This site reprints the 1853 book, The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896). This site reprints the 1853 book, The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896).

Before the 1861-1865 War, a number of Christian abolitionists (Rev. Cheever, Fee, Weld, Rankin, Foster, Goodell, Pillsbury, etc.) opposed slavery. Nowadays, their Bible-based reasons for doing so are generally unknown. This series of websites educates by making the text of some of those writings accessible. Whether or not you agree with their position, it is at least a good idea to know what their views were! and not be relying on merely what century-later revisionists claim those views were. “It is not enough to know the past. It is necessary to understand it.”—Paul Claudel (1868-1955). For more, see www.iath.virginia.edu/utc/uncletom/key/keyII14t.html. |

The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin

Presenting The Original Facts

And Documents Upon

Which The Story Is Founded,

Together With Corroborative Statements

Verifying The Truth Of The Work,

by Harriet Beecher Stowe

(Boston: John P. Jewett & Co,

Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor & Worthington,

and

London: Low and Co, 1853)

This site presents a book by one of the activists, Harriet Beecher Stowe, from the period before the War (1861-1865).

This site presents a book by one of the activists, Harriet Beecher Stowe, from the period before the War (1861-1865).

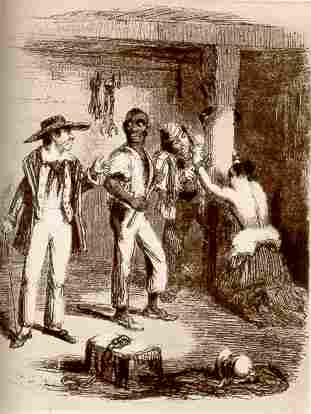

Mrs. Stowe had seen slaves' desperate efforts to escape the savagery of American slavery. She wrote in short story form, a number of narratives, to describe some of those abuses. Her 44 separate writings, short stories, were published on different occasions, each one time only, in a newspaper, over 44 different issues, as per the publishing style of that era. But public demand for reprints, led to them being later consolidated, collected together from being 44 separate out-of-print newspaper columns, into one more-convenient and accessible volume, collectively gathered under one title, as Uncle Tom's Cabin. Some Southerners accused her of misrepresenting slavery, exaggerating its savagery. She responded to critiocisms of Uncle Tom's Cabin by putting together the documentation, the documentation that composes this scholarly researched treatise on the subject, being reprinted here. She cites the accusations, then gives her responses, chapter by chapter. (Currently only the Preface, Part II's Chap. 12 (Roman law) and 14 (Hebrew law), and Part IV's Chapters 5 - 6 (New Testament teaching) and Appendix (1840 Census data), are available in full here.) Note her citing official Southern court precedents on slaver crimes including torture-murders, some still available at law libraries, e.g., the Mann case, the Souther case, the Castleman case, etc. The book is available with two different page numbering systems, one 259 page version with double-columns and one 508-page version with single columns. The site is in process of providing both sets of numbering, for your use, depending on which version you have. |

—•—

| Preface | iii |

| I. — Introduction | 5 |

| II. — HALEY: Author's experience. — Trader's letter.— Kephart's examination. —Invoice of human beings. — Various classes of traders. | 5 |

| III. — MR. AND MRS. SHELBY: Account of a well-regulated plantation.—Extract from Ingraham. | _ |

| IV. — GEORGE HARRIS: Advertisements. — Lewis Clark. — Mrs. Banton. — Story of Lewis' sister.—Mr. Nelson's story.— Frederick Douglas.—Josiah Henson's account of the sale of his mother and her children. —Recent incident in Boston. — Advertisements for dead or alive. | _ |

| V. — ELIZA: Author's experience. — History of a slave-girl and her escape. | 21 |

| VI. — UNCLE TOM: Similar case. — Old Virginia family servant. — Bishop Meade's remarks. —Judge Upshur's servant. —Instance in Brunswick, Me. — History of Josiah Henson. — Uncle Tom's vision. — Similar facts. — Story of a Boston lady. — Instance of the Southern lady on a plantation. — Story of an African woman. —Account of old Jacob. | 23 |

| VII — MRS. OPHELIA: Prejudice of color —Instance in a benevolent lady. — Dr. Pennington. —Influence of this upon slave-holders. — True Christian socialism. — Amos Lawrence. | _ |

| VIII. — MARIE ST. CLARE: The Northern Marie St. Clare.—The Southern Marie St. Clare.—Degrading punishment of females. — Dr. Howe's account. | _ |

| IX. — ST. CLARE: Alfred and Augustine St. Clare representatives of two classes of men. —Letter of Patrick Henry. — Southern men reproving Northern men.—Mr. Mitchell, of Tennessee. —John Randolph of Roanoke, — Instance of a sceptic made by the Biblical defence of slavery.—Baltimore Sun on Biblical defence of slavery.—Specimen of pro-slavery preaching. | 35 |

| X. — LEGREE: No test of character required in a master. — Mr. Dickey's account in "Slavery as It Is."—"Working up slaves"—Extracts from Mr. Weld's book. — Agricultural society's testimony. — James Q. Birney's testimony.—Henry Clay's testimony.— Samuel Blackwell's. — Dr. Demming's. — Dr. Channing's. — Rev. Mr. Barrows'. — Rev. C. C. Jones'. — Causes of severe labor on sugar plantations. —Professor Ingraham's testimony. — Periodical pressure of labor in the cotton season. —Letter of a cotton-driver, published In the Fairfield Herald.—Testimony as to slave-dwellings.—Mr. Stephen E. Maltby.—Mr. George Avery.—William Ladd, Esq.—Rev. Joseph M. Badd, Esq. —Mr. George W. Westgate. — Rev. C. C. Jones. — Extract from recent letter from a friend travelling in the South.—Extracts with relation to the food of the slaves. — Professor Ingraham's anecdotes. | _ |

| XI. — SELECT INCIDENTS OF LAWFUL TRADE. Separation of an aged mother from her son authenticated. — Selling of the woman to the trader authenticated. — Parting the infant from the mother verified. — Suicide of slaves from grief authenticated.—Parting of "John aged 30" from his wife authenticated. — Case of old Prue in New Orleans authenticated.—Story of the mulatto woman authenticated. | 47 |

| XII. — TOPSY: Effect of the principle of caste upon children. — Letter from Dr. Pennington.—Instance of the Southern lady. — Story of the devoted slave. | _ |

| XIII. — THE QUAKERS: Trial of Garret and Hunn.—Imprisonment of Richard Dillingham. —Poetry of Whittier. | _ |

| XIV. — SPIRIT OF ST. CLARE: Containing various testimony from Southern papers and men in favor of Uncle Tom's Cabin. | _ |

| I. — INTRODUCTION: Accusations of the New York Courier and Enquirer — Extract from a letter from a gentleman in Richmond, Va., containing various criticisms on slave-law. — Writer's examination and general conclusions. | 67 |

| II. — WHAT IS SLAVERY? Definitions from civil code of Louisiana. — From laws of South Carolina.—Decision of Judge Ruffin. —Involve absolute despotism. —Do not admit of humane decisions. —Designed only for the security of the mailer, with no regard for the welfare of the slave. —Judge Ruffin. —No redress for personal injury that does not produce loss of service. — Case of Cornfute v. Dale. — Decision with regard to patrols.—Decisions of North and South Carolina with respect to the assault and battery of slaves. — Decision in Louisiana, by which, if a person injures a slave, he may, by paying a certain price, become his owner.—Decision in Louisiana, Berard v. Berard, establishing the principle that by no mode of suit, direct or indirect, can a slave obtain redress for ill-treatment. — Case of Jennings v. Fundeburg. — Action for killing negroes. — Also Richardson v. Dukes for the same. — Recognition of the fact that many persons, by withholding from slaves proper food and raiment, cause them to commit crimes for which they are executed. — Is the negro a person in any sense? — Judge Clark's argument to prove that he is a human being. —Decision that a woman may be given to one person, and her unborn children to another. — Disproportioned punishment of the slave compared with the master. — Case of State v. Mann, showing that the owner or hirer of a slave cannot be punished for inflicting cruel, unwarrantable and disproportioned punishments. — Judge Ruffin's speech. | 70 |

| III. — SOUTHER v. THE COMMONWEALTH. THE NE PLUS ULTRA OF LEGAL HUMANITY: Writer's attention called to this case by Courier and Enquirer. — Case presented. — Writer's remarks. — Principles established in this case. | 79 |

| IV. — PROTECTIVE STATUTES: Apprentices protected. — Outlawry. — Melodrama of Prue in the swamp. —Harry the carpenter, a romance of real life. | 83 |

| V. — PROTECTIVE ACTS OF SOUTH CAROLINA AND LOUISIANA. — THE IRON COLLAR OF LOUSIANA AND NORTH CAROLINA. | 87 |

| VI. — PROTECTIVE ACTS WITH REGARD TO FOOD AND RAIMENT, LABOR, ETC.: Illustrative drama of Tom v. Legree, under the law of South Carolina. — Separation of parent and child. | _ |

| VII. — THE EXECUTION OF JUSTICE: State v. Eliza Rowand.—The "Ægis of protection" to the slave's life. | 92 |

| VIII. — THE GOOD OLD TIMES. | _ |

| IX. — MODERATE CORRECTION AND ACCIDENTAL DEATH.—STATE v. CASTLEMAN. | _ |

| X. — PRINCIPLES ESTABLISHED. — STATE v. LEGREE; A CASE NOT IN THE BOOKS. | 103 |

| XI. — THE TRIUMPH OF JUSTICE OVER LAW. | _ |

| XII. — A COMPARISON OF THE ROMAN LAW OF SLAVERY WITH THE AMERICAN. | 107 |

| XIII. — THE MEN BETTER THAN THEIR LAWS. | 110 |

| XIV. - THE HEBREW SLAVE-LAW COMPARED WITH THE AMERICAN SLAVE-LAW. | 115/223 |

| XV. — SLAVERY IS DESPOTISM. | 120 |

| I. — DOES PUBLIC OPINION PROTECT THE SLAVE? | 124 |

| II. — PUBLIC OPINION FORMED BY EDUCATION: Early training. — "The spirit of the press." | 129 |

| III. — SEPARATION OF FAMILIES. | 133 |

| IV. — THE SLAVE TRADE: What sustains slavery?—The FACTS again, and the comments of Southern men. —The poetry of the slave-trade. | 143 |

| V. — SELECT INCIDENTS OF LAWFUL TRADE; OR, FACTS STRANGER THAN FICTION: What "domestic sensibilities" Violet and George had. — Testimony of a sea-captain, and of a fugitive slave. | 151 |

| VI. — THE EDMONDSON FAMILY: Old Milly and her household. — Liberty and equality. — The schooner Pearl. — An American slave-ship.—Capture of fugitives. —Indignation. — Captives Imprisoned. —Voyage to New Orleans and return. — Affecting incidents. — Final redemption. | 155 |

| VII. — EMILY RUSSELL: Price of her redemption.—Not raised.—Sent to the South. — Redeemed by death. — Daniel Bell and family. — Poor Tom Ducket. — Facsimile of his letter. | _ |

| VIII. —KIDNAPPING: Causes which lead to kidnapping free negroes and whites.—Solomon Northrop kidnapped. — Carried to Red river.—Parallel to Uncle Tom.— Rachel Parker and sister. | 173 |

| IX. — SLAVES AS THEY ARE, ON TESTIMONY OF OWNERS: Color and complexion. — Scars. — Intelligence. — Sale of those claiming to be free.—Illustrated by advertisements. — Inferences. | 175 |

| X.—POOR WHITE TRASH: Slavery degrades the poor whites. — Causes and process. — Materials for mobs. — Fierce for slavery. — Influence of slavery on education. — Emigration from slave states.—N. B. Watson advertised for a hunt.—John Cornutt lynched.—No defence in law.—Justice prostrate.—Rev. E. Matthews lynched. — Case of Jesse McBride. | 184 |

| I. — INFLUENCE OF THE AMERICAN CHURCH ON SLAVERY: Power of the clergy. — The church, what? — Influence.—Points Self-evident.—Course of ecclesiastical bodies.—Sanction of American slavery, as it is, by Southern bodies. — Summary of results. | 193 |

| II. — AMERICAN CHURCH AND SLAVERY: Trials for heresy. — Course as to slavery heresies. — Course of the Methodist Church.— Course of the Presbyterian Church, before the division.—Course of the Old School body. — Course of the New School body. — Results. — Congregationalists. — Albany convention. —Home Missionary Society. —The protesting power.—Practical workings of the general system.—Pleas for inaction.— Appeal to the church. | 205 |

| III. — MARTYRDOMS: Power of Leviathan. — He cares more for deeds than words. — E. P. Lovejoy at St. Louis. — At Alton. — Convention. — Speech. — Mob. — Death. | 223 |

| IV. — SERVITUDE IN THE PRIMITIVE CHURCH COMPARED WITH AMERICAN SLAVERY: Fundamental principles of the kingdom of Christ. — Relations to Slavery. —Apostolic directions. — Case of Onesimus. | 228 |

| V. — TEACHINGS AND CONDITION OF THE APOSTLES: Apostles and primitive Christians not law-makers. — Preaching of modern Law-makers. | 234 |

| VI. — APOSTOLIC TEACHING ON EMANCIPATION. | 235 |

| VII. — ABOLITION OF SLAVERY BY CHRISTIANITY: State of Society. — Course of councils. — Influence of bishops for freedom. — Redemption of captives.—Contrast. | 237 |

| VIII. — JUSTICE AND EQUITY VERSUS SLAVERY: Regulation of slavery impossible.— Contrast of its principles and provisions with justice and equity. | 241 |

| IX. — IS THE SYSTEM OF RELIGION WHICH IS TAUGHT THE SLAVE THE GOSPEL? Points to be conceded.—What is taught?—Principles and discussion.—Necessary results of the system. — Specimens of teaching and criticisms. | 244 |

| X. — WHAT IS TO BE DONE? Work of the church in America.—Feelings of Christians in all other countries. — Eradication of caste, and repeal of sinful laws against free colored people.—Various duties and measures as to slavery. — Closing appeal. | 250 |

| APPENDIX. — Statistics Abused — Falsified 1840 Census. | 257 |

The undersigned having an excellent

The undersigned having an excellent