This site is one in a series on the abolitionists from before the 1861-1865 Civil War.

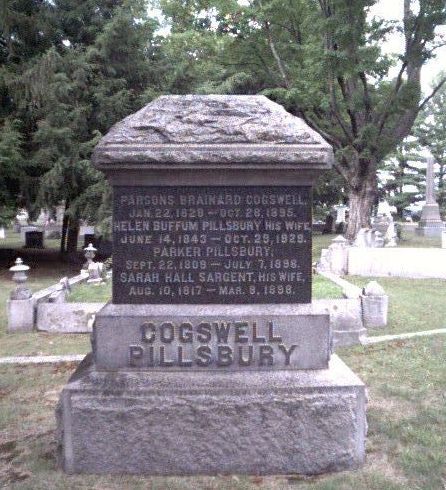

This site presents a book by one of them, Rev. Parker Pillsbury (1809-1898).

This site is one in a series on the abolitionists from before the 1861-1865 Civil War.

This site presents a book by one of them, Rev. Parker Pillsbury (1809-1898).

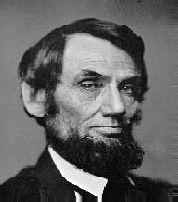

Abolitionists such as Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) had shown slavery to be a sin. But many, even "most," clergymen were evil, pro-slavery. By the time Pillsbury wrote this book, in 1883, many Americans had forgotten the events leading to that war; pro-South disinformation was being circulated instead. This was in two contradictory styles: Telling two different stories at the same time is classic fraud. Both stories cannot be true! But both stories may be false, as in this situation. The real truth was, Evil clergy had even supported U.S. wars of conquest, e.g., stealing Texas from Mexico, in a war of aggression, pp 81 and 381. This is not to mention other Southern evils cited by other abolitionists, and later killing hundreds of thousands of people. Pillsbury had excommunicated the vile clergy, p 374, the vast majority in the U.S.A. He, and real Christians (Protestant and Catholic, as shown in this series), had fought slavery. The real Christians, not the pretenders, were now, 1883, being forgotten. As in the book Nineteen Eighty-Four [1984] by George Orwell, the truth of history was being rewritten, falsified. The facts of the time were being reversed, to state the opposite of what had happened, to conceal the facts of the majority clergy's wicked record from their gullible members / sheeple. (This type lying continues to present!) Harriet Martineau (1802-1876), in Society in America (1837), § XVI, "Administration of Religion," had warned that once slavery was abolished, clergy might try to steal the credit: "if the clergy of America follow the example of other rearguards of society, they will be the first to glory in the reformation which they have done their utmost to retard." Now, decades later, this predicted credit-stealing was occurring. “After the war, former Confederates [had] wondered how to hold on to their . . . pride after [the] devastating defeat. . . . So they reverse-engineered a cause worthy of [their] heroics. They also sensed . . . that the end of slavery would confer a gloss of nobility, and bragging rights, on the North," says Donald von Drehle, "The Civil War, 1861-2011, The Way We Weren't" (Time, 18 April 2011), p 40. So pro-slavers, unreconstructed Confederates, and their apologists and accessories resolved on denial and disinformation, including pretending that the pro-slavery clergy had helped end slavery!!! “The readiness with which Southern [slavers and defenders] prefer the most false and audacious claims . . . exhibits a state of society in which truth and honor are but little respected,” says Lewis Tappan, Address to the Non-slaveholders of the South: on The Social and Political Evils of Slavery (New York: S.W. Benedict, 1843), p 36. Of course they'd lie! and keep on doing so! both before and after the Civil War. So Pillsbury, by then (1883) age 73, wrote this history to set the record straight in abolitionists' honor, and to remind Americans of the fakes, the pretenders, whom he had excommunicated, p 374. The real truth was: "[N]othing . . . has done so much to tolerate and perpetuate the sin in our midst, as the practice [tradition] of the Church."—Rev. John G. Fee (1816-1901), Anti-Slavery Manual (1851), p 69. See parody, pp 326-327. Accordingly, President Abraham Lincoln gave no credit for ending slavery to the churches, but instead, quite the opposite, had credited the anti-clerical William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) and others: "The logic and moral power of Garrison and the Anti-slavery people . . . And the army have done it all," freed the slaves, cited by Truman Nelson (History Writer), Documents of Upheaval: Selections from William Lloyd Garrison's THE LIBERATOR, 1831-1865 (NY: Hill and Wang, 1966), xvii Churches were creating pagans, infidels, by their bad examples and doctrines, said Rev. William W. Patton (1846). Such evils are a legacy of the various Roman Emperors, including Diocletian's persecution of the Early Church. U.S. slavery was unconstitutional. John Wesley called it the "the vilest." Such history is vital now, in 2009, as the fakes, the pretended Christians, continue. Some still say the Bible is FOR slavery; others pretend to have 'repented' of their predecessors having been pro-slavery! Both groups lie, pretend the bulk of U.S. clergy were anti-slavery! despite the truth having been the extreme opposite! Neither group (the deniers of slavery-being-a-sin, and the pretenders-of-having-opposed-slavery) bring forth "fruits meet for repentance [Luke 3:8]." They bring forth

To go to the "Table of Contents" immediately, click here. |

by Rev. Parker Pillsbury (Concord, N.H., 1883)

Some books, judged by their titles, are more remarkable for what they do not contain, than for what they do. This work is only Acts, not the Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles. It is only a small portion of a very small part of those apostles. There were many in the great west, as well as not a few in the east, whose labors, sacrifices and sufferings entitle them to volumes of well-written biography, who can scarcely be mentioned here, even by name. At this time of my life of nearly three score and fourteen years, more than forty of which have been spent in the field of moral, peaceful and religious agitation for the rights of humanity, it seemed presumption in me to attempt a labor of even this magnitude. And it was only earnest, continued importunity on the part of my very few surviving associates in the conflict, and their friends, that finally determined my course. Truth only has been sought. Not the whole truth; for that were impossible. But strict truth and exact justice, to the full extent of my time and space. The present generation knows little of the terrible mysteries and meanings of slavery or anti-slavery; the outrages and horrors of the former, or the desperate and deadly encounters with the monster by the latter, long before the cannonade of Fort Sumpter, or the dreadful war chorus of the subsequent rebellion. And all which is now attempted is some disclosure of those mysteries. By anti-slavery apostles are meant those only whose work was in the lecturing field; who literally "went everywhere preaching the word;" often as with their lives in their hands. Nor will only few of them, however worthy and deserving, be mentioned even by name. This work will be rather pictures and sketches than history. It will hardly enter more than two states, New Hampshire and Massachusetts; never go beyond New England. But in New England every type and phase of anti-slavery experience, doing, suffering and triumphing was represented to the fullest possible extent. What was true there was true everywhere in the country. And the truth on slavery and anti-slavery can be presented on so small space, and in time equally limited, as well as if the whole country were included, and all the thirty years of the moral and peaceful, and so, truly religious, agitation of the mighty problem were covered and all the heroes and martyrs named. The whole, as originally intended, would have comprised acts and experiences of some of those heroes, with brief personal sketches of them, together with short biographical notices of William Lloyd Garrison, of The Liberator and Nathaniel Peabody Rogers, of the Herald of Freedom. But, as the work of writing went on, articles began to appear from our old opponents or their children, not only declaring that they or their fathers abolished the evil, but that it could have been sooner and more easily done, "had Garrison and his small, but motley following" been out of their way! So some chapters of acts of the pro-slavery apostles, became necessary; at cost of both extending the volume, and also excluding some worthy names and noble deeds that had earned good right to grace these pages. These misrepresentations came mainly from the clergy, as did most of our bitterest opposition while prosecuting our anti-slavery labors, as will be hereafter shown beyond all question or contradiction. So now the order of the book will be:

And it scarcely need be added that the abundant testimony adduced, is only a small part of what the churches and their ministers have treasured up against themselves, to be hereafter unfolded from their own archives, should occasion for it ever arise.

Abolitionist Reunion - 1893 Danvers, Massachusetts Historical Society

-vii-

-viii- ACTS OF THE ANTI-SLAVERY APOSTLES. —•— WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON. The Acts of the twelve apostles are not the history of Christianity. Nor will the Acts of the Anti-Slavery Apostles be a history of the anti-slavery movement in the United States. My own beginning in that sublime enterprise was in the year 1840, when, dating from the establishment of The Liberator in Boston, by William Lloyd Garrison, it was about ten years old. At that time, so far as can be shown, was first announced the doctrine of immediate unconditional emancipation to every slave, without compensation to master or expatriation to the slave. Most of my anti-slavery work was of the missionary character, as was that of the first Christian apostles, who "went everywhere preaching the word." And the purpose of this Scripture is to present a true record, as far as practicable, of what passed under my own immediate observation, and in which it was my honor to bear some humble part. My earliest associates, editors as well as lecturers, are mostly now no more, and some personal account of a part of them is also in my present contemplation. My first anti-slavery newspapers were The Liberator, The Emancipator, published in New York, organ and property of the American Anti-Slavery Society, and Herald of Freedom of Concord. New Hampshire. Through some changes occurring in 1840, The Emancipator passed out of the society's hands, but was immediately succeeded by the National Anti-Slavery Standard, which continued with unswerving integrity till slavery was abolished in the country by presidential proclamation, and the male slave at least was made secure in his right of suffrage and citizenship. The first issue of his Liberator by Mr. Garrison was on January 1, 1831. It was a most humble, unpretentious little sheet of four pages, about fourteen inches by nine in size, but charged with the destiny of a race of human beings whose redemption from chattel, brutal bondage, was one day to shake to its foundations the mightiest republic ever yet existing on the globe.

The next day was Saturday, and I went by stage to Fitchburg, about fifty miles, and on Sunday evening delivered my first address on slavery, as agent of my association. And though I did in the course of that year, and the beginning of 1840, accept and occupy the position of a minister for a very small Congregational church and society in an obscure New Hampshire town, it seems on the whole more pertinent, proper and desirable, to date the beginning of my life mission and labor from that anti-slavery committee meeting in Boston and introduction to Mr. Garrison, and first work as an anti- slavery agent in Fitchburg and through the county of Worcester in the spring of 1839. Of the boyhood history of Mr. Garrison this may not be the place to speak. Like many men of high eminence, he commenced life among the lowly. Nor was his native town, Newburyport, Massachusetts ever distinguished for any but most conservative ideas in government, religion or social policy. His excellent mother, a devout member of the Baptist church, early sent him to learn the trade of a shoemaker. Fortunately too early, for his knees could not support the lap-stone, the anvil of the shoemaker of that day, and he was soon discharged, and entered as an apprentice to a cabinet maker. But neither was this a success. Nor did he even approach nor tend to his future high calling, until, while still a youth, he entered a printing office. That, as has been truly said, was to him high school, college and university, from which he graduated with honors, after long and faithful apprenticeship. His first business enterprise was to establish a little newspaper in his native town, which he characteristically named the Free Press. He soon learned, how ever, that the time for a Free Press was not yet. But the voice of his genius still said, Cry! and he responded next in Boston, with the National Philanthropist devoted doctrinally and practically to entire abstinence from all intoxicating drinks. His motto was, "Moderate drinking, the down-hill road to drunkenness." This undertaking was in the year 1827, when he was twenty-two years old. But the Philanthropist like the Free Press proved a premature birth. In 1828, his powers of mind and heart coming to be better appreciated, he had and accepted a proposition to go to Bennington, Vermont, and establish a political paper to be known as The Journal of the Times, and to advocate the claims of John Quincy Adams to the Presidency of the United States. Here, again, was a failure, and this journal soon slept with its predecessors. However, the valiant, persevering young editor was still full of courage and hope, and held on his way. He soon made acquaintance with Benjamin Lundy, an early, brave and true-hearted Quaker anti-slavery man, though hardly yet a pronounced abolitionist. Of kindred spirit, in the main, the two men formed a partnership in the autumn of 1829, and together published the Genius of Universal Emancipation. But though of one spirit, there was in methods between the two men a difference wide as earth and heaven. Mr. Lundy, in common with the highest humanities of the time, only demanded a gradual removal of slavery. Mr. Garrison, instead of gradual, almost stunned the nation with the new and more excellent evangel: "IMMEDIATE AND UNCONDITIONAL EMANCIPATION!" Here, then, was a new problem to be solved, or reconciled. An organized existence with one heart, but two voices: one serene, quiet, such as men might hear but not fear; the other the seven unloosed Apocalyptic thunders that men should hear, and hearing, tremble, as had Thomas Jefferson already, even in anticipation, almost half a century before the terrible utterance was heard by mortal ear! But Friend Lundy's persuasion prevailed for the present. After long, honest consideration and discussion, he finally said to Mr. Garrison: "Well, thee may put thy initials to thy editorial articles and I will put my initials to mine." But the stern logic of events soon showed that iron and clay could never be so welded together. This was in Baltimore, a slave-breeding, slave-trading, slave-holding city; indeed, had already become a great shipping emporium of the domestic slave trade of the United States! where, as has been said, slave pens flaunted their signs in open day on the principal streets, their rich owners the best city society and most devout worshippers in Christian churches. The wonder was that the gradualism of Lundy could be tolerated. And he soon learned who had struck at the great tap root of the deadly upas. Mr. Garrison wrote:

And so the Genius of Universal Emancipation would undoubtedly have soon been buried in the tomb of its three predecessors who owed their paternity to Mr. Garrison. But his intrepidity and fidelity in denouncing the domestic slave trade and exposure of its great cruelty, in the action of a ship captain engaged in it from his own native town of Newburyport, led to his arrest on a charge of libel, and conviction, fine, and imprisonment in a Baltimore jail. Nor had he one friend in the city to prevent it, if even to deplore his fate. Released from prison, his fine and court expenses being paid by Mr. Arthur Tappan of New York, and his partnership with Friend Lundy dissolved by mutual consent and in most cordial spirit, Mr. Garrison conceived the thought of establishing a paper at Washington, where the slave power and the domestic slave trade, in all their terrors, had established themselves under the sheltering wing and by direct authority of the Federal Government. Having in August, 1830, issued his prospectus, he visited the principal cities between Baltimore and Boston to test the tone of the public feeling for such an enterprise. But though he found Boston scarcely more friendly to his doctrines and determinations against slavery than even Baltimore itself, he finally concluded that it, rather, than Washington, was the ground whereon The Liberator should be set up. Writing, after his tour of observation, he said:

Thus, at last, had come the hour and the man. The great clock of the eternities struck the hour. And out of the dread silences came the prophetic word which was to finish the work of Washington and the Revolution, proclaiming "LIBERTY throughout all the land, to all the inhabitants thereof [Leviticus 25:10]." In a Baltimore prison he had learned to "remember them that are in bonds, as bound with them [Hebrews 13:3];" and this was his self-consecration, in the earnest strains of Thomas Pringle:

*The Liberator, Vol. 1, No. 1: Saturday, January 1, 1831. This was the man in his sixth and twentieth year. His work and word, if not his name, was The Liberator. And to the end this was his motto: "My country is the world; my countrymen are all mankind." Of the philosophy and method of Mr. Garrison as the acknowledged leader of the anti-slavery movement, a few words cannot here be out of place. In scripture phrase it might be sufficient to say, "the weapons of his warfare were not carnal." He was ever pre-eminently a man of peace. At this time he was a devout believer in the truest, best interpretation of the New Testament, especially of the Sermon on the Mount and the story of the Good Samaritan. He held his mission to be a completion of the work begun in the Revolutionary War; but in magnitude, sublimity and solemnity, as well as in probable results on the destiny of the world, as far transcending that, as moral truth and right transcend physical force. All war, he held to be inherently, intrinsically wrong. And so he early declared all carnal weapons, even for deliverance from bondage, contrary to the spirit of Christ as well as of His teachings; and even counselled the slaves earnestly against any resort to them in achieving their liberty. And the Constitution of the American Anti-Slavery Society, work of his hand, contained such a provision. In a "Declaration of Principles adopted by a convention assembled in Philadelphia to organize a national anti-slavery association," are words like these from the same brain, heart and hand:

After much more in similar strain, follows this:

In youth, Garrison had been a pronounced politician of the conservative party, as were most of the leading men of his native town. It was the sound of the Greek revolution against Turkish despotism which first filled his ear, and fired his young soul with the spirit of freedom. The powerful appeals of Daniel Weebster and Henry Clay in the American Senate fed the flame. Webster became to him the divinity of the forum. He even contemplated at one time a brief term at the West Point military school that he might take the field in person in the cause of the struggling Greeks. John Randolph had not yet told him and Webster and Clay that "the Greeks were at their own doors." But as Mr. Garrison increased in wisdom and spiritual stature, and it became evident that he was to be the divinely constituted leader in the sublimest movement in behalf of liberty and humanity of many generations, his vision was so anointed that he saw clearly that, though he was indeed to wrestle with principalities and powers, and with spiritual wickedness in high places also, his weapons were to be drawn from no earthly magazines. The sword of the spirit of Truth only, was to be made mighty in his hands, to an extent such as had not been beheld before, from the day when an apostate Christianity in the person of Constantine the Great, mounted the throne of the Cæsars and most ingloriously proclaimed herself mistress of the world! When the American Anti-Slavery Society was formed in Philadelphia, in 1833, Garrison was a New Testament Christian, as he understood the word, in all the word can rightly be made to mean. And most of all, did he reverence the doctrines of freedom and peace. Peace on earth, liberty and good-will to men, to all men, and all women, were then his proclamation and song. Human life he came to regard as sacred above all other things. And so capital punishment and war, as well as slavery, were to him an abhorrence. Hence, logically, he renounced all allegiance to human governments founded in military force, and openly proclaimed himself disciple of the Prince of Peace, in these memorable words:

The New England Non-Resistance Society was organized in 1838, and Mr. Garrison was elected corresponding secretary and member of the executive committee; and many of its first official papers and records, besides breathing his spirit, bear unmistakable imprint of his brain and hand. A portion of the preamble to its constitution reads thus:

A part of Article II of the constitution reads:

At this time it cannot be doubted that the belief of Mr. Garrison in both the inspiration and authority of the Bible, the Trinity and Atonement, but especially in all the teachings and precepts of Christ, was almost precisely such as was then, and still is professed, by the whole Evangelical church. Among his many devout poetical effusions this will be found:

Such was Mr. Garrison as a Christian, as a follower of the Christ of the New Testament. And wondrously consistent with his faith were his spirit, his life, and his whole character. At home or abroad; in private or in public; as writer or as speaker; as husband, father, friend, neighbor, or in whatever relation; after long, wide, and intimate acquaintance with men in pulpit, church, politics, and the world at large; for the constant exercise of what we call the Christian virtues and graces, I surely have seen few the peer, none the superior of William Lloyd Garrison. And yet he was called an infidel by almost all the universal church of the nation, from the university and theological seminary down to the humblest village pastors, churches, and Sunday-schools. With a life pure and spotless as the white plumage of angels, his whole character and conduct unsullied by the slightest breath of reproach, blessing many temporally and spiritually with whom he had intercourse, gentle and patient with ignorance, forbearing and long-suffering with prejudice and perverseness, and yet bold and brave, unconcealing and uncompromising where oppression and iniquity, injustice and cruelty were to be exposed and rebuked, no matter in what high places entrenched—yet was he branded, blasted as infidel, even atheist, when those words were made to stand for, were presumed to stand for all that is to be dreaded, shunned, execrated and exterminated at whatever cost! Revering the New Testament as law divine, he studied and respected its teachings. Did he read "Resist Not Evil?" He observed the sacred requirement, preached it in his journal, The Liberator, and practiced it everywhere. Hence arose the Non-Resistance Society, as well as a great national anti-slavery movement, which, without proscription, rested substantially and was largely sustained on a similar foundation. With him "love your enemies" never meant shoot them in war, nor hang nor imprison them in peace. And so The Liberator, which was his own property from first to last, was not only a proclamation of peace, liberty and love on earth, but of general, universal unfolding, progressing and perfecting to all man and womankind. But, joining himself to no religious sect nor party, chained down to no narrow, dogmatic ringbolt, he had ever eye and ear, as well as heart and hospitality, for whatever new truth might appear—in whatever book, science or religion it might be found. And what wonder if years of violent opposition and persecution from almost the whole American church and clergy on account of his fidelity to the Christian doctrines of peace, purity and liberty as they were taught in the sermon on the mount, and the unswerving example of its great Author, should have clarified and quickened his vision mentally and spiritually! At any rate, he subsequently re-examined the faiths and formulas of the professedly evangelical sects in religion, including their avowed belief in plenary inspiration of Holy Scripture. As one result of his farther investigations, he attended a convention at Hartford, Connecticut, in 1853, called especially to consider the claim and character of the Jewish and Christian Scriptures. The meeting was very large, having representatives, men and women, from east and west, continuing four days, with three long sessions each. In one of them Mr. Garrison offered and ably defended a series of resolutions, the first of which was to this purport:

And yet, to the end of life, no man more venerated or made wiser use of the Bible than did Mr. Garrison. A late testimonial of his reads thus:

Garrison early learned to doubt nothing only because it was new, and he accepted nothing unless he saw on it more than the mold and moss of age and time. He found the world, even its most enlightened people, dead in the trespasses and sins of intemperance, slavery, war, capital punishment, and woman's enslavement. He lived to set on foot, or largely and liberally co-operate in enterprises and instrumentalities for correcting all these abuses, for righting all these fearful wrongs. But at last there came another stranger to his door. With characteristic hospitality that door was again opened. Francis Jackson, one of the noblest, bravest, most steadfast supporters of Mr. Garrison and his life work, once said with respect to sheltering and protecting the fugitive slave: "When I unfeelingly shut my door against a hunted, fleeing slave, may the God of compassion close the door of his mercy against me!" So no slave, nor even stranger, ever appealed in vain to Garrison. The new guest was Spiritualism. That was a "sect everywhere spoken against" as fast as it grew in numbers—as anti-slavery had been in the generation preceding it. Even many of the best abolitionists, men and women who had bravely suffered persecution for and with the slave, treated it with contempt and scorn. Not so, never so, with Mr. Garrison. Many of his truest friends, some of them Quakers, as well as of other religious denominations, became early and devoted spiritualists, and that alone would have forever prevented him from dismissing, still less condemning, any stranger or defendant uncondemned, or even unheard. And in finally giving the new and mysterious idea recognition, he found, and to the end of his life believed, that he had literally entertained angels, and angels not unawares. Nor did he hesitate to make proclamation of the new and sublime Evangel. In The Liberator of March 3d, 1854, is an article from his pen, of which the following are but the opening paragraphs, giving a detailed account of a highly demonstrative seance he had just attended in New York, where writing, rapping, drumming, "drumming in admirable time and most spiritual manner," and other wondrous phenomena were witnessed. He wrote: We are often privately asked what we think of the "spiritual manifestations," so called, and whether we have had any opportunities to investigate them. have spread from house to house, from city to city, from one part of the country to the other, across the Atlantic into Europe, till now the civilized world is compelled to acknowledge their reality, however diverse in accounting for them; as these manifestations continue to increase in variety and power, so that all suspicion of trick or imposture becomes simply absurd and preposterous; and as every attempt to find a solution for them in some physical theory relating to electricity, the odic force, clairvoyance, and the like, has thus far proved abortive—it becomes every intelligent mind to enter into an investigation of them with candor and fairness, as opportunity may offer, and to bear such testimony in regard to them as the facts may warrant: no matter what ridicule it may excite on the part of the uninformed or sceptical. At the burial of his friend Henry C. Wright, who died on the 16th of August, 1870, he made one of the most eloquent and impressive addresses of his whole life. Mr. Wright had been for several years a pronounced and active spiritualist, and this is the tribute, or a portion of it, which Mr. Garrison paid to that part of his life work:

When spiritualism was on trial at the bar of the judgment of this world, some of Mr. Garrison's friends saw with deep regret his hospitality and charity towards it. There were those who even denied positively that he was, or was in any danger of becoming, a spiritualist. So doutbtless his early political and religious associates felt and reasoned, when they saw his heart warmed, and his hand and voice were lifted in behalf of the imbruted slave and his few devoted, but despised and persecuted friends. With his shining talents and deep devotion to his then sincerely cherished political and religious principles, both of respectable and popular character, how could he ever become an Abolitionist? But there's a Divinity that shapes our ends; and Garrison was a young man when he wrote:

And spiritualism he yoked to his chariot of salvation so soon as he espoused it in its fullness and conscious truth, as had already his friend Henry C. Wright, a few years before, and doubtless in the full faith and hope of Lord Brougham, when he wrote: "Even in the most cloudless skies of Skepticism, I see a rain-cloud, if it be no bigger than a man's hand, and its name is Spiritualism." NATHANIEL PEABODY ROGERS When some discerning Romans saw how many statues were reared in their city to persons of only indifferent merit, while Cato, one of their wisest and best, had none, they wondered. But the great man had answered the question beforehand: "Better that posterity should ask why Cato has not a monument, than why he has."

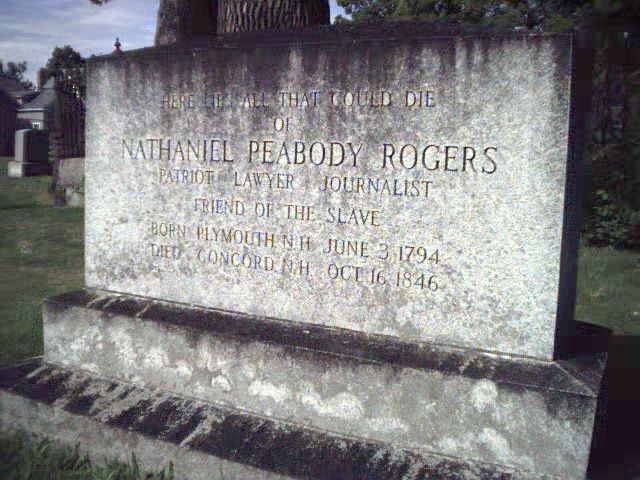

And yet to that hallowed spot I have conducted many devout pilgrims from east and west, both women and men. For there, since Sunday, the 18th day of October, 1846, exactly thirty-six years ago this very [1882] day, and almost hour, have slumbered the mortal remains of Nathaniel Peabody Rogers, surely one of the brightest, noblest, truest and every way most gifted sons, not only of the Granite state, but of any state of this union of states, departing at the early age of only fifty-two years. And no visitor from near or remote, ever fails to ask, sometimes with almost stunning emphasis: "Why has Rogers no monument?" Should that sacred spot speak out from its silence of six and thirty years, doubtless its answer to the eminently pertinent inquiry would be, as was that of Cato, so well remembered, so much admired, so often repeated now, after more than two thousand years. Such as was Rogers, never die. They need no monuments reared by other hands than their own. Time mows down all marble and granite, tramples out all inscriptions in bronze or brass. And so such registers are soon lost for evermore.

And scarcely of any man departed or still visible to mortal sight, could this be sung more appropriately than of the subject of this chapter {Nathaniel P. Rogers]; and for some seven years editor of the Herald of Freedom, published in Concord, New Hampshire, ten or twelve years.

And surely the blood of the martyr, literally and spiritually, flowed in the veins of his remote descendant, answering "heart to heart," as well as "face to face." For those who have been privileged to see both our departed editor in the flesh and form, and a singularly well preserved portrait of the martyr in the American Antiquarian Society hall at Worcester, Massachusetts, have wondered at the remarkable resemblance in the shape of head and face, in complexion, color of eye and hair, and the whole general expression of the two memorable men. He graduated with honors at Dartmouth college, in the year 1816. He studied law with the distinguished Richard Fletcher, and then settled down to its practice in his native town, marrying a daughter of Hon. Daniel Farrand, of Burlington, Vermont. He conducted a flourishing and successful law practice in Plymouth for about twenty years before moving to Concord to take charge of the Herald of Freedom. As student in general literature, especially in history and poetry, none of his day were before him. Few ever heard Shakespeare, Scott, Byron and Burns read more beautifully, more thrillingly, than at his fireside, surrounded by his estimable wife and seven children, with sometimes a few invited friends. But general reading and home delights never detracted from the duties of his profession. When he died, an intimate friend, who had known him long and well, wrote that so accurate was his knowledge of law, and so industrious was he in business, that the success of a client was always confidently expected from the moment his assistance was secured. His life mission, however, was neither literature nor law. He was in due time ordained, consecrated as a high priest in the great fellowship of humanity, and wondrously, divinely did he magnify his office in the ten or twelve last years of his earthly life. In the year 1835, he made acquaintance with Garrison, and soon placed himself at his side as the hated, hunted, persecuted champion of the American slave, as by this time Garrison was known to be. And from that time, too, Rogers was ever found the firm, unshaken, uncompromising friend and advocate of not only the anti-slavery enterprise, but of the causes of temperance, peace, rights of woman, abolition of the gallows and halter, and other social and moral reforms. Here may be the place to say what certainly should be said at some time and place, a few words on the early religious character of Mr. Rogers. For it is neither known to this generation nor presumed what manner of men and women were most of those who early espoused the cause of the American slave; especially in their relations to the popular and prevailing religion of their time. Both Mr. and Mrs. Rogers were active and honored members in the Congregational church at Plymouth, when they espoused the cause of the slave. And they naturally looked, as did other anti-slavery Christians, to the church and pulpit as the divinely appointed instrumentality for emancipating the bondmen, especially of their own country, enslaved, too, by laws of their own enactment and religious sanction and approval. Perhaps a few excerpts from an early editorial in the Herald of Freedom will illustrate the quality of the religious sentiment and opinion of the editor, as well as the tone and temper of his heart and spirit. The whole article is in the Herald of August 11, 1838, and is a review of a contribution to the Christian Examiner, entitled "The Presence of God." The Examiner was a Unitarian journal, the sect at that time quite alien to the more evangelical views of Mr. Rogers: "We wander a moment from our technical anti-slavery sphere, to say, with permission of our readers, a word or two on a beautiful article in the Christian Examiner. It is from the pen of one of our gifted fellow citizens, to whom the unhappy subjects of insanity in this state owe so much for the public charity now contemplated in their behalf. It is written with great eloquence, perspicuity and force of style; and what is more, it seems scarcely to want that spirit of heart-broken Christianity so apt to be missing in the peaceful speculation of reviews, and may we not say in the speculations of the elegant corps among whom the writer of the article is here found. We will find briefly what fault we can with the article. tence of the Eternal Spirit, needs to be broken in upon. We need to help each other to escape a fatuity of mind on this subject that we may feel that God's ark still rides o'er the world's waves, and that the burning bush has not gone out." the entire race of man. It will save only those who will enter it. And the time of entering, as it was at the flood, is before the sky of probation is overcast. The door is that now, as then, before the falling of the first great drops of the eternal thunder shower. Thus loyal was the editor of the Herald to the religious doctrine and teaching of his time in the church of his choice. The church of his fathers through nine generations. Thus diligently had he studied and considered them; and thus eloquently and faithfully, though tenderly and affectionately, did he present, recommend and enforce them, whenever and wherever he had opportunity. In 1838 he removed from Plymouth to Concord, and became sole editor of the Herald of Freedom, He had, from its establishment in 1834, furnished many most brilliant and trenchant articles for its columns. To the readers of the paper, now alas! the most of them, with its editor, no more, nothing need be said of his power with his pen. Only a single duodecimo volume of three hundred and eighty pages of his editorial writings has been reprinted and preserved, and that long ago disappeared from the market. Ten dollars, it is said, have been offered for a single copy; though that perhaps might have been before most of the early readers had passed away. Some of its descriptive articles have been pronounced as unsurpassed in life and vigor, brilliancy and beauty, as were their rebukes of slave holders and their abettors and accomplices, scathing, withering, but always eminently just. His "Jaunt to the White Mountains" with Garrison in the year 1841, was copied from the Herald columns into a neat tract and was a capital contribution to the tourist literature of that period. Its length precludes possibility of insertion here; but one of less volume and of scarcely less power entitled "Ailsa Craig," may not so reasonably be rejected. For the world never knew the sublimely gifted writer as it should have known him, and doubtless would, but for his too early removal to higher spheres. Young readers will surely pardon a page or two when they have read them, introduced here for their profit as well as pleasure, showing not only the power of the writer, but also giving them a description of one of the most remarkable as well as interesting spots in the British realm. It is from the Herald of Freedom of April 30, 1841: This famous rock in the Irish Sea, we meant to have said something about when we saw it, long before this time. But anti-slavery makes us omit and forget the wonders of the Old World. We passed it on a trip from Scotland to Ireland. We left Glasgow on the twenty-eighth of July, 1840, at ten in the morning, for Dublin. William Lloyd Garrison in company, our fellow passenger to the Irish Capital. * * * enclosing mountains which we could descry in the misty distance, up the Vale. "We had supposed it was in the Forth on the other side of Scotland. As we were looking at it, Mr. McTear asked us to guess the distance to it. Strangers he said, were apt to greatly mistake the distance. We looked at the rock along the intervening water. We could get no aid from the shores which were at great distance, quite out of sight on one hand. We supposed of course, we should underrate the distance. So we stretched it liberally, as we thought, and guessed two miles, though it did not look like that distance. the captain. "It will be all the better. It will make quite a flight, ye'll find. Load her up pretty well." The steamer meanwhile kept nearing the giant craig, which was a bare rock from summit to sea, and all of a dull, chalky whiteness, occasioned, as the captain said, by the excrement of the birds. We saw caves in the sides of the mountain and down by the water; the retreats, our informant told us, in former times, of the smugglers who used to frequent the craig and carry on an extensive trade from these places of concealment. We had got so near as to see the white birds flitting across the entrances to the caverns like bees about the hive. With the spy-glass we could see them distinctly and in very considerable numbers; and at length approached so that we could see them on the ledges all over the sides of the mountain. minutes there ensued a general silence. For our own part, we were quite amazed and overawed at the spectacle. We had seen nothing like it before. We had seen White Mountain Notches and Niagara Falls in our own land, and the vastness of the wide and deep ocean, which was separating us from it. We had seen something of art's magnificence in the old world; its cloud-capped towers, gorgeous palaces and solemn temples, but we had never witnessed sublimity to be compared to that rising of sea-birds from Ailsa Craig. They were of countless varieties in kind and size, from the largest goose to the smallest marsh bird, and of every conceivable variety of dismal note. Off they moved in wild and alarmed route, like a people going into exile, filling the air far and wide, with their reproachful lament at the wanton cruelty that had broken them up and driven them into captivity. leaving their native cliffs forever. Slowly and sadly they seemed to return, while the eye sought in vain to ken the outskirts of their mighty caravan. And Ailsa Craig had sunk far into our rear, and quite sensibly diminished in the distance, before the rearmost of the feathered host had disappeared from our sight.

Nor, perhaps, would this cheap age even then understand nor comprehend it.

It quotes Pope and Burns about an "honest man," but seems not to know him when he comes. It celebrated the birthday of [Scottish poet] Robert Burns [1759-1796] with much pomp and demonstration in less than one month after it hung [abolitionist] John Brown [1800-1859] for a heroism and devotion to freedom and humanity, which began, rekindled with divine fervor, where the zeal of LaFayette for a white man's liberty paled out of human sight.

persecuting spirit that burned his illustrious ancestor [the first English Protestant martyr, Rev. John Rogers (1500-1555] in the [1555] Smithfield pyre [under English Queen Mary (1553-1558)]. In the true spirit of martyrdom did Rogers, like John Brown, join the anti-slavery movement in an hour of peril. Garrison had been mobbed in Boston, as was said, "in broad day, by Boston's best men in broadcloth, gentlemen of property and standing"; driven from a female anti-slavery concert of prayer which he had been invited to attend and address. Mr. Garrison said of the spectacle when all the streets near the place of meeting were thronged with a mob burning with murderous intent: "It was an awful, sublime and soul-thrilling scene—enough, one would suppose, to melt adamantine hearts, and make even fiends of darkness stagger and retreat. Indeed the clear, untremulous voice of that Christian heroine, Miss Parker, in prayer occasionally awed the ruffians into silence, and she was heard distinctly, even in the midst of their hisses and yells and curses."Garrison withdrew from the prayer meeting and the mayor entered in obedience to the wishes of the fiendish crew, and dispersed it. Then the cry, the shriek, the yell was, Some of the rioters discovered and seized him. They drew him furiously to a window and were about to thrust him out, when one of them relented and said, But they coiled a rope about his body, nearly stripped him of his clothing, then dragged him through the streets till he was finally rescued by posse comitatus and at frightful peril was at length got to the mayor's office. There he was provided with clothing and from thence sent to jail, as "a disturber of the peace," the mayor and his advisers declaring that "the only way to preserve his life." In Alton Rev. Elijah Parish Lovejoy, too, another anti-slavery editor, had been shot and killed by a mob, five bullets being taken from his body, three from his breast, and that, too, in 1837, only a few months before Mr. Rogers removed with his family to Concord to conduct the Herald of Freedom.

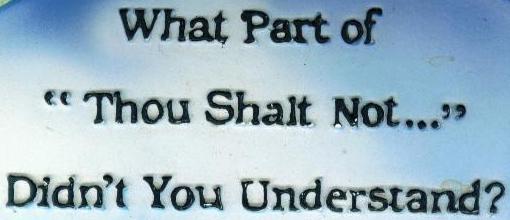

So that in assuming such position, he also, as might be said, "took his life in his hand." For Concord itself was no stranger to the mob at that time and for years afterward was the consecrated guardian of slavery. As a member of the Plymouth Congregational church, both Mr. and Mrs. Rogers had cooperated earnestly, faithfully in works of religious benevolence and charity. But when they demanded that those in bonds in their own country should be remembered even "as bound with them," they were repulsed as disorderly, contumacious disturbers of the peace of the church and its minister, who, at that time, was among the most virulent opposers of the whole anti-slavery enterprise. But they did not withdraw from their church connection till they saw that southern slaveholders were more welcome to the pulpit and sacramental table, than were faithful, devoted abolitionists, whose moral and religious integrity of character, as well as soundness of opinion, were above reproach or suspicion. Rogers, beyond most public men, ever had unshaken faith in the people, though conservative while a politician, and orthodox in his religious faith. When he left the church he investigated its character anew and for himself. The claims of the clergy to prerogative in things temporal as well as spiritual, he soon learned to hold in profound disesteem. To no one man then living, or who has appeared since, does the world owe more than to him for exposing and rebuking the arrogance and insolence not to say down-right fraud and dishonesty, of a ministry whose ruling, directing power in all the great popular demonstrations of the land, north as well as south, was exerted in support and sanctification of slavery. The exceptions to this charge were too few to change the result, as will appear in the progress of this work. Mr. Rogers never doubted for a moment that the people, well and wisely taught, would abolish slavery and cease to oppress one another. And so like the Great Emancipator of Nazareth, he directed all his sternest strokes and rebukes at the priests and rulers, who really "bound the heavy burdens and laid them on men's shoulders [Matthew 23:4]," as in Judea, two thousand years ago. He and his associates of the Garrison school of abolitionists relied solely on the power of moral and spiritual truth to rescue the slave as well as to redeem and save the world. They formed, they joined no political party. They abjured the ballot altogether as a reforming or restoring agency, as much as they did the bullet, the only specie redemption of the ballot, in every government of force. Both Mr. and Mrs. Rogers were members and officers of the New England Non-Resistance Society. And none ever more highly adorned the doctrine of their profession than they. As one with vision anointed to perceive all moral and spiritual truth, Rogers seemed to stand almost alone. His editorial writings are witness to this, and will be to more than the next generation. It were well for man and womankind, if whole volumes of them, judiciously selected, could be reproduced and scattered everywhere, like the shining constellation among the dimmer stars. His words to-day are, many of them, wondrously fresh and new. The temperance cause had no firmer or mure consistent friend. The peace societies had best of reasons to be proud of his support, in word and deed. To him human life was sacred as the life of God. Once, at a grand Peace gathering, it was strenuously argued by most of the members who spoke, that human life could and should be taken by divine command. And the president of the society himself made an argument in defence of all the slaughters of the Canaanites and other tribes and peoples, men, women and children, by Moses, Joshua and their destroying hosts, because perpetrated by command of God. It was at one of the last meetings Rogers ever attended, and he was then too feeble to bear an active part m the deliberations. But after listening a good while to scripture text and learned logic under Levitical law, he rose to his feet and in low voice asked: "Does our brother yonder say that if God commanded him, he would take a sword and use it in slaying human beings, and innocent, helpless human beings? "Yes, if God commanded," was the answer. "Well, I wouldn't," responded Rogers, and sank back into his seat, amid loud cheers of evident approval and admiration. Woman, to him, was in all rights, privileges and prerogatives, the full equal of man. He was a Christian in the divinest, sublimest sense of that still mysterious and much abused word. And as such his kingdom was not of this world. And so he could neither vote in, nor ask others to vote in nor to fight for any government based on military power. As husband and father, none ever knew one in whom his family were more supremely felicitated. As companion and friend, blessed and happy were all those who enjoyed his confidence and esteem. Gentle, simple, tender, kind, ready to sacrifice his own comfort; sharing on occasion, like General Washington, his room and bed with a colored man, and yet always discriminating in high degree; with tastes most refined; ever ready to criticise, even censure a friend, however dear, when he deemed it just and demanded; firm as his own Ailsa Craig, whenever or wherever, or however a moral principal was in jeopardy; running over with music, poetry, and culture of every kind, he was a man, the like of whom the world has seldom seen—may not soon see again. CHAPTER III. SLAVERY—AS IT WAS. Everybody now is anti-slavery. It is honorable now to be a child of the man who "cast the first anti-slavery vote in our town;" or called "our first anti-slavery meeting;" or first entertained Garrison as guest, or Abby Kelley, or Frederick Douglass; or rescued Stephen Foster or Lucy Stone from the hands of a ferocious mob; or raised, or commanded the first company of colored troops in the war of Rebellion, at the time when not a musical band could be found in the whole city of New York to play for a colored regiment, as it marched from the New Haven Railway station to the steamer at the foot of Canal street to embark for the seat of war! "Paid pipers" the venerable Dr. Tyng with withering scorn called them all on the same evening in Cooper Institute, where he presided at a lecture by George William Curtis. "Paid pipers," with wind too immaculate to blow away in escort of a gallant battalion of our country's saviors, "when there was no other name under heaven given among men," whereby the nationality could be saved but the negro name; despised as he was and rejected of men; "a man of sorrows" and acquainted all his dreary life with grief! Everybody now is [claims to be] an abolitionist, or son, or grandson of an anti-slavery parentage, and so all seem to claim equal honor, so far as honor is due, for ridding the world of the sublimest scourge and curse that ever afflicted the human race. Few now, however, have much conception of what slavery was; or what was genuine, effective anti-slavery, when slavery sat supreme "on its throne of skulls," and ruled the whole nation, state, church and school, literature, trade, commerce, manufactures and agriculture, as with rod of iron! And its first command, great command, only command was, "Thou shalt have no god but me." Not, as from Mount Sinai, "no other gods before me," but no other god. Not "no other gods before me," but "no other gods with, or above or below me!" So it was. Anti-slavery then, was more than a name; more than profession; or denomination in religion; or party in the government. So Christianity had mighty meanings when the great apostle to the Gentiles wrote: "I am not ashamed of the gospel of Christ." [Rom 1:16.] And "I determined to know nothing among you save Jesus Christ and him crucified." [I Cor. 2:2.] It had fearful meanings when the gardens of Nero were illumined with the burning bodies of martyred saints, both men and women, young and old! When to name the Christ of God was death in lingering torments—when crucifixions were so multiplied that, as in grim epigram it was said, "space was wanted for crosses, and crosses for christians." And yet so sublime was Christian heroism at that hour, that it could have well been added, but christians are never wanting for crosses. But what was our slave system, that so many now proudly claim to have aided to destroy? And whose fathers and mothers were those who really did bear active, effective part in the thirty years moral and peaceful conflict, inaugurated by Garrison with "sword of the spirit;" whose only weapons were Made mighty through the living God?" Or whose sons and brothers rushed at last to the field of mortal combat, and fought the bloodiest, mightiest, everyway, most frightful war, that has shaken the earth and darkened the skies in all the Christian years? Slavery! What is it? What was it on the American plantation? "Peculiar Institution," some called it. "Patriarchal Institution," others! But what was it? All language pales and is silent in its dread presence. Slave-holding! "Deed without a name!" In cant phrase we said slavery degrades man to the brute, sinks woman to the dead level of the horse. And then who knows the height and depth, the length and breadth of those stunning words; insulting blasphemies against the Holy Spirit of Humanity! Let one advertisement, distributed by large handbills, as well as published in the daily newspapers of New Orleans, aid the imagination :

In the light of a spectacle like this, it is possible to fancy slightly what should be understood when it is said that slavery degrades human beings to the plane of brute beasts. Or reverse the order of illustration, if we dare, and imagine a brute beast raised to the dignity and honor, the privilege and prerogative of a man, an immortal being. History or fable tells us of a Roman Sovereign who made a favorite horse first Consul of the Empire. Such mockery might have been. But suppose in a Christian country, in a Christian sanctuary, it were proposed to admit, not a horse, but some dogs into full fellowship and communion with the church. It is on a delightful Sunday of early summer, in a pleasant New England country town. The village gardens are already abloom with early flowers, the orchards are white with prophecy of abundant fruit, and every tree is an orchestra of cheerful birds, whose worship-notes almost charm the Sabbath silence into sweet accord with the songs of paradise. All the village and the districts around assemble at their, to them, "house of God." At the appointed hour, the baptized communicants of the accepted faith are invited to seats at the sacramental board. The unregenerate of the congregation retire to the outer seats, paying silent but respectful attention. The first scene in the solemn service is admission of new members, who are invited forward to the altar. There, in presence of the congregation, they listen and bow silent assent to the Articles of Faith and the Covenant Vows, and receive the seal of baptism, in the name of the triune God. Solemn and impressive as this may be, it may excite no unusual emotions, being neither new nor infrequent. But slavery, we used to say with lip only, "degrades man and woman to a level with the brutes;" puts the "bay horse, Star," and the "Mulatto girl, Sarah," into the same raffle, or on the same auction-block. Now change the order. Elevate the brutes to the place of immortal beings at the baptismal font and sacramental table. Whistle up two or three dogs and solemnly read over to them the creed and covenant, and sprinkle them with the holy drops of baptism, calling them by their appropriate brute names, "Lion, I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Tiger, I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost." And let the third be a female: "Topsy, I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. Amen." Let such a spectacle be enacted on a delightful summer Sunday afternoon, in a beautiful New England village, in its pleasant white meeting-house, and at the memorial supper of that crucified Redeemer in whom the church and its pastor devoutly believed, and through whom they humbly hoped for salvation. Can the effect on the beholders of such a daring spectacle be described, or even imagined? As well, but no better, attempt a description of that slavery which truly did degrade human beings to a level with horses and with dogs. This whole scene was once supposed as illustration, in the days of slavery, in just such town and house of worship as here described, and not only that town, but the pulpit and religious press of both the hemispheres almost shrieked as with holy horror at what they called so audacious, so diabolical blasphemy. And the cry came up from near and far for immediate punishment of him who had so illumined slavery, to the fullest demand of the statute, which was long confinement, it was held, in the State prison! But one thing was made clear. The words, Slavery degrades man to a level with beasts, were seen and felt as perhaps never before. The congregation where the illustration was presented saw and solemnly felt that from beasts up to men—to men exalted to angelic heights—was no farther than those deeps down which immortal man is plunged, to reach the level of the beasts that perish. And that frightful pit was reached by every chattel slave ever born. But the question, What was American slavery? is not yet answered. To call it robbery, by only our dictionary definition, would pay it high compliment. Its fell [evil, atheist, demonized] work began where all ordinary robbery leaves off.

And if he did not pronounce the slave holder sum of all villains, he did address him in words like these:

Slavery is not robbery therefore, because it is so much more, and worse. Indeed, to rob man of manhood, and beastialize him down with not only animals, but the dead matter on which brutes feed and tread, makes any farther spoliation simply impossible. Or shall we pronounce American slavery adultery, wholesale, unblushing adultery? If not, it must be because, as with robbery, it was something so much worse. For, first, what is adultery but setting aside all rights, privileges and responsibilities, human and divine, of both the marriage and parental relations? Slavery knew no more of marriage and parentage among slaves than among swine. Logically, as well as legally, it could not. And the statutes and court decisions so declared.

The following was the answer:

James G. Birney was at one time a slaveholder as well as judge in the courts, and a ruling elder in the Presbyterian church. He was induced to emancipate his slaves, as well as to provide for their future support, taking them over into the free state of Ohio for that purpose, by the faithful and earnest argument and appeal of Theodore D. Weld, an early, eloquent and everyway most efficient apostle and laborer in the anti-slavery field. Washing his own hands from the blood and guilt of slave holding, Judge Birney set himself to the work of abolishing the foul system. Among his first endeavors was an attempt to purify the churches, beginning with his own. But neither his official standing in both state and church, nor his high consequent social status availed to shield him from every possible indignity and outrage at the hands of infuriated mobs, composed largely sometimes of members of the churches. Driven from Kentucky he removed to Ohio. His descent on Cincinnati, where he had now become known, was a signal to waken all the vengeance of both church and state against him. Meetings were at once called, "to see if the people will permit abolition papers to be published in this city." At the first meeting the postmaster, who was also a minister, presided. A committee of thirteen, all eminent citizens, and eight of them church members, was appointed to wait on Mr. Birney and assure him that his paper must stop, or the meeting would not be responsible for the consequences of its continuance. The chairman of the committee declared that "if the paper were not promptly suspended, a mob, unusual in numbers, determined in purpose, and desolating in its ravages, would be inevitable!" All of which proved true, for the paper did not stop. In the darkness of midnight the mob entered and carried press, types and all else of contents and sunk them in the Ohio river. And twice afterwards was the same outrage perpetrated. No wonder Mr. Burney entitled his memorable tract, published at the time, "The American Churches the Bulwarks of American Slavery." For the title was more than justified on every subsequent page, as will hereafter be made to appear. And the word of divine truth uttered by Mr. Weld, and the baptism of fire and water three times administered by the fiendish mob, with full approval of state, church and pulpit, were sufficient consecration of the author of the memorable tract to his subsequent anti-slavery ministry and apostleship. But returning to the argument. Not only was slavery adultery, as sanctified and committed by the churches, in thus sundering all marriage rights and responsibilities; it was legally and in solemn compact annihilation of human marriage and parentage. The court decisions contained sentiments such as these: "With consent of their masters, slaves may marry; but in a state of slavery it can produce no civil effect, because slaves are deprived of all civil rights." [Judge Matthews of Louisana]. Attorney-General Delany, of Maryland, held that slaves would not be admonished for incontinence, or punished for adultery or fornication; or prosecuted for petty treason, or for killing a husband, being a slave. The code of Louisiana declared, "a slave could not contract matrimony. The association which takes place among slaves, and is called marriage, being properly designated contubernium, a relation without sanctity, and to which no civil rights adhere."So the plain, unquestionable fact was, slavery was wholesale, legalized, sanctified concubinage, or adultery, from first to last. Our government was based on the prostrate bodies, souls, and civil, social, marital, parental, educational, moral and religious rights of half a million of immortal beings. In three-quarters of a century their numbers multiplied till at the downfall of the institution there were four millions, and not one legal marriage ever existed in all their generations! And yet, compelled by law thus to live and herd like brute beasts, hundreds of thousands of them were admitted to baptism and sacramental communion and fellowship in all the great evangelical denominations in the land! One other attribute of the dreadful system remains to be exposed, and that was murder. Under the written law of slavery, more than seventy offences, when committed by slaves, were punishable with death. One law read, "if any slave shall presume to strike any white person, such slave may be lawfully killed." Of course killed on the spot. A woman or girl would have been killed (undoubtedly many were killed) for defending her person against the lustful attack of her overseer or other white assailant. Special laws existed for recapturing escaped slaves at any cost of life to the victims, by first proclaiming them outlaws. The following legal instrument with its accompaniments will suffice to show the way:

-56-

Another advertisement, from the Sumpter County (Alabama) Whig will illustrate the methods of slave hunting in other States besides North Carolina:

The New York Commercial-Advertiser of June 8th, 1827, contained the following item of news, not uncommon at that time, as the irresponsibility of slave-holders over the lives of their slaves had hardly been questioned: "HUNTING MEN WITH DOGS.—A negro who had absconded from his master, and for whom a reward of a hundred dollars was offered, has been apprehended and committed to prison in Savannah." The editor who states the fact adds, with as much coolness as though there were no barbarity in the matter, that he did not surrender till he was considerably maimed by the dogs that had been set on him—desperately fighting them, and badly cutting one of them with a sword. The St. Francisville (La.) Chronicle of February 1st, 1839, reports a slave-hunt after this sort: "Two or three days ago a gentleman of this parish, in hunting runaway negroes, came upon a camp of them in the swamp on Cat Island. He succeeded in arresting two of them, but the third made fight. On being shot in the shoulder, he fled to a sluice, where the dogs succeeded in drowning him before assistance could arrive." Had "assistance arrived," would it have been tendered to the dogs or their victim? is a question, to this day. But calling off the dogs altogether, let the subject be illumined a little farther with lights like this, from the Charleston (S. C.) Courier, in 1825.

True, the killing is here omitted, possibly by accident, but if such an atrocity does not involve murder sublimated, what shall be said of this from the Wilmington (N. C.) Advertiser of July 13th, 1838?

But no more such evidences of the murderous spirit of slavery, can be needed; though the last advertisement suggests an incident in South Carolina, so late as 1844, which is too instructive and assuring not to be given. That "wife, Eliza, who ran away from Colonel Thompson," possibly might have a tale unfolded, whose lightest word would have harrowed up the soul. There were many such tales. A young man in South Carolina was seen walking with a young woman, a slave, to whom it was known he was tenderly attached, and whom, it was farther shown, he married and aided to escape from slavery. That was his crime. He was arrested, tried, and found guilty. Sentence of death was pronounced upon him by Judge J. B. O'Neale, in word and spirit as now reproduced: "JOHN L. BROWN—It is my duty to announce to you the consequences of the conviction which you heard at Winnsboro', and of the opinion you have just heard read, refusing your two-fold motion in arrest of judgment for a new trial. you, I know, most appalling. Little did you dream of it when you stepped into the bar with an air as if you thought it was a fine frolic. But the consequences of crime are just such as you are realizing. Punishment often comes when it is least expected. explain to you until you will be able to understand; and understanding, to call upon the only One who can help you and save you—Jesus Christ, the Lamb of God, who taketh away the sin of the world. To Him I commend you. And through Him may you have that opening of the Day-Spring of mercy from on high, which shall bless you here, and crown you as a saint in an everlasting world, forever and ever. No event in anti-slavery history up to that time so stirred the two hemispheres as did this frightful sentence of Judge O'Neale. Even in the British House of Lords, two illustrious members, Brougham and Denman, gave it pathetic and powerful consideration. One London journal said: "The dreadful case of John L. Brown has created throughout Great Britain, a sensation of deepest and most painful character. Addresses to the churches in South Carolina have been extensively signed by the independent churches in England and Scotland." The Glasgow Argus, among the most important journals of Scotland, twice published the Charge on account of its fearful character, and said of it, "we know of nothing more atrocious in the judicial annals of modern times. * * * And what are we to think of a judge, who in passing sentence for what in our country, our land of Freedom, would be looked upon as a praiseworthy act, invokes the sacred name of Deity and the Holy Book of Inspiration as lending sanction to the atrocity about to be committed!" But perhaps the most imposing movement in Great Britain, on this terrible perversion of all justice, as well as outrage on all decency, humanity and charity, was a "Memorial addressed to the Churches of Christ in South Carolina, as representing those of other states," signed by more than thirteen hundred ministers and office-holders in the churches and other benevolent associations of London, and other portions of the kingdom, in solemn protest against it. But it need hardly be told, that all the sympathy felt, all the effort made, all the appeals and memorials sent, eloquent, tender, pathetic, devout as many, if not all of them were, seemed almost wholly thrown away on the press, pulpit, and vast majority of the people of the United States, even though South Carolina did yield to foreign pressure at last, and commuted the sentence to fifty lashes on the bare back; and even they were said to have been remitted on condition that the young man quit the state forever.

Let then their favorite and faithful poet, [John Greenleaf] Whittier [1807-1892], be their oracle:

-61-

Severity of punishments inflicted on slaves short of death, were often a thousand times more cruel than death by the halter; not unfrequently terminating in death, though only by whipping. But hanging was not always severe enough, as witness a law of Maryland, enacted in 1729: "The slave shall first have the right hand cut off, then be hanged in the usual manner; the head be severed from the body, the body divided into four quarters, and the head and quarters be set up in the most public places of the county where such act was committed."And this horrible barbarity could be inflicted by a simple justice's court. But it may be said this legislation was before the foundations of this republic were laid. That is true. But in the year 1836, in the city of St. Louis, Missouri, an act was perpetrated, of which the following was the accepted newspaper account, on the spot and over the country: On the 28th of April, 1836, in the city of St. Louis, a black man named Mcintosh, who [in attempting self-rescue as per precedents] had stabbed an [extortioner, i.e., felony-committing] officer who had arrested him, The Alton Telegraph thus describes a part of the scene: "All was silent as death while the executioners were piling the wood around the victim. He said not a word till he felt that the flames had seized him. He then uttered an awful howl, attempting to sing and pray, then hung his head and suffered in silence. A St. Louis correspondent of a New York paper sent an account of the diabolical deed, of which this is an excerpt: "The shrieks and groans of the victim were loud and piercing, and to observe one limb after another drop into the fire, was awful indeed. In dying, he was about fifteen minutes. A subsequent Judicial decision by judge Luke E. Lawless, of the Circuit Court of Missouri, made at a session of court in St. Louis, was, that as the burning of Mcintosh was the act, directly or indirectly, by countenance of a majority of the citizens, it is a case which transcends the jurisdiction of the grand jury! And so the dreadful sacrament was sanctified and solemnized by high judicial decision. And as such atrocities were common while slavery lasted, why need the law of Maryland be shorn of its odium and terror in the popular apprehension, only because it was older than the Declaration of American Independence? Assuming that nations are not better than their laws, or that laws are never made till needed, what shall be said of legislation like this? A law of North Carolina provided that: If any person shall wilfully kill his own slave, or of any other person, every such offender shall, on conviction, forfeit and pay the sum of seven hundred pounds, and shall forever be rendered incapable of holding or exercising any office. And this law was not repealed till the year 1821, if ever. Another section of the same act provided: If any person shall, in sudden heat of passion, or by undue correction, kill his own slave, or the slave of any other person, he shall forfeit the sum of three hundred and fifty pounds. A still further provision of the same act read thus: If any person shall wilfully cut out the tongue, put out the eye, castrate, or cruelly scald or burn any slave, or deprive any slave of any limb or member, or shall inflict any other cruel punishment, other than by whipping or beating with a switch, horse-whip or cow-skin, or by putting on irons, or imprisoning such slave, such person, for every such offence, shall forfeit and pay one hundred pounds. Judge Stroud, in his carefully prepared "Sketch of Laws Relating to Slavery," says in his latest edition, (1856): "This, so far as I can learn, has been suffered to disgrace the statute book to the present hour. Amid all the mutations which Christianity has effected within the last century, she has not been able to conquer the spirit which dictated this law." And not to speak of the shameful outrage, so denounced in Deuteronomy, xxiii, i, what must be thought of the decency, humanity, not to say religion, of a people that enacts, supports, sanctifies a law which beats without limit, without mercy, with horse-whip, cowskin or other missile, a human being, man, woman, child, unrebuked, unless the last stroke should produce immediate death? With one more well authenticated fact and one other witness, and he none other than Thomas Jefferson himself, the question as to the character of slavery shall be submitted to readers, to history, to posterity. The outrage to be described was witnessed by John James Appleton, Esq., whom Hon. David Lee Child and his illustrious wife, Mrs. Lydia Maria Child, endorse as "a gentleman of high attainments and accomplishments," a secretary of legation at Rio Janeiro, Madrid and the Hague, commissioner at Naples and charge d'affaires at Stockholm. Mr. Appleton was present at the burial of a female slave in Mississippi, who had been whipped to death by her master, for being gone longer on an errand than was thought necessary. She protested under the terrible torture that she was ill and had to rest in the fields. To complete the climax of horror, she was delivered of a dead child while undergoing the punishment!! Is it strange that she had to rest by the way? But we will hasten to our last witness. To-day as I write, the Democratic party, party of Thomas Jefferson, is celebrating here in Massachusetts, a political success, almost unexampled under the circumstances, in state elections, since the party was first inaugurated. The tribes of Israel never claimed Abraham as their father with more devout pride and filial reverence, than have the Democrats of this nation Thomas Jefferson as theirs, since their party first learned to lisp his name. And those tribes crying, "Crucify Him, crucify Him," in the court-room of Pilate, or mocking their victim as he climbed Mount Calvary, bearing his cross in sweating agony, did not more dishonor their patriarchal father and founder than did the Democratic party and their Whig accomplices on the plains of Texas, murdering the Mexicans in a bloody war to reinstate slavery where the Mexican government, with its Roman Catholic religion, had not many years before, abolished it, as all humanity hoped, forever. That was almost forty years ago. Undoubtedly, devotion to slavery sent the old Whig party to a scarcely too early grave. Worship of the same unclean and bloody Moloch, stove down democratic rule, from the kindled wrath of the Infinite Justice around Fort Sumter, until the victories won yesterday in so many States of this Union, and proudly celebrated to-day, give sign almost unmistakable, of its probable return at the next presidential election. And now the next and last witness as to the whole quality and character of slavery, even as he saw it and himself embraced it, is the patriarchal American Democrat, Thomas Jefferson [1743-1826] himself.

The section relating to slavery contains so many general observations on human relations and obligations, individual as well as collective, social as well as civil and governmental, with a profoundly reverent recognition of higher authority than any man-made institutions, or constitutions, that it surely is not too much to declare that a return of the Democratic party to power will be a blessing or scourge and curse, exactly in proportion as it shall follow, or reject the doctrines and counsels of its justly venerated founder and progenitor, as laid down in the passage from his "Notes on the State of Virginia," here reproduced:

Such was American slavery. Jefferson proved its historian as well as prophet, to wondrous extent. Happy for the nation, had it heeded his wise and timely counsels. Happy for it would it even now learn to regard them. When, before or since our slave system, did governments ever punish with death for seventy offences, and then forbid, under penalties almost as severe as death, to teach one of the victims of such tyranny to read one law of man or God, in any book, the Bible not excepted? It may have been, But when, or where? What but cold-blooded murder must such governing have been! To rid the land of such a plague, no wonder it required an army on our side only, of more than two million seven hundred thousand men, half a million of whom never returned! And then, as a crowning, sealing sacrifice, an idolized president [Ed. Note: Abraham Lincoln] massacred, murdered, and his tall form stretched across their premature graves, while not this nation only, but foreign peoples stood aghast! All this, not to speak of moneyed cost and loss; nor counting the sighs and tears, bereavements and mournings of mothers, sisters, widows and orphans! All this, not reckoning moral and spiritual, as well as financial impoverishment and desolation, not to be restored perhaps till our third and fourth generations! Such was part of the price paid to redeem the land from its uncommon curse. Men called the war of sword and bayonet, Rebellion. It might have been rebellion on the part of slavery and the South. But to the North it was Retribution. The. South claimed as property, the slave. But the North, by the terms of the Federal Union, held him pinned down to the earth as with the point of the bayonet. From the torture-chambers of the imprisoned slave our guilt ascended, by silent but sure evaporation, until it hung in threatening clouds over all the sky, waiting the dread hour when the Infinite Patience could endure it no longer! At last the command was given, and the tempest and thunder shook the very heavens, saying to the North, "Give up;" to the South, "Keep not back." No lightning-rod shielded either; and Slavery, with all its reeking, shrieking altars, and ghastly paraphernalia of whips, fetters, bloodhounds and red-hot branding irons, was swept away in cataclysms of blood and fire! ANTI-SLAVERY — WHAT IT WAS NOT.

Such account could slavery give of itself, "Peculiar Institution " it was often called. But it was not peculiar to the southern states. Fortunes were made by the African slave trade, even in little Rhode Island. The history of slavery and slave trading in Massachusetts is one of the most surprising volumes ever issued by the American press. New Hampshire held slaves.

Vermont, had a fugitive slave case in 1808. But the brave Judge Harrington stunned the remorseless claimant with his decision that "nothing less than a bill of sale from the Almighty could establish ownership" in his victim.