery in this State, at this time, and the length of time it should continue, should be the amount of time it would take the people of this State to recover from their astonishment at its inexpressible impudence. The institution of slavery is the converse proposition of the Ten Commandments, the essence of injustice and meanness in its most compact form; and it would seem that no nation not struck down by a mortal paralysis, would wait a moment before rising and striking down the monster, the first instant they discovered his seven heads and ten horns emerging from the forlorn regions of "Eldest Hell" [Ed. Note: Rev. 17:3-8 allusion]. Said Mr. S., which shall stand—the great written, organic law of liberty, or the unwritten and inexpressible villany of slavery? Which shall stand—the natural God-inherited rights of life, liberty, property, safety and happiness for each human being in New Jersey, or that of an institution which subverts every object for which a good Constitution was ever made? A Constitution ex vi termini imports a covenant made by the whole people, with each person, and each person with the whole people, to protect and defend their God-inherited rights of life, liberty, property and safety from violence and invasion. A Constitution is made for the defence of human rights and not for the destruction; a Constitution is the highest evidence of man's weakness; and to combine society's strength, for the defence of each individual. How is it possible that a Constitution, whether of this State, or of the United States, which were created on purpose for the protection of life, liberty, property and Safety, can exist and be entitled to the name, without overthrowing every institution villany or stratagem created or made, intending to cheat man out of life, liberty, property, safety and happiness? The men who framed the old State Constitution of New Jersey in the year 1776 were not such hypocrites as to stamp that Constitution with the protection of human rights. No, they said nothing on that subject, for they knew there were no inconsiderable class of the population of this State, who were wedded to the insatiable desire of appropriating the labor of others, without compensation, by compelling negroes, mulattoes, mestees and Indians, to work for them for nothing, and make chattels or property of their persons, their wives and children,—yes, of those human sinews as a marketable commodity, men were to be degraded and forbidden, under penalties of thirty-nine lashes, from wandering from their masters' homes on Sunday, for the infliction of which stripes, by the order of a justice of the peace, a constable did and yet does receive from the master the sum of $1 for performing the brutish service. To add to all other ignoble acts on the part of the State, was a provision forbidding emancipation of the slave, if forty years old or more, for fear of the distant contingency, that this freedman might become a public burthen to the township, by being a pauper in his old age, and rather than subject the towns to that, they preferred to let the man and his posterity remain in slavery. Such was the gross inhumanity of the age; thus cheap were human rights held by the people of this State at large. Gross inhumanity to the master himself; it took away his locus penitentiæ, his space of repentance [Ed. Note: Revelation 2:21 allusion]. And if slavery is not abolished, this infamous provision is still in full force. The reason, said Mr. S., why slavery was not abolished by name in Massachusetts and New Jersey is to be found in this, that the conscious shame of the fact restrained the framers of those Constitutions from immortalising their own disgrace by admitting slavery's previous existence, in and by its distinct abolition. They therefore put it to death by suffocation by the hands of liberty, without a name, hoping the judiciaries would attend its funeral and burial, and for ever remove its unsightly corpse from the sight and smell of men with as little parade as possible; and further hoping a generous posterity would disbelieve their early public history, and consider it as apocryphal and slanderous of their illustrious ancestors, as the Constitutions of these States do not so much as name so great a moral blemish on their historical fame.

Said Mr. S., by the statute of this State (which he contended was repealed by the 1st section of the new Constitution) passed February, 1820, all children born of slaves after 1804 were to be free, but belong as servants, and be held as apprentices, who are bound out by the overseers of the poor to the owners of their mothers, their administrators, executors and assigns, males till 25, and females until 21. These persons were property in every sense of the word, until their time expired; they are purchased and sold in private and at public auction, pass under the insolvent acts and bankrupt acts, the same as oxen and horses. What is the difference between this Mary Tebout and her mother? Nothing, until Mary has passed 21 years of unrewarded toil. She is called a servant, she is said to be born free, now but 19, and has been sold three times. The Southern States call slavery involuntary servitude, or persons bound to service by the laws of the States. The domestic institutions of the South, the patriarchial institutions and the peculiar institutions of the South—by such soft hypocritical use of words, do they mean to make the English language a partner in their guilt, by using it as a cloak to conceal the hideous visage of that frightful monster, whose mouth is filled with spikes, and cover her face with iron wrinkles, with burning balls of fire for eyes, whose every hair is a hissing serpent, whose fetid breath would kill the Bahon Upas, whose touch is ruin, whose embrace is destruction, who is fed on blood, tears and sweat, whip-extracted, from unpaid toil—her music is unpitied groans of broken hearts, of ruined hopes, and blasted expectations. Away, said Mr. S., with such artifice to shield deformity, by those cruel and wicked States, boasting of their republicanism, and rights of man. Even New York and Pennsylvania once held persons born free, whose mothers were slaves, the males till 28, and females till 25, as slaves. Terrible nick-naming of human rights, as in bold derision of them. These New Jersey servants are property, in its base sense, slaves for years, the parents deprived of all jurisdiction of their offspring, all direction of their education, and paternal tenderness; the law confining these poor servants, and obliging them to live with those who have owned and abused the mother who bore them, and are still continuing to hold their parents until death as slaves. The master can sell this servant and horse together. This servant-woman at 15, and the male-servant at 18, contract marriage, and when the woman is 19, and man 22 years of age, having three little children, the father is sold to one end of the State, and the mother to the other; their little children left in the street, the marriage relation broken, the paternal and maternal relation dissolved; these little ones not to see their parents for two years or more; the husband cannot see his wife or little ones, nor the wife her husband or babies for two years to come. Call you this being born free? The man is deprived of his wife, and the wife becomes a widow, and children orphans, according to law, to satisfy the claims of certain old slaveholders in this State! Is this being born free? This sort of being born free, "is keeping the word of promise to the ear to break it to the hope." This looks none like respect for the law of nature, by which we are born free and independent. We can never honor or respect the new Constitution, till we feel there is meaning, power, vitality, in those blessed words of justice, truth, mercy, freedom, safety; and further, feel that there are no birth-impediments, or interest of others in the use of our bodies, inconsistent with our own happiness. Each individual should be left to fulfil the object of his mission to this world in the best way he may; society should not load him with burdens for the benefit of others, but should give him every facility to run his race of existence, with dignity to himself, and thus truly serve the ends of society and his own creation, in passing from the great eternity of the past into the illimitable future. Here, Mr. S. said, we are not left in the dark as to the meaning of the words of the New Jersey new Constitution, for it is almost an exact copy of the first section of the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. Here Mr. S. read the first section of the Massachusetts Constitution in these words.